When it comes to meteor showers, the calendar year always seems to save the best for last. We’re referring to the Geminid meteor shower, one of the sure fire bets for dependable meteor showers. In fact, in recent years, the Geminids have been upstaging that other yearly favorite: the August Perseids. If the Geminids did not occur in the chilly (for the northern hemisphere) month of December, they’d most likely get a better rap.

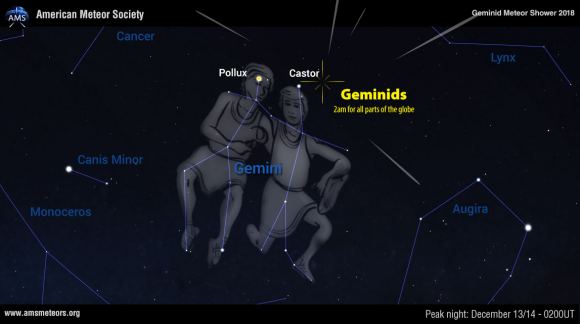

In 2018, the Geminids are expected to peak on the night of Thursday/Friday, December 13/14 with an expected zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) of 100 to 150 meteors an hour centered on December 14th at 2:00 Universal Time (UT). This year sees the Moon at a 45% illuminated, waxing crescent phase on the key evening, meaning it’ll have set by local midnight. The radiant of the Geminids is located at Right Ascension of 7 hours 28 minutes, and a Declination +32 degrees near the bright, +1.9 magnitude star Castor, one half of the twins of Gemini. This also means that the Geminids are well placed from 10 PM local time onwards, as the radiant rises to the northeast.

This shower favors the northern hemisphere, though observers as far as -30 degrees south as latitude (near Cape Town, South Africa) may still manage to catch a low-flying Geminid or two if the shower is particularly intense.

The source of the Geminids is none other than the bizarre ‘rock-comet’ 3200 Phaethon, a six kilometer space rock on a 1.4 year orbit. This path not only intersects the Earth as it sheds the dusty debris that provides us with the annual show that is the December Geminids, but 3200 Phaethon also reaches a perihelion of 0.14 astronomical units (AUs) from the Sun well inside the orbit of Mercury, closer than any other known asteroid. Is 3200 Phaethon a dormant captured cometary nucleus, or some sort of strange transitional object? Clearly, it’s shedding a copious amount of material, as it’s alternately baked, then frozen on its extreme loop around the Sun.

The Geminids were first recognized in 1862, and actually seem to be evolving into a stronger stream in recent years. The 20th century was hit and miss for the Geminids, and they didn’t even crack the top 10 for annual showers until the 1990s. In the early 21st century, however, the Geminids seem to be intensifying, overtaking the Perseids for the top draw spot. Shower streams evolve over time, due to solar wind pressure and the gravitational interplay between the planets. Witness the Andromedid meteors, once the progenitor of some of the greatest meteor storms of the 19th century, which was a fizzled out no-show in 2018.

Here’s what the Geminids have been up to on previous recent years as per the International Meteor Organization’s database:

2017- ZHR = 136 (Moon phase = -11%, waning crescent)

2016- ZHR = 147 (Moon phase = -99%, waning gibbous)

2015- ZHR = 195 (Moon phase = +13%, waxing crescent)

2014- ZHR = 161 (Moon phase = -47%, waning crescent)

2013- ZHR = 165 (Moon phase = +95%, waxing gibbous)

Observing meteors is as easy as finding a site with a good view of the sky, sitting back, and watching. Find as dark a site as possible, and watch off about 45 degrees to either side of the radiant to catch meteors in profile. Keep in mind, the quoted ‘ZHR’ is an idealized rate; light pollution, the true elevation of the zenith and this field of view limits of a single observer all guarantee that you’ll see less than this posted maximum. On the plus side, the peak of the shower spans several days, and it may over-perform expectations if we happen strike a particularly dense and unknown stream. Remember, rates always pick up past local midnight towards dawn, as your observing site turns forward into the oncoming meteor swarm.

Photographing meteors is also pretty straightforward: a wide-field time exposure taken from a tripod-mounted DSLR should easily turn up a meteor trail or two. We like to do simple 30 second to 3 minute exposures, and have them run as an automated series using an intervalometer. This also frees us up to simply sit back and watch the shower, as the camera clicks away. This means you’ll be using the Manual ‘bulb’ setting on the camera. Also, keep a spare battery handy, as time exposures tend to drain power in a hurry, especially on cold December nights. Also, remember to first take a series of exposures at varying ISO and f-stop settings at the beginning, to adjust to the current sky conditions.

And don’t forget to report what you see. The American Meteor Society and the International Meteor Organization both welcome reports of simple counts of meteors by shower from your site… and hey, you’re contributing to real science and our understanding of meteor shower streams and their evolution in the process.

Good luck, stay warm, and happy Geminid hunting!

Read all about observing, photographing and reporting meteor showers in our new book: The Universe Today Ultimate Guide to Observing the Cosmos; on sale now.