On December 31st, 2018, the New Horizons probe conducted the first flyby in history of a Kuiper Belt Object (KBO). Roughly half an hour later, the mission controllers were treated to the first clear images of Ultima Thule (aka. 2014 MU69). Over the course of the next two months, the first high-resolution images of the object were released, as well as some rather interesting findings regarding the KBOs shape.

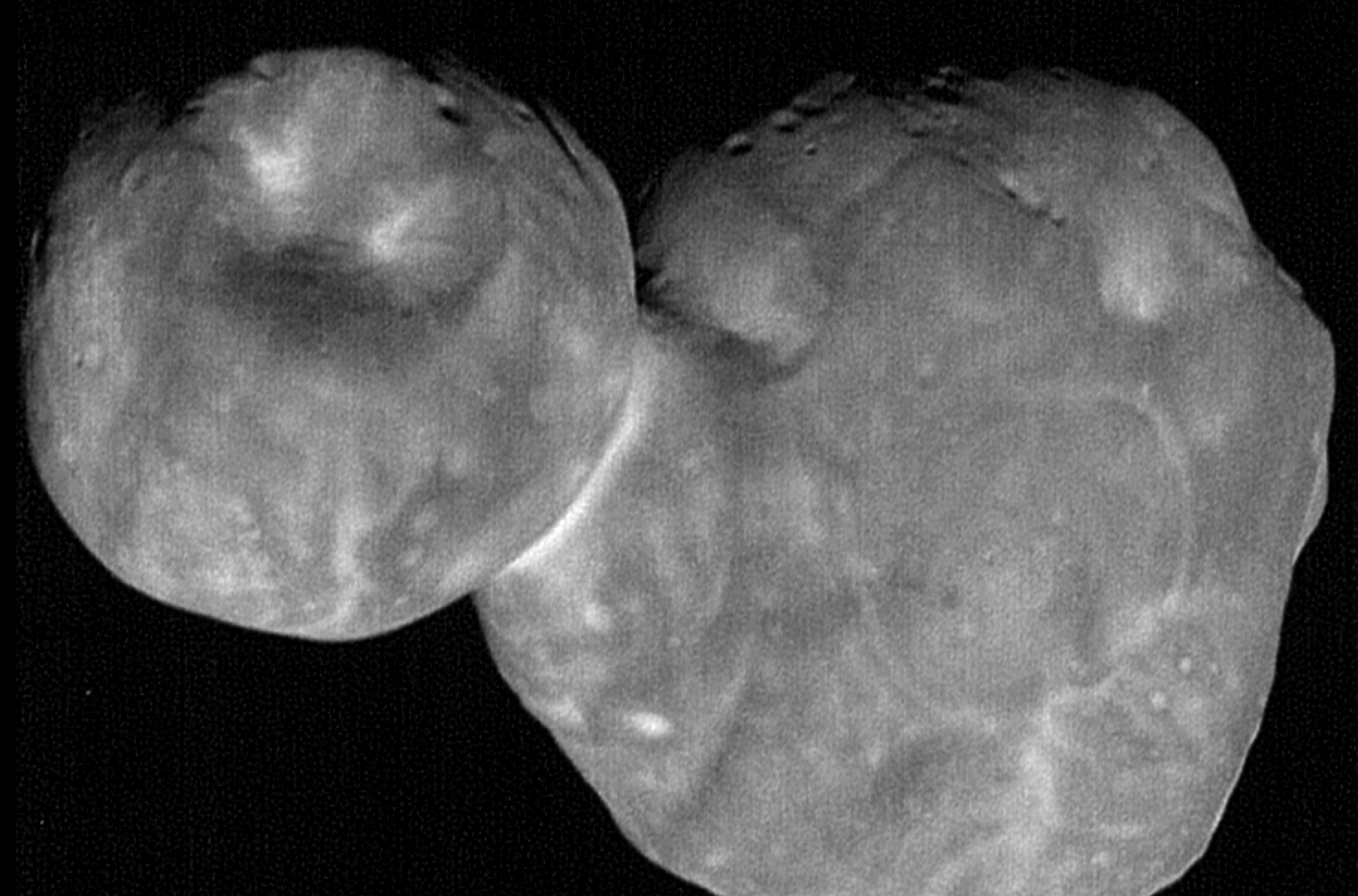

Just recently, NASA released more new images of Ultima Thule, and they are the clearest and most detailed to date! The images were taken as part of what the mission team described as a “stretch goal”, an ambitious objective to take pictures of Ultima Thule mere minutes before the spacecraft made its closest approach. And as you can no doubt tell from the pictures NASA provided, mission accomplished!

