In February of 2016, scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) made history by announcing the first-ever detection of gravitational waves (GWs). These ripples in the very fabric of the Universe, which are caused by black hole mergers or white dwarfs colliding, were first predicted by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity roughly a century ago.

About a year ago, LIGO’s two facilities were taken offline so its detectors could undergo a series of hardware upgrades. With these upgrades now complete, LIGO recently announced that the observatory will be going back online on April 1st. At that point, its scientists are expecting that its increased sensitivity will allow for “almost daily” detections to take place.

So far, a total of 11 gravitational wave events have been detected over the course of about three and a half years. Ten of these were the result of black hole mergers while the remaining signal was caused by a pair of neutron stars colliding (a kilonova event). By studying these events and others like them, scientists have effectively embarked on a new era of astronomy.

And with the LIGO upgrades now complete, scientists hope to double the number of events that have been detected in the coming year. Said Gabriela González, a professor of physics and astronomy at Louisiana State University who spent years hunting for GWs:

“Galileo invented the telescope or used the telescope for the first time to do astronomy 400 years ago. And today we’re still building better telescopes. I think this decade has been the beginning of gravitational wave astronomy. So this will keep making progress, with better detectors, with different detectors, with more detectors.”

Located in Hanfrod, Washington, and Livingston, Louisiana, the two LIGO detectors consist of two concrete pipes that are joined at the base (forming a giant L-shape) and extend perpendicular to each other for about 3.2 km (2 mi). Inside the pipelines, two powerful laser beams that are bounced off a series of mirrors are used to measure the length of each arm with extreme precision.

As gravitational waves pass through the detectors, they distort space and cause the length to change by the tiniest of distances (i.e. at the subatomic level). According to Joseph Giaime, the head of the LIGO Observatory in Livingston, Louisiana, the recent upgrades include optics that will boost laser power and reduce “noise” in their measurements.

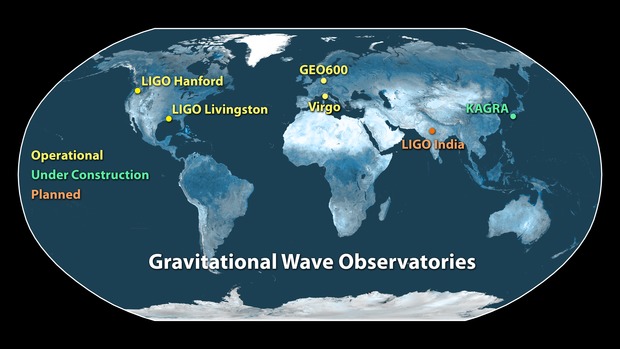

For the remainder of the year, research into gravitational waves will also be bolstered by the fact that a third detector (the Virgo Interferometer in Italy) will also be conducting observations. During LIGO’s last observation run, which lasted from November 2016 to August 2017, Virgo was only operational and able to offer support for the very end of it.

In addition, Japan’s KAGRA observatory is expected to go online in the near future, allowing for an even more robust detection network. In the end, having multiple observatories separated by vast distances around the world not only allows for a greater degree of confirmation, but also helps narrow down the possible locations of GW sources.

For the next observation run, GW astronomers will also have the benefit of a public alert system – which has become a regular feature of modern astronomy. Basically, when LIGO detects a GW event, the team will send out an alert so that observatories around the world can point their telescopes to the source – in case the event produces observable phenomena.

This was certainly the case with the kilnova event that took place in 2017 (also known as GW170817). After the two neutron stars that produced the GWs collided, a bright afterglow resulted that actually grew brighter over time. The collision also led to the release of superfast jets of material and the formation of a black hole.

According to Nergis Mavalvala, a gravitational wave researcher at MIT, observable phenomena that are related to GW events have been a rare treat so far. In addition, there’s always the chance that something completely unexpected will be spotted that will leave scientists baffled and astounded:

“We’ve only seen this handful of black holes out of all the possible ones that are out there. There are many, many questions we still don’t know how to answer… That’s how discovery happens. You turn on a new instrument, you point it out at the sky, and you see something that you had no idea existed.”

Gravitational wave research is merely one of several revolutions taking place in astronomy these days. And much like the other fields of research (like exoplanet studies and observations of the early Universe), it stands to benefit from the introduction of both improved instruments and methods in the coming years.

Further Reading: NPR