In science, one discovery often leads to more questions and mysteries. That’s certainly true of the ice volcanoes on the dwarf planet Ceres. When the Dawn spacecraft discovered the massive cryovolcano called Ahuna Mons on the surface of Ceres, it led to more questions: How cryovolcanically active is Ceres? And, why do we only see one?

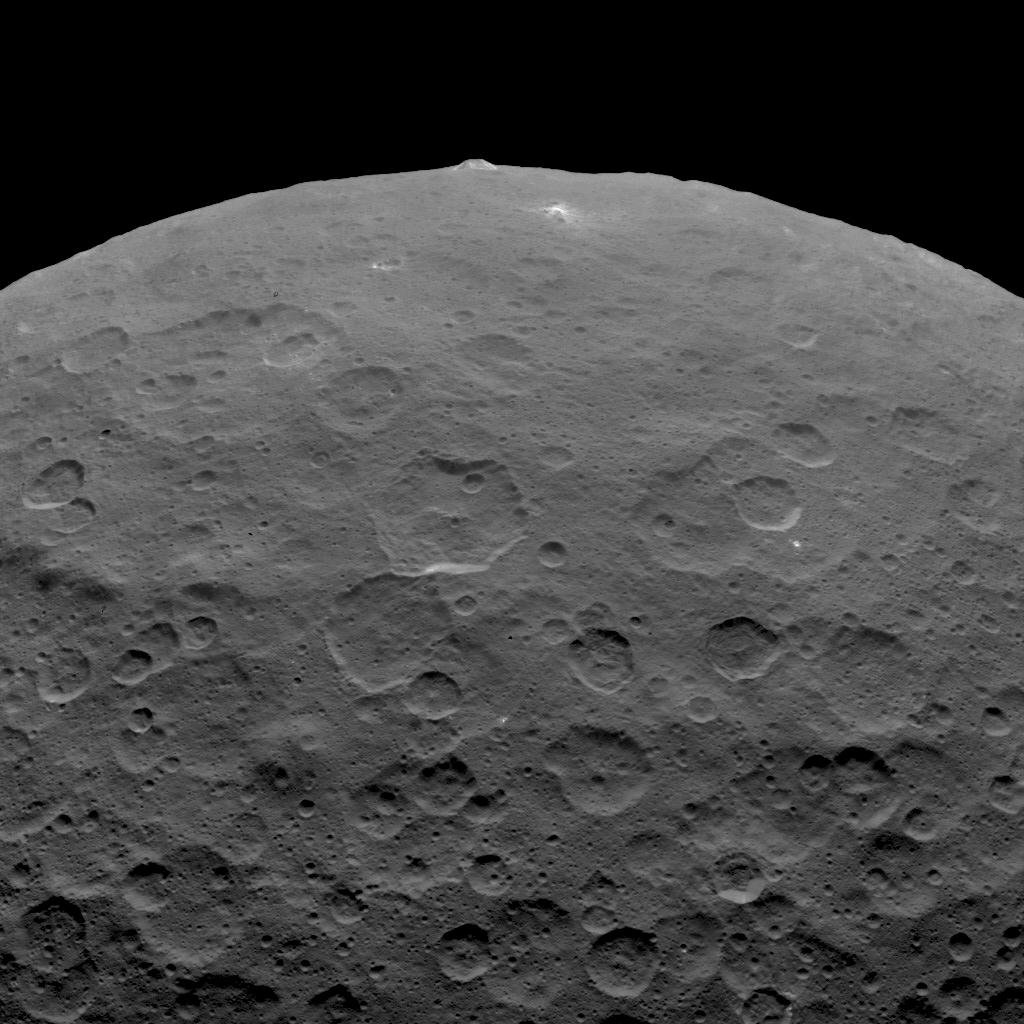

The Dwarf planet Ceres is something special. It’s the only dwarf planet to be examined closely by a spacecraft, and the only cryovolcanically active body to be studied this closely. NASA’s Dawn spacecraft arrived at Ceres in 2015 after visiting the asteroid Vesta. In 2016, NASA scientists revealed the existence of a massive cryovolcano on Ceres called Ahuna Mons.

