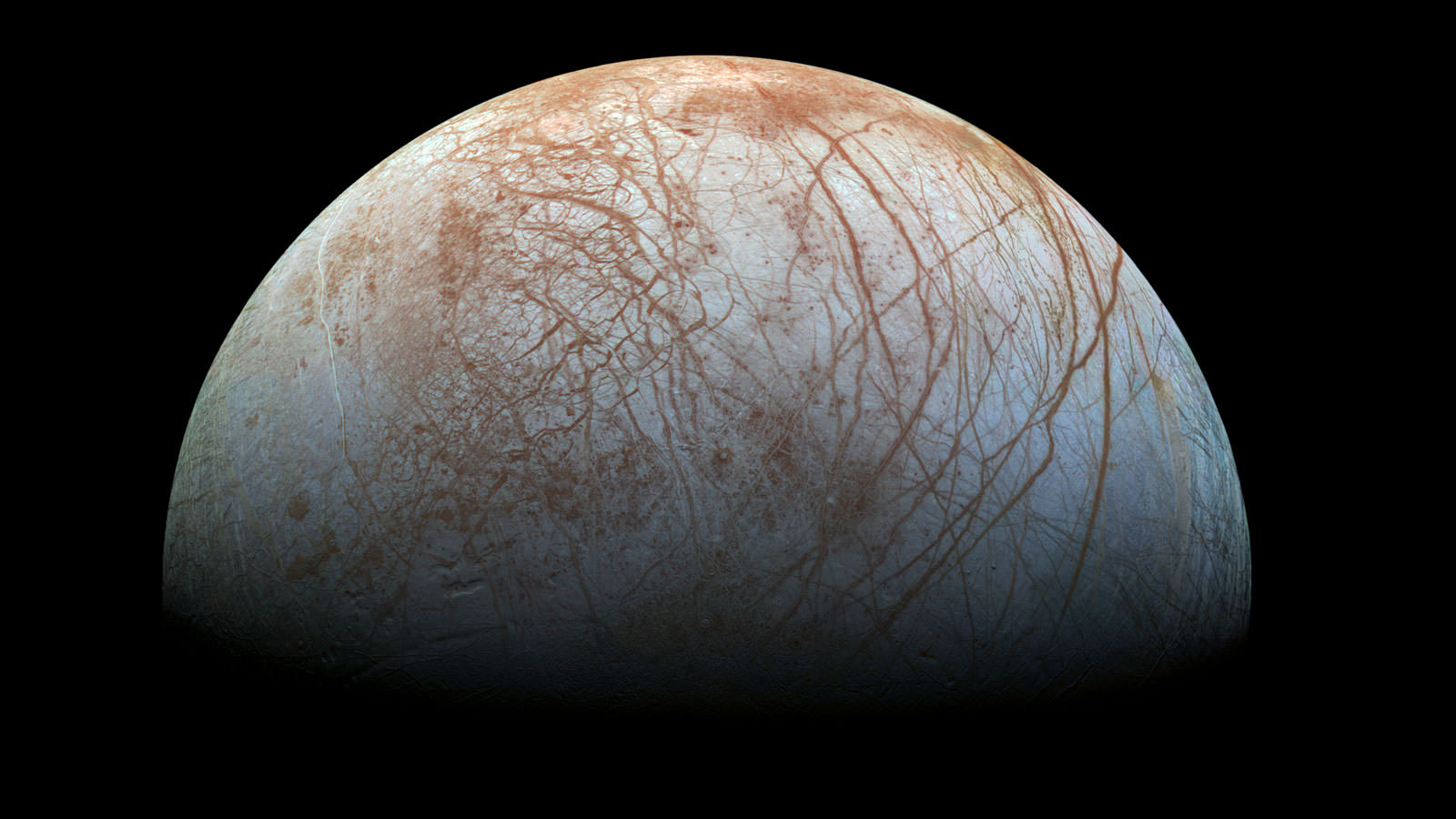

Jupiter’s moon Europa has been the subject of fascination ever since the Pioneer 10 and 11 and Voyager 1 and 2 missions passed through the system back in the 1970s. While the moon has no viable atmosphere and is bombarded by intense radiation from Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field, scientists believe that one of the most likely places to find life beyond Earth exists beneath its icy surface.