The images were all obtained by the New Horizons Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) instrument just six-and-a-half minutes before the spacecraft made its closest approach at 12:33 am EST (09:33 am PST) on Jan. 1st, 2019. The clarity of the images is due to a combination of LORRIs high spatial resolution – 33 m (110 ft) per pixel – and the favorable viewing angle ensured by the New Horizons mission team.

Prior to this latest release, the most-detailed images taken by LORRI were acquired 30 minutes before New Horizons’ closest approach, when the spacecraft was at a range of 28,000 km (18,000 mi) from Ultima Thule. While these provided a detailed look at the object, the latest images are allowing scientists to investigate Ultima Thule’s surface, as well as its origin and evolution.

As Alan Stern, the Principal Investigator of the New Horizons mission at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), indicated in a recent NASA press release, this was no small accomplishment:

“Bullseye! Getting these images required us to know precisely where both tiny Ultima and New Horizons were – moment by moment – as they passed one another at over 32,000 miles per hour in the dim light of the Kuiper Belt, a billion miles beyond Pluto. This was a much tougher observation than anything we had attempted in our 2015 Pluto flyby.”

The clarity of these news images brings out many surface features that weren’t discernible in the previous ones. For example, there are the bright and roughly circular patches of terrain and the many dark pits near the terminator (the line marking the day-night boundary) that are visible now but weren’t before, thanks to the improved resolution.

According to John Spencer, the deputy project scientist from SwRI, the exact cause of these features remains a mystery. At present, the science team is trying to determine if they are the result of impactors, sublimation pits (i.e. surface melting), collapse pits (internal recesses), a combination of these factors, or something else entirely. But with clear image to go by, the mission team is sure to come up with some interesting theories soon.

“These ‘stretch goal’ observations were risky, because there was a real chance we’d only get part or even none of Ultima in the camera’s narrow field of view,” added Stern. “But the science, operations and navigation teams nailed it, and the result is a field day for our science team! Some of the details we now see on Ultima Thule’s surface are unlike any object ever explored before.”

In addition to being the most-detailed images of Ultima Thule to date, these images have the highest spatial resolution of any images taken so far (or perhaps ever) by the New Horizons mission. So says Project Scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, who also noted that the probe’s encounter with the KBO was the most precise flyby ever achieved by a spacecraft.

When New Horizons made its historic flyby of Pluto in 2015 (being the first spacecraft in history to do so), it passed withing 12,500 km (7,750 mi) of the planet’s surface. This allowed the spacecraft to take the first truly detailed images of Pluto’s surface, which highlighted the frozen world’s geological history and the kinds of activity that are still taking place.

But during its flyby of Ultima Thule, the New Horizons spacecraft got approximately three times closer than it did to Pluto – reaching a minimum distance of 3,500 km (2,200 mi). This unprecedented precision was made possible by the ground-based occultation campaigns that were conducted in 2017 and 2018 in Argentina, Senegal, South Africa and Colombia.

The European Space Agency’s Gaia Observatory also provided the locations of the stars that were used during the occultation campaigns to assist in the mission’s navigation. In the coming days, weeks and months, the mission team will be searching through the data obtained by the probe before, during and after its closest approach to find additional clues about the origin and evolution of the first KBO ever encountered.

Of particular interest are whether or not Ultima Thule could have any moonlets or a ring system. Along with detailed images of its surface features, these findings will help scientists to learn more about this particular KBO, not to mention how our Solar System formed billions of years ago and has evolved ever since. And in the coming years, it is hoped that another rendezvous with an ancient object takes place.

While we’re waiting, be sure to check out this video of the new high-resolution images of Ultima Thule taken by New Horizons during its flyby, courtesy of NASA Video and the New Horizons mission team:

Further Reading: NASA

Fantastic photo!

I am left with the impression that the larger mass is probably composed of a cluster of smaller masses, which were subsequently covered with layers of dust accumulated over many millennia.