Supernovae are the granddaddies of all cosmic light shows, and

Supernova 1987a

is one of the most studied objects in the history of astronomy. As its name makes clear, it was first observed in 1987, and it's the closest supernova observed since the telescope was invented. The 'a' was added to its name because it was the first supernova spotted that year.

SN 1987a is in the Large Magellanic Cloud, about 168,000 light years from Earth. It was first spotted in February of 1987, 160,000 years after it exploded. It's the tumultuous death of a star called Sanduleak -69 202, a blue supergiant. This was a surprise at the time because our stellar models told us that blue supergiant stars couldn't go supernova.

A graduate student with the University of Toronto and the Leiden Observatory has created a time-lapse showing the aftermath of the supernova over a 25-year period, spanning from 1992 to 2017. Her name is Yvette Cendes, and the images show the shockwave expanding outward and slamming into debris that the star shed before it went supernova.

The time-lapse is more than just eye candy for intellectually curious humans. Cendes and her colleagues have published a

paper

in the Astrophysical Journal detailing their results. In their paper, they present evidence that the shockwave from SN 1987a is actually accelerating.

Before a supernova explodes like SN 1987a did, it goes through some death shudders. Its progenitor star,

Sanduleak -69 202

went through both a red and blue supergiant phase. During both these phases, it ejected material which formed outwardly travelling concentric rings around the star. This is called the equatorial ring, and it has inner and outer rings. After the red and blue supergiant phases, the star pauses.

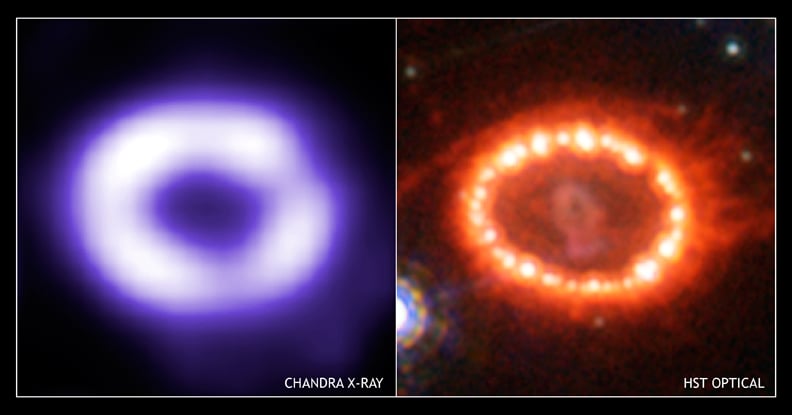

[caption id="attachment_140439" align="alignnone" width="792"]

The expanding ring-shaped remnant of SN 1987A and its interaction with its surroundings, seen in X-ray and visible light. The star that became SN 1987a expelled concentric rings of material during its red and blue supergiant phases, and the shockwave from the supernova lit them up. Image: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=278848[/caption]

After this pause, it eventually goes supernova, and expels material at a much higher velocity than during its previous red and blue supergiant phases. This is called the shock wave. This fast-moving material eventually catches up with the equatorial ring, slamming into it lighting up the rings in a stellar light show.

Cendes and her team present evidence that the supernova shockwave from SN 1987a changes speed as it encounters equatorial rings. They measured the shockwave travelling at 2300 km./sec then accelerating to 3600 km./sec. From this acceleration, they conclude that the shockwave from the supernova is leaving the equatorial rings.

[caption id="attachment_140441" align="alignnone" width="525"]

This image of the supernova remnant SN 1987A was taken by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope in January 2017 using its Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3). Since its launch in 1990 Hubble has observed the expanding dust cloud of SN 1987A several times has helped astronomers get a better understanding of these cosmic explosions. Supernova 1987A is located in the centre of the image amidst a backdrop of stars. The bright ring around the central region of the exploded star is material ejected by the star about 20 000 years before the actual explosion took place. The supernova is surrounded by gaseous clouds. The clouds' red colour represents the glow of hydrogen gas. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, and R. Kirshner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation) and P. Challis (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics)[/caption]

Astronomers are curious about what might happen next with Supernova 1987a. Beyond the equatorial rings is the

circumstellar material

(CSM). It is the material making up the solar wind from the progenitor star, Sanduleak -69 202, before it went through its supergiant phases. Supernova shockwaves are immensely powerful, and they can trigger the birth of new stars when they slam into the CSM. Wouldn't it be cool if humanity could watch that happen in a supernova that has been observed with increasingly sophisticated telescopes as it goes about its business? Yes. Yes it would.

There's still a lot astronomers don't know about blue supergiant stars and how they go supernova. Supernova 1987a is an ongoing observational bonanza for astrophysicists working to unlock the mechanism behind these types of supernovae. We know that supernova "seed" the area around them with heavy elements, and that these materials are likely an important component of terrestrial planets like our dear old Earth. We know that the shockwaves from supernovae slam into surrounding material with such force that it can compress the material and form stars.

So what are we really watching here?

We're watching the ongoing lifecycle of stars in our Universe. The cataclysmic death of Supernova 1987a may very well give birth to new stars. Around these new stars, planets will form. Some of them will be terrestrial in nature, and will contain heavy elements synthesized in SN 1987a's death throes.

On one of those possible terrestrial planets, life might arise. That life might evolve into something intelligent, invent telescopes, and begin to unlock the secrets of the Universe. Far-fetched and overly poetic? Maybe.

In the nuts and bolts of methodical scientific research, what happens next with SN 1987a is immensely interesting. What will happen to the shockwave from the remnant? It's leaving the equatorial ring and will reach the circumstellar material. Will it compress that material and birth new stars?

Keep your eyes peeled for the next several million years and maybe we'll find out.

Sources:

- University of Toronto Press Release: " Timelapse Shows Twenty-five Years In The Life Of One Of The Most Studied Objects In Astronomy: Supernova 1987a "

- Wikipedia Entry: SN 1987A

- Research Paper: " The Re-Acceleration of the Shock Wave in the Radio Remnant of SN 1987A "

- Wikipedia Entry: Supernova

- Wikipedia Entry: Blue Supergiant Star

- NASA web page: " The Dawn of a New Era for Supernova 1987a "

Universe Today

Universe Today