According the Giant Impact Hypothesis, the Earth-Moon system was created roughly 4.5 billion years ago when a Mars-sized object collided with Earth. This impact led to the release of massive amounts of material that eventually coalesced to form the Earth and Moon. Over time, the Moon gradually migrated away from Earth and assumed its current orbit.

Since then, there have been regular exchanges between the Earth and the Moon due to impacts on their surfaces. According to a recent study, an impact that took place during the Hadean Eon (roughly 4 billion years ago) may have been responsible for sending the Earth’s oldest sample of rock to the Moon, where it was retrieved by the Apollo 14 astronauts.

The study, which recently appeared in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters, was led by Jeremy Bellucci from the Swedish Museum of Natural History, and included members from the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI), multiple universities and the Center for Lunar Science and Exploration (CLSE), which is part of NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute.

This discovery was made possible thanks to a new technique developed by the study team for locating impactor fragments in lunar regolith. The development of this technique prompted Dr. David A. Kring – the principle investigator at CLSE and a Universities Space Research Association (USRA) scientist at the LPI – to challenge them to locate a piece of Earth on the Moon.

The resulting investigation led them to find a 2 g (0.07 oz) fragment of rock composed of quartz, feldspar, and zircon. Rocks of this type are commonly found on Earth, but are highly unusual on the Moon. What’s more, a chemical analysis revealed that the rock crystallized in a oxidized system and at temperatures consistent with Earth during the Hadean; rather than the Moon, which was experiencing higher temperatures at the time.

As Dr. Kring indicated in a recent LPI press release:

“It is an extraordinary find that helps paint a better picture of early Earth and the bombardment that modified our planet during the dawn of life.”

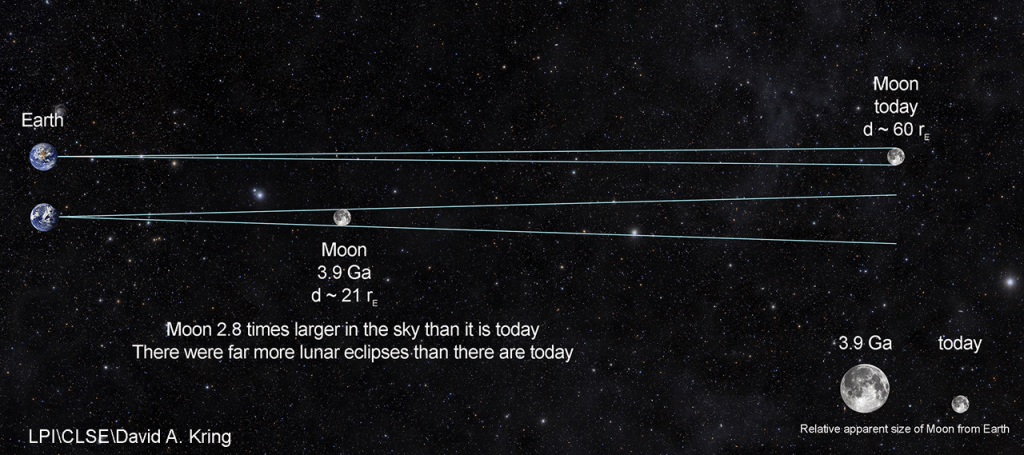

Based on their analysis, the team concluded that the rock was formed in the Hadean Eon and was launched from Earth when a large asteroid or comet impacted the surface. This impact would have jettisoned material into space where it collided with the surface of the Moon, which was three times closer to the Earth at the time. Eventually, this rocky material mixed with lunar regolith to form a single sample.

The team also able to learn a great deal about the sample rock’s history from their analysis. For one, they concluded that the rock crystallized at a depth of about 20 km (12.4 mi) below the Earth’s surface between 4.0. and 4.1 billion years ago, and was then excavated by one or more large impact events that sent it into cis-lunar space.

This is consistent with previous research by the team that showed how impacts during this period – i.e. the Late Heavy Bombardment (which took place roughly 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago) – produced craters thousands of km in diameter, more than enough to eject material from a depth of 20 km (12.4 mi) into space.

They further determined that several other impact events affected it once it reached the lunar surface. One of them caused the sample to partially melt about 3.9 billion years ago, and could have buried it beneath the surface. After that period, the Moon was subjected to impacts that were smaller and less frequent, and gave it the pockmarked surface it has today.

The final impact event that affected this sample occurred about 26 million years ago, during the Paleogene period on Earth. This impact produced the 340 m (1082 ft) diameter Cone Crater and excavated the sample rock back onto the lunar surface. This crater was the landing site of the Apollo 14 mission in 1971, where the mission astronauts obtained rock samples to bring back to Earth for study (which included the Earth rock).

The research team acknowledges that it is possible that the sample could have crystallized on the Moon. However, that would require conditions that have yet to be observed in any lunar samples obtained so far. For instance, the sample would have had to crystallize very deep inside the lunar mantle. Furthermore, the composition of the Moon at those depths is believed to be quite different than what has been observed in the sample rock.

As a result, the simplest explanation is that this is a terrestrial rock that wound up on the Moon, a finding that is likely to generate some controversy. This is inevitable since this is the first Hadean sample of its kind to be found, and site of its discovery is also likely to add to the incredulity factor.

However, Kring anticipates that more samples will be found, as Hadean rocks are likely to have peppered the lunar surface during the Late Heavy Bombardment. Perhaps when crewed missions begin traveling to the Moon in the coming decade, they will chance upon more of the oldest samples of Earth rocks.

The research was made possible thanks to support provided by NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute (SSERVI) as part of a joint venture between the LPI and NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

Further Reading: LPI, Earth and Planetary Science Letters