A new study shows that Mars may very well be volcanically active. Nobody's seen direct evidence of volcanism; no eruptions or magma or anything like that. Rather, the proof is in the water.

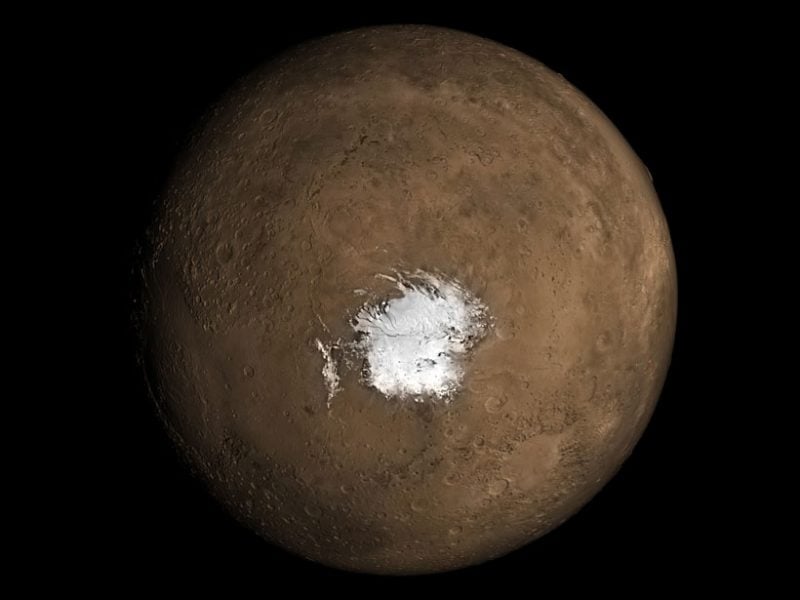

In the past, Mars was a much warmer and wetter place. Now, Mars is still home to lots of water, mostly as vapor and ice. But in August 2018, a study published in Science showed a 20-km-wide lake of liquid water underneath solid ice at the Martian South Pole. The authors of that study suggested that the water was probably kept in liquid state by the pressure from above, and by dissolved salt content.

But this new research shows that pressure and salt couldn't have prevented that water from freezing. Only volcanic activity could have kept it warm enough. Specifically, a magma chamber formed in the last few hundred years is the only way that that water could've been prevented from freezing.

"...we're really interested to see how the community reacts to it."

The 2018 study focused on an area at Mars' south pole called the Planum Australe, or Southern Polar Plain. Radar data from the ESA's Mars Express orbiter. It showed a 20km wide lake of liquid water at what they call the south pole layered deposits (SPLDs). But that study just presented the sub-surface radar data showing the liquid water and suggested that pressure and salt kept the lake from freezing. The authors didn't quantify the conditions required to sustain that liquid water.

The new study, published in the AGU journal Geophysical Research Letters, pours water on the salt and pressure idea. The authors go further, and state that without a magma chamber under the south pole, there is likely no water there at all.

"There could be water there, but you have to explain it, and these guys did a really nice job of saying what is required and that salt is not sufficient."

"Different people may go different ways with this, and we're really interested to see how the community reacts to it," said Michael Sori, an associate staff scientist in the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona and a co-lead author of the new paper.

The debate around water on Mars has been ongoing for a long time. We've confirmed the presence of water, but now the debate is around how much, where, and in what form. And it's not all about whether or not we could somehow use the water on missions to Mars. It's more about understanding how planets form and evolve. It's also about how life might survive on other worlds.

"We think that if there is any life, it likely has to be protected in the subsurface from the radiation."

"We think that if there is any life, it likely has to be protected in the subsurface from the radiation," said Ali Bramson, a postdoctoral research associate at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona and a co-lead author of the new paper. "If there are still magmatic processes active today, maybe they were more common in the recent past, and could supply more widespread basal melting. This could provide a more favorable environment for liquid water and thus, perhaps, life."

