The most common type of star in the galaxy is the

red dwarf

star. None of these small, dim stars can be seen from Earth with the naked eye, but they can emit flares far more powerful than anything our Sun emits. Two astronomers using the Hubble space telescope saw a red dwarf star give off a powerful type of flare called a

superflare

. That's bad news for any planets in these stars' so-called habitable zones.

Red dwarfs make up about 75% of the stars in the Milky Way, so they probably host many exoplanets. In fact, scientists think most of the planets that are in habitable zones are orbiting red dwarfs. But the more astronomers observe these stars, the more they're becoming aware of just how chaotic and energetic it can be in their neighbourhoods. That means we might have to re-think what habitable zone means.

"When I realized the sheer amount of light the superflare emitted, I sat looking at my computer screen for quite some time just thinking, 'Whoa.'" - Parke Loyd, Arizona State University.

Two astronomers at the University of Arizona observed young red dwarf stars as part of a program called HAZMAT, or "Habitable Zones and M dwarf Activity across Time". HAZMAT is using the Hubble space telescope to survey red dwarf stars at three different stages of their lives: young, intermediate, and old. HAZMAT focused on the ultraviolet radiation coming from the stars, the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that these stars are most active in. Their results are detailed in a

new paper

.

[caption id="attachment_140308" align="alignnone" width="525"]

An artist's illustration of a red dwarf star. If you could close enough to a red dwarf, it would actually appear orange because of its surface temperature. Image Credit: NASA/Walt FeimerDerivative: - NASA, Public Domain. [/caption]

"Red dwarf stars are the smallest, most common, and longest-lived stars in the galaxy," says Evgenya Shkolnik, an assistant professor in ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration and the HAZMAT program's principal investigator. "In addition, we think that most red dwarf stars have systems of planets orbiting them."

Astronomers think the superflares coming from red dwarf stars are caused by their magnetic fields. Some red dwarf stars are known to have magnetic fields much stronger than larger stars, probably because red dwarfs rotate much faster than larger stars. As the star rotates, its magnetic fields can get tangled. If that tangling gets too intense, the magnetic field lines break and then reconnect, causing a massive flare of ultraviolet energy, a superflare.

The age of the star is part of the superflare phenomena. Younger stars, particularly those in the first one hundred million years of their lives, exhibit more flaring activity than intermediate and old age stars. And it's possible that this flaring occurs daily.

"This means that we're looking at superflares happening every day or even a few times a day." - Parke Loyd, Arizona State University.

Parke Loyd, a post-doctoral researcher at Arizona State University, is the lead author of the paper. He said, "When I realized the sheer amount of light the superflare emitted, I sat looking at my computer screen for quite some time just thinking, 'Whoa.'"

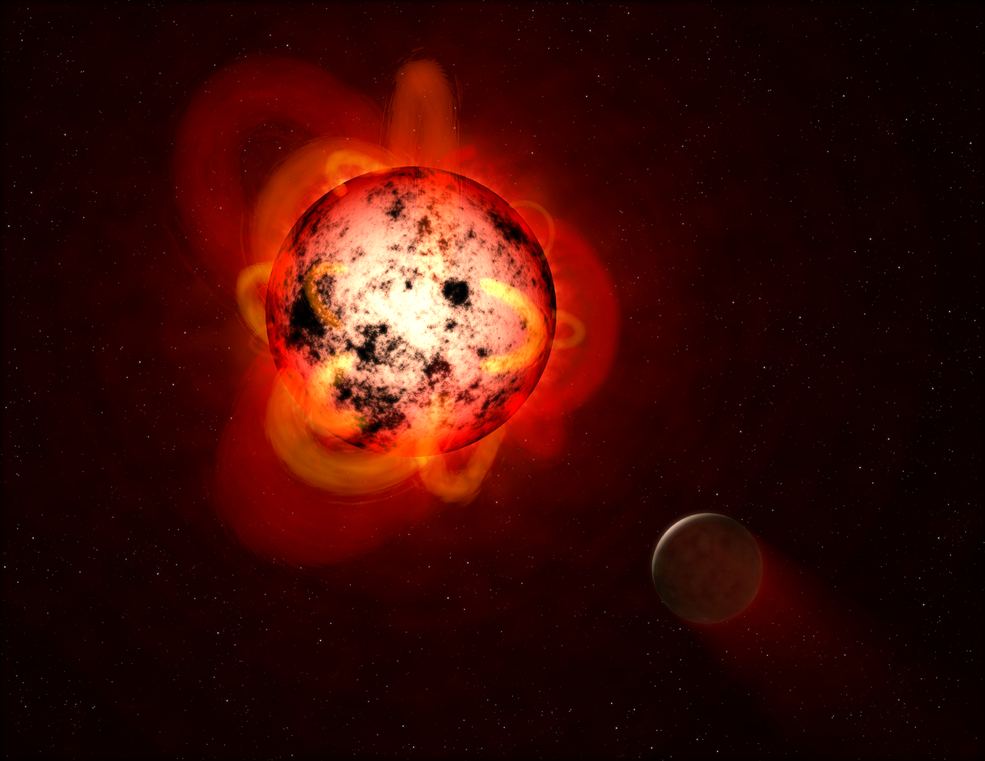

[caption id="attachment_140309" align="alignnone" width="985"]