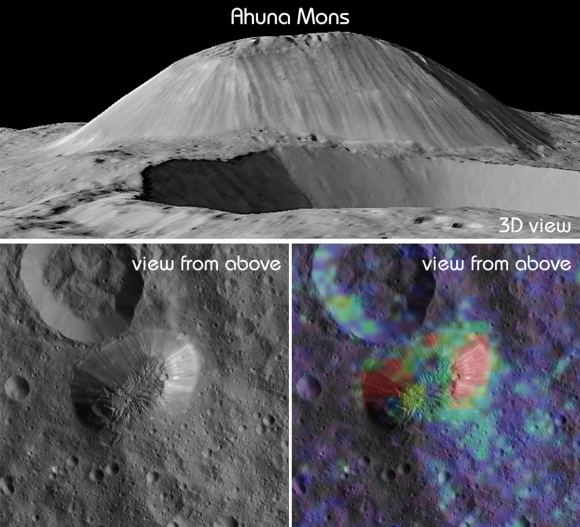

Observations by Dawn revealed something interesting about the 4-kilometer high Ahuna Mons: it’s very young, geologically speaking. It’s only about 200 million years old, whereas Ceres itself is 4.5 billion years old. Though Ahuna Mons is not active anymore, it was active in the recent past. Ahuna Mons’ youthfulness, and the fact that it’s the only ice volcano visible, was a mystery to scientists. It would be very strange for a planet to be dormant for 4.3 billion years, then suddenly erupt in only one place.

There must have been other cryovolcanoes, but where were they?

A study from the University of Arizona (UA), led by UA scientist Michael Sori, helps explain the Ceres ice volcano mystery. Sori and his co-authors from UA, Ali Bramson and Shayne Byrne, discovered that ice volcanoes on Ceres are still actively blasting out enough material to fill a movie theater each year. Their study also explains why we can’t see any remnants of older volcanoes on the surface of Ceres.

According to the paper, any visible evidence of older ice volcanoes is erased by a process known as ‘viscous relaxation.’ A viscous material is something that flows, like water. Thicker fluids like honey and ketchup are also viscous, they just take longer to flow. Ice is also viscous, and here on Earth glaciers are proof of that.

Ceres is mainly rock and ice, so Sori and his team theorized that older volcanoes simply relax into a non-shape, due to the viscosity of their ice/rock makeup. Ice content, and temperature, would determine how quickly they would succumb to viscous relaxation. The higher the ice content, and the higher the temperature, the sooner the ice volcano would disappear.

There are temperature fluctuations on the surface of Ceres, although it never gets warmer than -30 F. The poles stay cold, but temperatures at the equator are more changeable. “Ceres’ poles are cold enough that if you start with a mountain of ice, it doesn’t relax,” Sori said. “But the equator is warm enough that a mountain of ice might relax over geological timescales.”

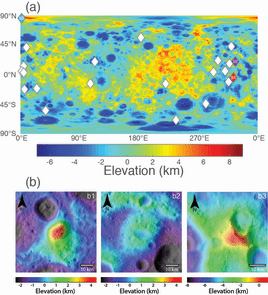

Sori created simulations to test the viscous relaxation theory. In these models, ice volcanoes near the poles stayed frozen forever. But away from the poles, ice volcanoes formed into tall, steep shapes, but slumped into short wide forms over time.

The next step was to scour data from Dawn looking for land forms that matched the simulated ones. Ceres has about 3.4 million square kilometers of surface area, and Sori and his team found 22 mountains that matched those in the simulations.

“The really exciting part that made us think this might be real is that we found only one mountain at the pole.” – Michael Sori, University of Arizona.

“The really exciting part that made us think this might be real is that we found only one mountain at the pole,” Sori said. Yamor Mons is at the pole, and has the same shape as Ahuna Mons. But Yamor Mons is battered with impact craters, which is a testament to its old age. Yamor Mons has not given in to viscous relaxation due to its location at the frigid pole. Yamor Mons is five times wider that it is tall, and other mountains on Ceres conform to the model’s predictions. They are even wider than that.

The team was then able to determine the age of the mountains by comparing them to the models. Using the topography of the mountains, Sori then calculated their volume. The next step was to combine age and volume, and to determine the rate of formation or ice volcanoes on Ceres. “We found that one volcano forms every 50 million years,” Sori said.

From their, the team calculated an average of 13,000 cubic yards of cryovolcanic material each year, which is enough to fill a movie theater, or four Olympic swimming pools.

Compared to Earth’s volcanism that’s not much material. Ceres is much smaller than Earth, and the eruptions are not as violent as terrestrial volcanic eruptions. On Ceres, volcanoes produce cryomagma, a salty mix of rocks, ice and other volatiles such as ammonia. It oozes onto the surface forming the equivalent of a lava dome here on Earth. Over time, these ice volcanoes would simply slump away due to viscous relaxation.

The causes of the ice volcanoes on Ceres are not well-understood. Ceres is the first cryovolcanic body to be studied this closely. Other bodies in the Solar System are likely cryovolcanic, like Europa and Enceladus, but they haven’t been studied closely yet. “There might be similarities between Europa and Ceres, but we need to send the next mission there before we can say for sure,” Sori said.

Sori’s paper was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Sources:

- UA Press Release: “Ceres Takes Life an Ice Volcano at a Time”

- Paper: Cryovolcanic rates on Ceres revealed by topography

- NASA Dawn Mission Overview

- Ceres Wikipedia entry

- NASA Press Release: Ceres’ Geological Activity, Ice Revealed in New Research