Mars and Earth both have giant polar ice sheets. On Earth, it's common for liquid water to persist under ice sheets. Earth is volcanically active, and that heat prevents the sub-surface water from freezing. The 2018 paper drew a parallel between Terrestrial ice sheets and Martian ice sheets, and the liquid water under them, but didn't answer the question of how the water got there.

"We thought there was a lot of room to figure out if [the liquid water] is real, what sort of environment would you need to melt the ice in the first place, what sort of temperatures would you need, what sort of geological process would you need? Because under normal conditions, it should be too cold," Sori said.

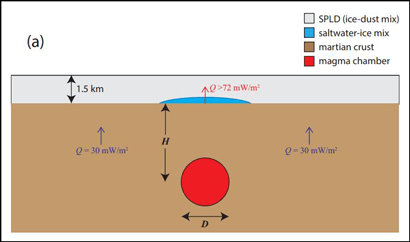

To begin with, Bramson, Sori, and the other authors of the new study assumed that the detection of liquid water under the south pole was correct. Then they figured out what parameters would be necessary to create that water.

They modelled the necessary salt content and the necessary heat flow from the planet to create all that water. They found that salt alone wouldn't be sufficient. They proposed that additional heat would have to be coming from the planet's interior, and the only obvious source of heat would be a magma chamber. (Incidentally, the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Probe on the InSight lander should help answer this question.)

"...it is not just a cold, sort of dead place..."