An artist's illustration of a hypothetical exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf. Image Credit: NASA/ESA/G. Bacon (STScI)[/caption]

"Gathering data on young red dwarfs has been especially important because we suspected these stars would be quite unruly in their youth, which is the first hundred million years or so after they form," Loyd said.

Loyd added, "Most of the potentially-habitable planets in our galaxy have had to withstand intense flares like the ones we observed at some point in their life. That's a sobering thought." The question is, could life survive?

Young red dwarfs emit so much energy, that their superflares are powerful enough to shred the atmosphere of any planets in their habitable zones. Many of these planets might be tidally locked to their red dwarf star, another condition that makes life on these exoplanets a very challenging prospect. But since most habitable zone exoplanets in our galaxy are orbiting red dwarfs, it's important to study the interactions between planet and star.

"The goal of the HAZMAT program is to understand the habitability of planets around low-mass stars," explains Shkolnik. "These low-mass stars are critically important in understanding planetary atmospheres." Ultraviolet radiation can modify the chemistry in a planet's atmosphere, or potentially remove that atmosphere.

"Flares like we observed have the capacity to strip away the atmosphere from a planet. But that doesn't necessarily mean doom and gloom for life on the planet." - Parke Loyd, University of Arizona.

The new study presents data from only the first part of the HAZMAT program. It focused on the flare frequency of young red dwarfs about 40 million years old. These stars are much more energetic and chaotic than their older counterparts. They flare with greater frequency and energy than stars like our own Sun.

In about one hundred years of observing our own Sun, we've witnessed only a couple flares that even approached the energy of the red dwarf superflares. And the two astronomers only observed these red dwarfs for 10 hours. In that time they observed 18 separate flares far more powerful than anything our Sun can produce, with the most powerful one, dubbed the 'Hazflare', 30 times more powerful than anything ever seen with the Hubble.

[caption id="attachment_102362" align="alignnone" width="504"]

In this image, the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) captured an X1.2 class solar flare, peaking on May 15, 2013. Red dwarf superflares can be tens of thousands of times more powerful than these regular types of flares. Credit: NASA/SDO[/caption]

"With the Sun, we have a hundred years of good observations," says Loyd. "And in that time, we've seen one, maybe two, flares that have an energy approaching that of the superflare. In a little less than a day's worth of Hubble observations of these young stars, we caught the superflare. This means that we're looking at superflares happening every day or even a few times a day."

So how would daily superflare activity impact the potential for life on these planets? Loyd is uncertain. "Flares like we observed have the capacity to strip away the atmosphere from a planet. But that doesn't necessarily mean doom and gloom for life on the planet. It just might be different life than we imagine. Or there might be other processes that could replenish the atmosphere of the planet. It's certainly a harsh environment, but I would hesitate to call it a sterile environment."

"I don't think we know for sure one way or another about whether planets orbiting red dwarfs are habitable just yet, but I think time will tell." - Evgenya Shkolnik, Arizona State University.

There may be a silver lining for life on planets orbiting red dwarfs, despite this discovery. One reason that red dwarfs are so dim is that they last a long time. In fact, red dwarfs can exist for trillions of years. This means that exoplanets in the habitable zone of young dwarfs might have a rough start, but their host star's longevity might work in life's favor.

The next part of the HAZMAT program will observe stars in their intermediate age, when it's expected that this flaring activity will calm down. After that stage, HAZMAT will observe red dwarfs in their old age. This will help astronomers understand how red dwarfs and the radiation environment around them and their planets evolves over time. As flaring dies down, the prospects for life might improve.

"They just have many more opportunities for life to evolve, given their longevity," says Shkolnik. "I don't think we know for sure one way or another about whether planets orbiting red dwarfs are habitable just yet, but I think time will tell."

Sources:

- Arizona State University Press Release: " ASU Astronomers Catch Red Dwarf Star in a Superflare Outburst "

- Research Paper: HAZMAT. IV. FLARES AND SUPERFLARES ON YOUNG M STARS IN THE FAR ULTRAVIOLET

- Wikipedia Entry: Red Dwarf

- NASA Press Release: " Superflares From Young Red Dwarf Stars Imperil Planet s"

- NASA Press Release: " Flares May Threaten Planet Habitability Near Red Dwarfs "

Universe Today

Universe Today