In August of 2017, a major breakthrough occurred when scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detected gravitational waves that were believed to be caused by the collision of two neutron stars. This source, known as GW170817/GRB, was the first gravitational wave (GW) event that was not caused by the merger of two black holes, and was even believed to have led to the formation of one.

As such, scientists from all over the world have been studying this event ever since to learn what they can from it. For example, according to a new study led by the McGill Space Institute and Department of Physics, GW170817/GRB has shown some rather strange behavior since the two neutron stars colliding last August. Instead of dimming, as was expected, it has been gradually growing brighter.

The study that describes the team’s findings, titled “Brightening X-Ray Emission from GW170817/GRB 170817A: Further Evidence for an Outflow“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The study was led by John Ruan of McGill University’s Space Institute and included members from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR), Northwestern University, and the Leicester Institute for Space and Earth Observation.

For the sake of their study, the team relied on data obtained by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, which showed that the remnant has been brightening in the X-ray and radio wavelengths in the months since the collision took place. As Daryl Haggard, an astrophysicist with McGill University whose research group led the new study, said in a recent Chandra press release:

“Usually when we see a short gamma-ray burst, the jet emission generated gets bright for a short time as it smashes into the surrounding medium – then fades as the system stops injecting energy into the outflow. This one is different; it’s definitely not a simple, plain-Jane narrow jet.”

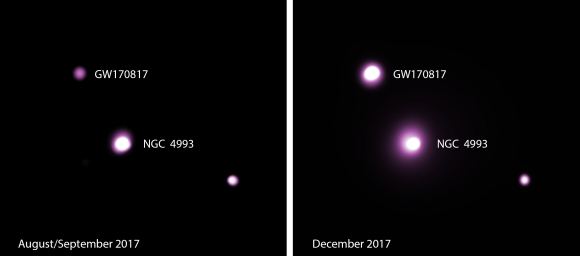

What’s more, these X-ray observations are consistent with radiowave data reported last month by another team of scientists, who also indicated that it was continuing to brighten during the three months since the collision. During this same period, X-ray and optical observatories were unable to monitor GW170817/GRB because it was too close to the Sun at the time.

However, once this period ended, Chandra was able to gather data again, which was consistent with these other observations. As John Ruan explained:

“When the source emerged from that blind spot in the sky in early December, our Chandra team jumped at the chance to see what was going on. Sure enough, the afterglow turned out to be brighter in the X-ray wavelengths, just as it was in the radio.”

This unexpected behavior has led to a serious buzz in the scientific community, with astronomers trying to come up with explanations as to what type of physics could be driving these emissions. One theory is a complex model for neutron star mergers known as “cocoon theory”. In accordance with this theory, the merger of two neutron stars could trigger the release of a jet that shock-heats the surrounding gaseous debris.

This hot “cocoon” around the jet would glow brightly, which would explain the increase in X-ray and radiowave emissions. In the coming months, additional observations are sure to be made for the sake of confirming or denying this explanation. Regardless of whether or not the “cocoon theory” holds up, any and all future studies are sure to reveal a great deal more about this mysterious remnant and its strange behavior.

As Melania Nynka, another McGill postdoctoral researcher and a co-author on the paper indicated, GW170817/GRB presents some truly unique opportunities for astrophysical research. “This neutron-star merger is unlike anything we’ve seen before,” she said. “For astrophysicists, it’s a gift that seems to keep on giving.”

It is no exaggeration to say that the first-ever detection of gravitational waves, which took place in February of 2016, has led to a new era in astronomy. But the detection of two neutron stars colliding was also a revolutionary accomplishment. For the first time, astronomers were able to observe such an event in both light waves and gravitational waves.

In the end, the combination of improved technology, improved methodology, and closer cooperation between institutions and observatories is allowing scientists to study cosmic phenomena that was once merely theoretical. Looking ahead, the possibilities seem almost limitless!

Further Reading: Chandra X-Ray Observatory, The Astrophysical Journal Letters