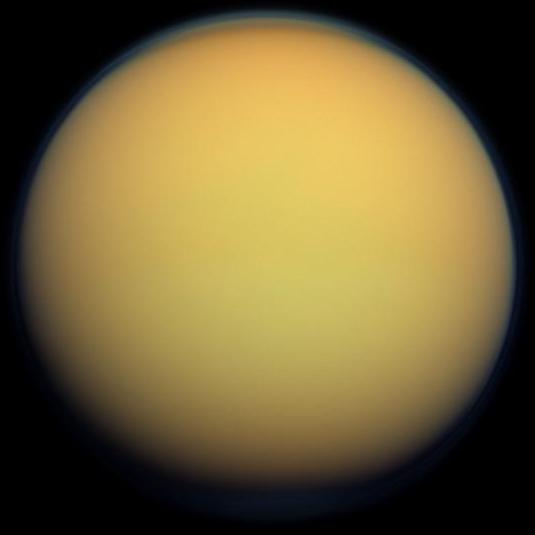

For people interested in all things beyond Earth, the words methane and Titan go hand in hand. After all, Titan is the only other world in our Solar System where liquid flows over the surface. While trying to understand Titan's methane cycle, scientists have discovered something else: a bizarre methane ice feature that wraps halfway around Saturn's largest moon.

There's a lot of mystery surrounding Titan, and especially around its methane cycle. Most of what we know about the moon is a result of the Cassini mission. That mission ended in September 2017, but the data is still being studied.

On Titan, methane in the atmosphere is continually broken apart by the Sun's energy. That creates a haze in the atmosphere, which settles to the surface as organic sediments. The thing is, there's no clear source for new methane, so Titan is being depleted of methane in geological time scales.

A team of researchers led by Caitlin Griffith of the University of Arizona were trying to understand the moon's methane cycle. The only obvious source for new methane is the liquid methane lakes and seas on the surface, though they will be depleted eventually. Griffith and her team were interested in potential cryovolcanoes that might exist on the surface of Titan, and if they signalled the presence of subsurface reservoirs of methane.

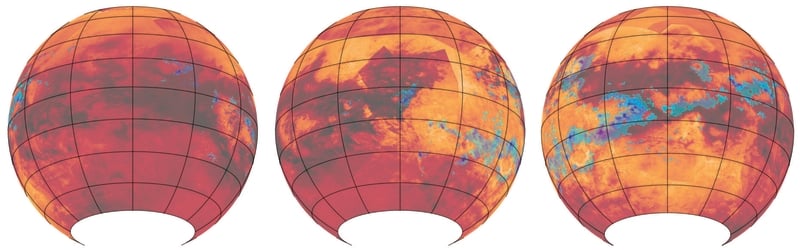

However, the team discovered something unexpected: a linear corridor of methane ice and bedrock that spanned 40% of Titan's surface.

"This icy corridor is puzzling, because it doesn't correlate with any surface features nor measurements of the subsurface," Griffith said. "Given that our study and past work indicate that Titan is currently not volcanically active, the trace of the corridor is likely a vestige of the past. We detect this feature on steep slopes, but not on all slopes. This suggests that the icy corridor is currently eroding, potentially unveiling presence of ice and organic strata."

The team analyzed tens of thousands of images captured by Cassini's

Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer. Titan is difficult to observe because of its thick, hazy atmosphere, but Griffith and the other scientists behind the study used a new method to tease out the detail of some surface features. They were actually looking for interesting organic materials that accumulate on the surface as a result of the Sun breaking up the atmospheric methane.

Of course it wouldn't be science if they didn't try to test or validate their own results. They compared their results with what the tiny Huygens probe saw, when it was sent to the surface of Titan by the Cassini spacecraft. The comparison did indeed validate their results.

"Both Titan and Earth followed different evolutionary paths, and both ended up with unique organic-rich atmospheres and surfaces," Griffth said. "But it is not clear whether Titan and Earth are common blueprints of the organic-rich of bodies or two among many possible organic-rich worlds."

As with all things Titan, these results are both compelling and mysterious, and seem to answer questions as well as pose new ones.

These results are a bit of a side-track of the team's goal. They still want to study the diverse organic sediments that accumulate on the surface as a result of the photolysis of the atmospheric methane. They're hopeful that the technique they used can also be used in that endeavour.

Sources:

- Press Release: Researchers Find Ice Feature on Saturn’s Giant Moon

- Research paper: A corridor of exposed ice-rich bedrock across Titan’s tropical region

Universe Today

Universe Today