Little wonder then why multiple missions are being planned to study this moon up-close. However, if and when those missions reach Europa sometime in the next decade, they will have to contend with some sharp surface features that could make it hard to land. Such is the conclusion of a new study by researchers from Britain, the US and NASA’s Ames Research Center, which indicates that Europa’s surface is covered in bladed terrain.

According to the study, which was recently published by the scientific journal Nature Geosciences, the surface of Europa is likely covered in spikes of ice that measure 15 meters (49 feet) in height. The study was led by Daniel Hobley, a lecturer and research fellow with the School of Earth & Ocean Sciences at Cardiff University.

These features, known as penitentes, are tall sharp-edged spikes made of snow and ice that form through sublimation – the process where rapid changes in temperature cause water to transition from a vapor to a solid (and back again) without changing into a liquid state in between. On Earth, penitentes grow to between 1 and 5 meters ( 3.3 and 16.4 feet) in height, but exist only in high-altitude equatorial regions like the Andes.

On Europa, the process is similar, but conditions are much more ideal for penitentes to form more uniformly across its surface. In addition to having a surface composed largely of water ice, the moon is tidally locked in its rotation with Jupiter. There is also very little variation in the angle in which the Sun shines on the surface, which makes conditions perfect for ice to sublimate without melting.

The New Horizons mission also obtained data during its flyby of Pluto that indicated how these same features form on its surface, especially around the highest altitudes near it’s equator. Because of Pluto’s long orbital period (248 years or 90,560 Earth days), this process takes eons, involves the sublimation of methane ice, and results in penitentes that are about 500 m (1640 ft) high and are spaced about 3-5 km (2-4 mi) apart.

In their study, the researchers used observational data from ground-based radar and thermal observations from the Galileo mission to calculate the sublimation rates at various points on Europa’s surface, then used this to estimate the size and distribution of penitentes. According to their results, the team concluded that penitentes could potentially grow as high as 15 m (49 ft) with a spacing of around 7.5 m (24.6 ft) between each one.

They was also inferred that the penitentes would be more common around Europa’s equator which, as they claim in their study, would explain some of the observations made in the past:

“This interpretation can explain anomalous radar returns seen around Europa’s equator. Penitentes may well explain reduced thermal inertias and positive circular polarization ratios in reflected light from Europa’s equatorial region.”

This could be bad news for missions that are planned to explore Europa for potential signs of life in the next decade. These include NASA’s Europa Clipper (set to launch between 2022 and 2025) and Europa Lander missions (2024), and the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE) – which is set for launch in June 2022.

Whereas both the Europa Clipper and JUICE will be conducting flybys of the planet to determine the presence of biomarkers, the Europa Lander will land directly on the moon’s surface in order to collect information on Europa’s subsurface environment. This would allow scientists to determine how thick the moon’s surface ice is, and perhaps if subsurface lakes exist and where they are located.

One of the most popular targets for exploration is Europa’s southern region, where plumes of water have been detected by the Hubble Space Telescope and other missions. While penitentes may be less common here, and may not reach the same heights as they do around the equator, the presence of such features could make a landed mission very difficult.

As Hobley indicated, this makes Europa a real paradox when it comes to the possibility of near-future exploration. “The unique conditions of Europa present both exciting exploratory possibilities and potentially treacherous danger,” he said.

He’s certainly not exaggerating. This information comes on the heels of another recent study which indicated that Europa and other icy worlds (such as Enceladus) may be too soft to land on. After conducting research that sought to address the negative polarization behavior at low phase angles of icy bodies, the team behind this study concluded that Europa and Enceladus have low-density surfaces that a landed mission would likely sink into.

However, with additional precautions and planning, a suitable mission could still be devised that would be able to ascertain whether or not Europa’s icy shelf has biomarkers on its surface, as well as learn more about its interior environment. And in the meantime, orbiting missions still stand to learn a great deal about this fascinating world.

Jeff Moore – a co-author on the study – noted that NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission could directly observe penitentes with its high-resolution camera and measure other properties of these features with the spacecraft’s other instruments. In addition to being a planetary geologist at NASA’s Ames research Center, Dr. Moore is also a co-investigator on the Europa Clipper mission.

For decades, NASA scientists and other space agencies have been eagerly awaiting the day when a mission to Europa would finally be possible. At this point, there is little that is likely to dissuade those efforts. Neither radiation, nor spikes, nor soft ice appear to be enough to keep us from exploring one of the most likely sources of life beyond Earth!

Further Reading: Cardiff University, Nature Geosciences