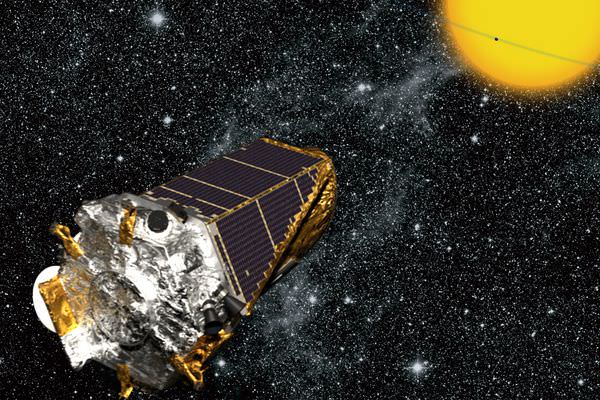

Even though astronomy people are fond of touting the number of exoplanets found by the Kepler spacecraft, those planets aren't actually confirmed. They're more correctly called candidate exoplanets, because the signals that show something's out there, orbiting a distant star, can be caused by something other than exoplanets. It can actually take a long time to confirm their existence.

Science is uber-rigorous, of course, or it should be. We can't have false positives mucking up our data. That's why it took until now to confirm the first exoplanet candidate found by Kepler, known as Kepler 1658 b.

Kepler 1658 b was first discovered by ground-based telescopes before Kepler was even launched. At the time, it was called KOI 4.10, where KOI stands for Kepler Object of Interest. The Kepler mission had already been planned, so they knew that this exoplanet candidate was in Kepler's field of view. And astronomers knew that it would be targeted.

When the Kepler spacecraft was launched, astronomers at first thought that 1658 b was a false positive, meaning that with the data available, they couldn't conclude that it was indeed a planet. That was because the first estimates of the host star were off, way off. They vastly underestimated the mass of the star and the planet. The mass estimates of the planet and the star couldn't explain the effect on the star itself. (Massive planets nudge their host stars gravitationally, and that can be measured.)

So Kepler 1658 b was put on the shelf, to languish as a false positive. Eventually, new software went to work on the Kepler data, and 1658 b was put back into the exoplanet candidate category, awaiting confirmation.

Now, in a new study led by University of Hawaii graduate student Ashley Chontos, 1658 b is confirmed as an exoplanet. But that took some work.

First, Chontos went back through Kepler data looking for targets to reanalyze in 2017. The new analysis made use of stellar sound waves, which is the seismic noise made by a star as it goes about its business of fusion. The study of these waves is called asteroseismology.

The basics of asteroseismology aren't that hard to understand. Larger stars make the lowest, deepest sounds, while smaller stars make high-pitched sounds. It's kind of like modern stereo speakers: sub-woofers are big and make the bass notes, and tweeters are small and make the high notes.

When Chontos analyzed 1658 b's host star, it came out larger than thought.

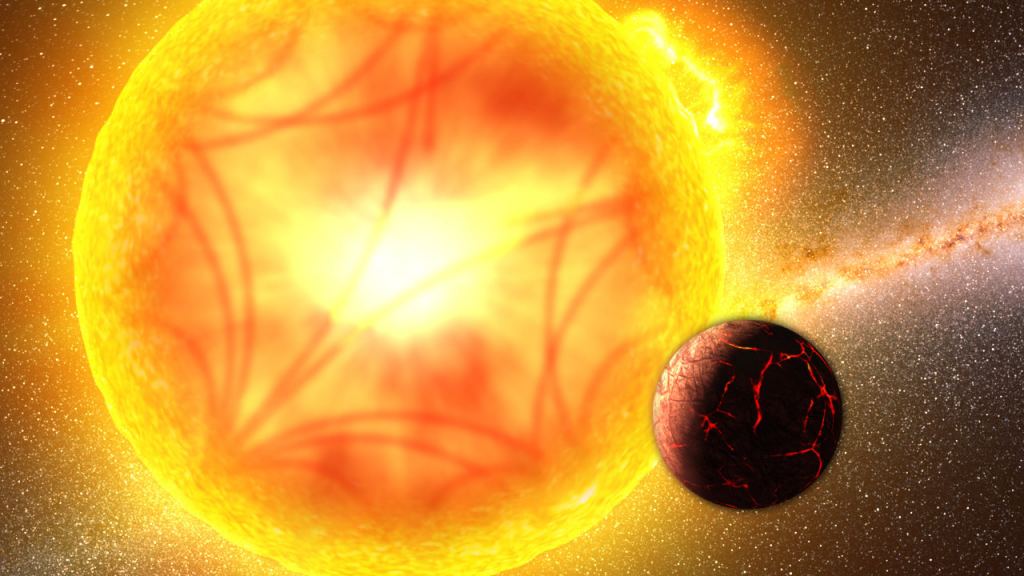

"Our new analysis, which uses stellar sound waves observed in the Kepler data to characterize the star, demonstrated that the star is in fact three times larger than previously thought. This in turn means that the planet is three times larger, revealing that Kepler-1658b is actually a hot Jupiter," Chontos said.

But that wasn't the end. This new analysis suggested that it was an actual planet and not just a false positive. But it still had to be confirmed, and that required more data.

"We alerted Dave Latham (a senior astronomer at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, and co-author on the paper) and his team collected the necessary spectroscopic data to unambiguously show that Kepler-1658b is a planet," said Dan Huber, co-author and astronomer at the University of Hawaii. "As one of the pioneers of exoplanet science and a key figure behind the Kepler mission, it was particularly fitting to have Dave be part of this confirmation."

The new paper is called "The Curious Case of KOI 4: Confirming Kepler's First Exoplanet Detection."

So here are a few facts about exoplanet Kepler 1658 b, and its host star Kepler 1658:

- Kepler 1658 is a massive sub-giant that's currently undergoing a rapid phase of stellar evolution. We only know of nine others like it.

- Kepler 1658 is 50% more massive and three times larger than the Sun.

- Kepler 1658 b is a hot Jupiter, and with an orbital distance of just 0.05 astronomical units, it's one of the closest known planets to a star of this type.

Kepler 1658 is like a future, evolved version of our Sun. Astronomers don't know why yet, but stars like this rarely have planets orbiting them. So the 1658 system is like an extreme case. But its extreme nature allows astronomers to put limits on the complex physical interactions that cause planets to spiral into their host star. This system tells us that this spiralling action happens a lot slower than thought, and so it can't really explain the lack of planets around these stars.

"Kepler-1658 is a perfect example of why a better understanding of host stars of exoplanets is so important," said Chontos. "It also tells us that there are many treasures left to be found in the Kepler data."

Sources:

- Research paper: The Curious Case of KOI 4: Confirming Kepler’s First Exoplanet Detection

- Research paper: TrES-2: The First Transiting Planet in the Kepler Field

- Press Release: Kepler Space Telescope's First Exoplanet Candidate Confirmed, Ten Years After Launch

- Press Release: Discovery Alert! Kepler's First Planet Candidate Confirmed, 10 Years Later

- Press Release: Symphony of stars: The science of stellar sound waves

Universe Today

Universe Today