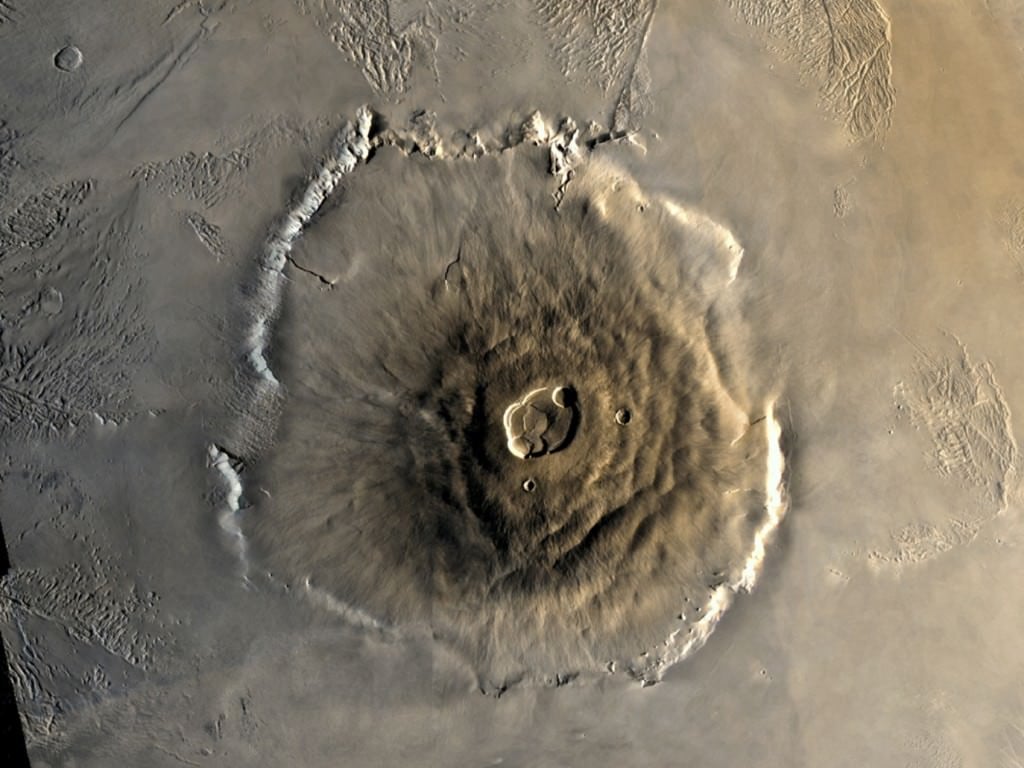

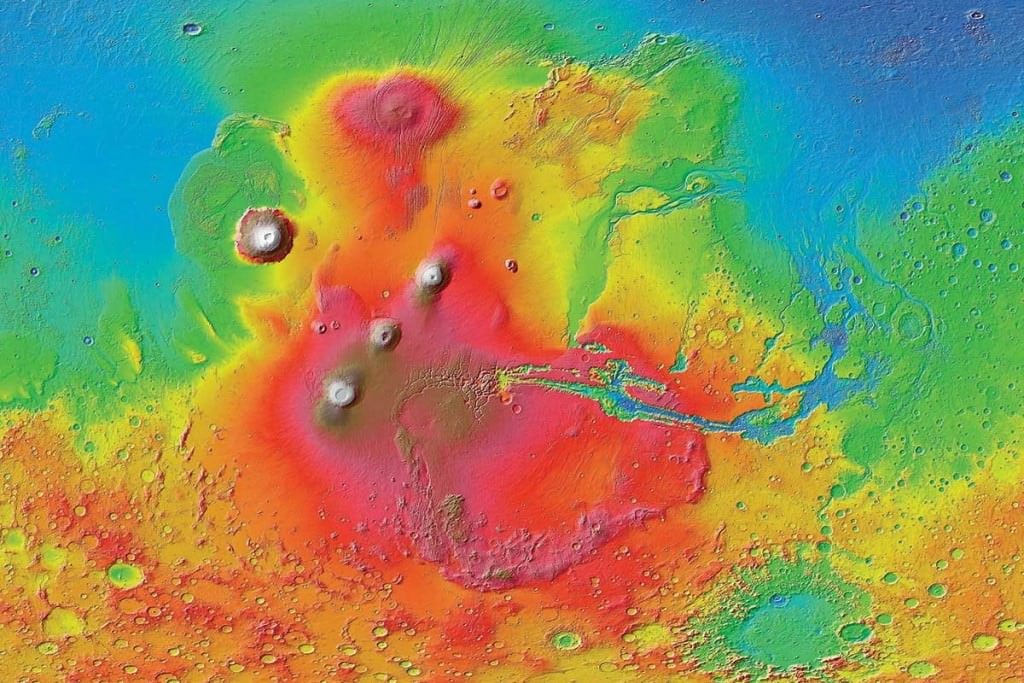

Mars was clearly volcanic in the past. Olympus Mons, a shield volcano on Mars, is the largest volcano in the Solar System, dwarfing anything on Earth. In fact, Mars is home to many volcanoes. There's also Tharsis Montes, a group of three other shield volcanoes near Olympus Mons.

In the paper, the authors argue that about 300,000 years ago, magma from Mars' interior rose to the surface. Rather than break through surface, forming another volcano, it was trapped in a magma chamber under the south pole. The magma chamber would've cooled, releasing enough heat to melt the underside of the polar ice sheet. It would still be there today, slowly releasing heat and preventing the sub-surface lake from freezing.

300,000 years ago isn't that long in geological terms. The authors say that if there was volcanic activity as recently as 300,000 years ago, it could still be happening today.

"This would imply that there is still active magma chamber formation going on in the interior of Mars today and it is not just a cold, sort of dead place, internally," Bramson said.

This new paper definitely places some constraints on the findings in the 2018 paper. The authors don't take a position on whether or not the findings in the 2018 paper are true or not. They just looked at what physical parameters would be required for the water to be there, under the polar ice sheet. In doing so, it adds to the debate, and will likely lead to further study. Hopefully, the InSight lander's heat probe will help us understand the whole issue more clearly.

"I think it was a great idea to do this type of modeling and analysis because you have to explain the water, if it's there, and so it's really a critical piece of the puzzle," said Jack Holt, a professor at the at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, who was not involved in the new research. "The original paper just left it hanging. There could be water there, but you have to explain it, and these guys did a really nice job of saying what is required and that salt is not sufficient."

Universe Today

Universe Today