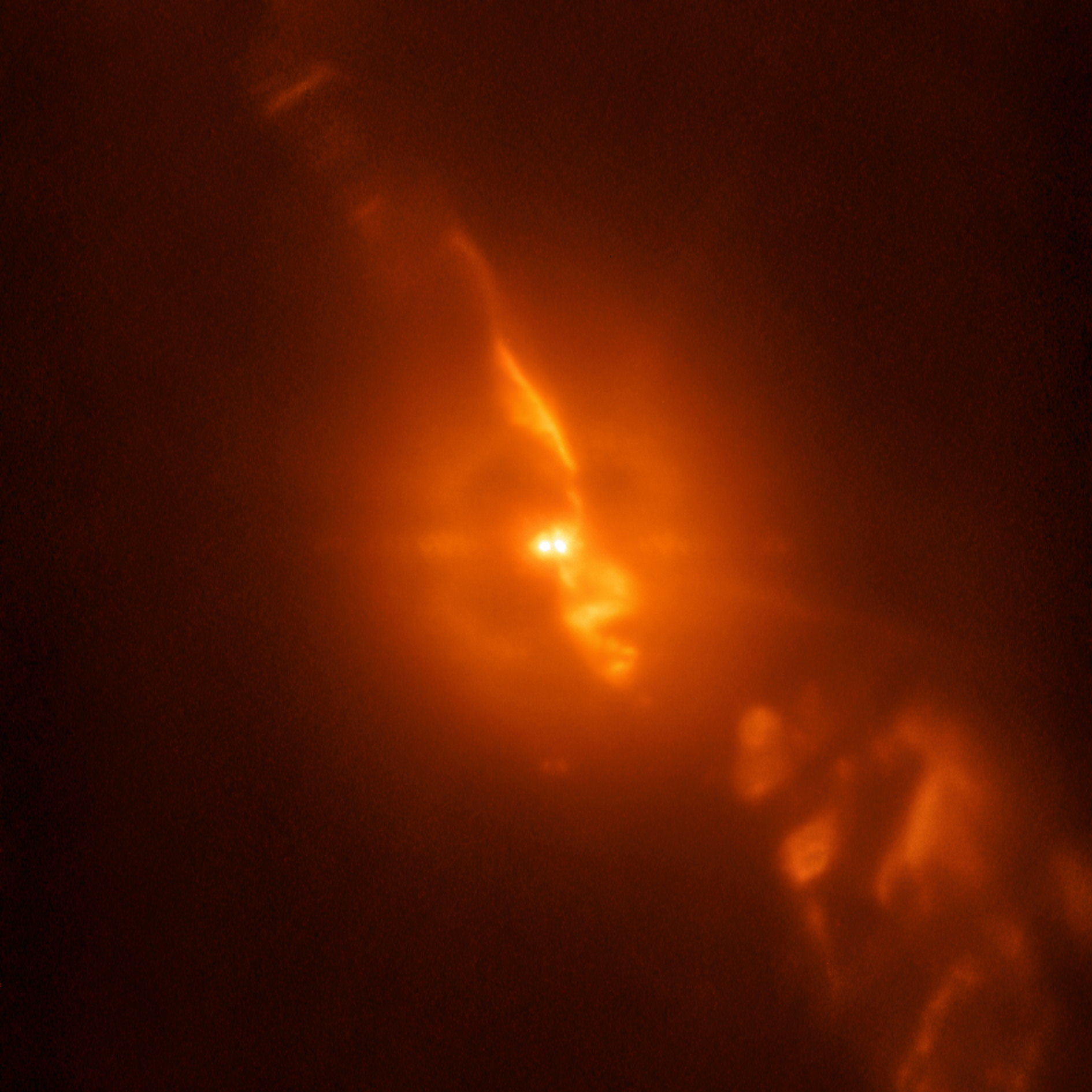

This image is from the SPHERE/ZIMPOL observations of R Aquarii, and shows the binary star itself, with the white dwarf feeding on material from the Mira variable, as well as the jets of material spewing from the stellar couple. Image Credit: ESO/Schmid et al.

The SPHERE planet-hunting instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope captured this image of a white dwarf feeding on its companion star, a type of Red Giant called a Mira variable. Most stars exist in binary systems, and they spend an eternity serenely orbiting their common center of gravity. But something almost sinister is going on between these two.

Astronomers at the ESO have been observing the pair for years and have uncovered what they call a “peculiar story.” The Red Giant is a Mira variable, meaning it’s near the end of its life, and it’s pulsing up to 1,000 times as bright as our Sun. Each time it pulses, its gaseous envelope expands, and the smaller White Dwarf strips material from the Red Giant.

The binary system is called R Aquarii, and it is, of course, in the constellation Aquarius. It’s about 650 light years away from Earth.

If R Aquarii were not a binary system, and was only the red giant, it would still be a dramatic sight. In its death throes, the Mira variable pulses about once every year, and flares up to almost 1,000 times brighter than our Sun. As it pulses, it expands and sheds its outer layers into interstellar space, to be taken up in another generation of starbirth, some time in the future. Its core has run out of hydrogen and fusion has ceased there. Instead, fusion takes place in a shell of hydrogen that surrounds the core.

Left on its own, the Mira variable in R Aquarii would shed its outer layers as a planetary nebula, and in a few million years, would become a white dwarf itself. But its companion has something to say about this.

The Mira variable’s companion in this binary system is a white dwarf. It’s smaller, denser, and much hotter than the Mira variable. It steals stellar material from the Mira star and sucks it in with its gravity. It then sends jets of material out into space.

As if that wasn’t enough for this strange pair, the white dwarf has some fireworks of its own. Sometimes, enough material—mostly hydrogen—from the Mira variable star collects on the surface of the white dwarf, and triggers a thermonuclear nova explosion. The explosion expels more material out into space, adding to the spectacle. The remnants of past nova events can be seen in the tenuous nebula of gas radiating from R Aquarii in this image.

The SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet Research) instrument that captured the main image is a planet-hunting instrument, with the power to directly image exoplanets. But that’s not all it can do. The same power that makes it able to image exoplanets also means it can a wide variety of other astronomical objects, including R. Aquarii.

SPHERE wasn’t the only instrument looking at the odd binary pair. The Hubble has also been looking at the white dwarf feeding on its companion, several times over the years. Below is a three-part image showing how the ‘scopes worked together to understand this system.

How can we explore Saturn’s moon, Enceladus, to include its surface and subsurface ocean, with…

Have you ever wondered how astronomers manage to map out the Milky Way when it's…

NASA astronomers have been continuing to monitor the trajectory of asteroid 2024 YR4. The initial…

Some exoplanets have characteristics totally alien to our Solar System. Hot Jupiters are one such…

Stars form in Giant Molecular Clouds (GMCs), vast clouds of mostly hydrogen that can span…

Let’s dive into one of those cosmic curiosities that's bound to blow your mind: how…