Following the Moon lately? The up and coming Full Moon is the most famous of them all, as we approach the Harvest Moon for 2018.

Reckoning the Harvest Moon

The Harvest Moon is simple to define, as the Full Moon nearest the the September (southward) equinox, marking the start of astronomical Fall in the northern hemisphere and the start of Spring in the southern hemisphere. With a synodic lunation period (the time it takes the Moon to return to the same phase, i.e. Full to Full, New to New, etc) of 29.5 days, this means that the Harvest Moon usually falls in the month of September, though it very occasionally makes it into early October, bumping the October Hunter’s Moon by a month. This last happened in 2017, and will next occur in 2020. On these years, it also makes the September Full Moon the Full Corn Moon.

Harvest Moon Specifics for 2018

In 2018, the September equinox falls on Sunday, September 23rd at 1:54 Universal Time or 9:54 PM Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) on the evening of Saturday, September 22nd. Of course, this is a mere instant, when the Sun crosses the celestial equator from north to south across the celestial sphere. This always a good time to check out any Stonehenge-esque alignments in your local neighborhood, as the Sun rises due east on the equinox, and sets due west. Many cities and towns, for example, are laid out with streets running along an east-to-west, north-to-south grid.

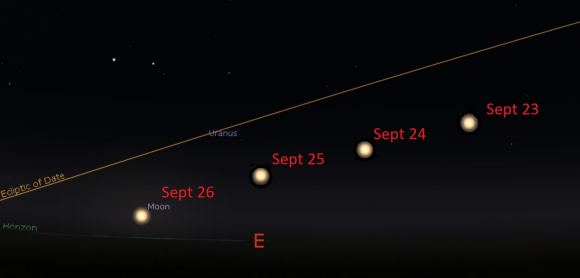

The Moon then follows suit and reaches Full on September 25th at 2:55 UT/10:55 PM EDT(on September 24th), rising very nearly due east as the Sun sets to the west.

Why is the Harvest Moon is special? Back before artificial illumination, the Harvest Moon provided a few extra hours of lighting post sunset, and an opportunity to get the crops in before the onset of winter. But there’s another factor that makes the Harvest Full Moon special for mid-northern latitudes, and that’s its relatively shallow path relative to the local horizon from one night to the next. This all means that the Moon seems to ‘hang’ fixed from one night to the next, losing relatively little time between successive moonrises from night to night.

Here are the rising times versus selected latitudes from one night to the next, right around Full phase for the 2018 Harvest Moon to illustrate this:

| Sept 23 | Sept 24 | Sept 25 | Sept 26 | |

| 30 deg north | 6:55 PM | 7:28 PM | 8:02 PM | 8:36 PM |

| 40 deg north | 7:04 PM | 7:32 PM | 8:02 PM | 8:30 PM |

| 50 deg north | 7:16 PM | 7:39 PM | 8:01 PM | 8:24 PM |

What the Harvest Moon isn’t: Let’s put one common misconception about the Harvest Moon to bed: It isn’t the closest, or largest Full Moon of the year. The Moon actually just passed apogee (its farthest point from the Earth) on September 20 just a few days prior to Full, putting it on the more distant side of things. Sure, the Moon may look a bit larger on the horizon rising than near the zenith thanks to the Ponzo illusion, but it’s actually one Earth radii farther away!

And the sky picture is slowly changing. In the current epoch, the equinoctial point for September falls in the constellation of Virgo, while the March Vernal or northward equinoctial point falls in Pisces. This scene, however, is slowly evolving thanks to the 26,000 year wobble of the axis of the Earth, known appropriately as the Precession of the Equinoxes. This also shifts the two points about 1 degree eastward every 72 years, about the average length of a human life span. Stick around until 2597 AD and the March equinox will pass into the constellation Aquarius, and in 2440 AD the September point will reach the constellation Leo. I doubt we’ll achieve true peace and understanding in the “Age of Aquarius,” though. It is amusing note that while astrologers do embrace precession on this one point, they largely fail to acknowledge it in modern day horoscopes, as the houses should have shifted in the intervening 2,000 years since Ptolemy’s time: most Leos, for example, should be Cancers!

Every lunation of the Moon isn’t the same, either. The Moon’s orbit is tilted 5.145 degrees relative to the ecliptic, otherwise, we’d have two eclipses once every 29.5 days, one lunar and one solar. The orbit of the Moon is also being dragged around the ecliptic once every 18.6 years (mostly due to the gravitational pull of the Sun, known as the precession of the line of apsides). This all means that the apparent path of the Moon goes from ‘shallow’ relative to the ecliptic plane, to ‘ecliptic-like,’ to ‘hilly’ over a two decade cycle. We’re coming off of the shallow years of 2015 right now, and we’re currently headed towards the hilly years of 2025.

The Moon is also one of the easiest objects in the sky to photograph, as it’s a bright, relatively large target. I actually like to try and nab a prospective Moon shot the evening before Full, as you’ll catch it rising against a brighter, low contrast background.

Catching the Moon rising behind a building or landmark takes planning to get positioned just right, and you’ll need to be a good few thousand metres or more away from the target to, say, get a large Moon next to an illuminated foreground structure.

Don’t miss next week’s Harvest Moon.

Read all about the motion of the Moon, eclipses, lunar photography and more in our new book, The Universe Today Ultimate Guide to Viewing the Cosmos, now available for pre-order: