According to a new NASA-funded study that appeared in Astrobiology, the next missions to Mars should be on the lookout for rocks that look like “fettuccine”. The reason for this, according to the research team, is that the formation of these types of rocks is controlled by a form of ancient and hardy bacteria here on Earth that are able to thrive in conditions similar to what Mars experiences today.

This bacteria is known as Sulfurihydrogenibium

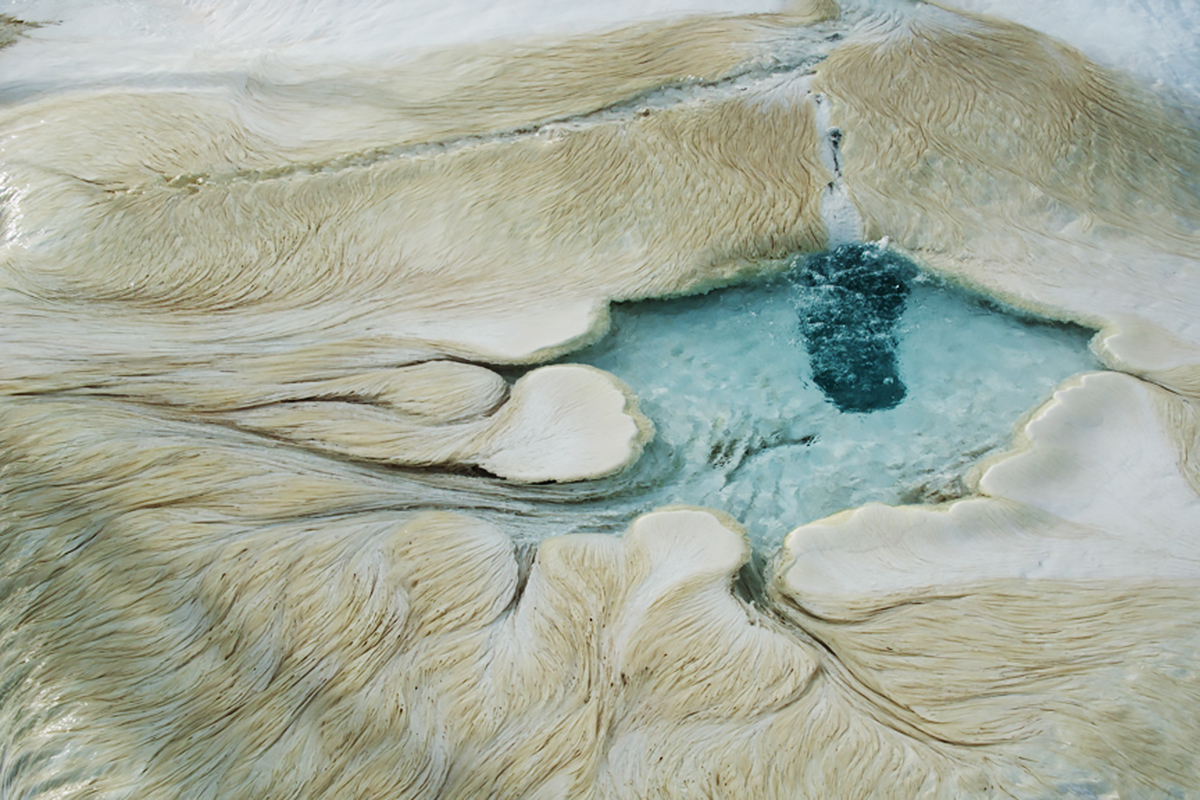

In hot springs, the microbe assembles itself into strands and promotes the crystallization of calcium carbonate rock (aka. travertine), which is what gives it its “pasta-like” appearance. This behavior makes it relatively easy to detect when conducting geological surveys and would make it easy to identify when searching for signs of life on other planets.

Bruce Fouke, a professor of geology and an affiliate professor with the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology (IGB) at the University of Illinois, was also the lead researcher on the study. “It has an unusual name, Sulfurihydrogenibium

The unique-shape and structure of these strands are the result of the environment this bacteria evolved to survive in. Given that they inhabit fast-flowing water, the

“They form tightly wound cables that wave like a flag that is fixed on one end. The waving cables keep other microbes from attaching. Sulfuri also defends itself by oozing a slippery mucus. These Sulfuri cables look amazingly like fettuccine pasta, while further downstream they look more like capellini pasta.”

To analyze the bacteria, the researchers collecting samples from Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park, using sterilized pasta forks (of all things!) The team then studies the microbial genomes to evaluate which genes were being actively transplanted into proteins, which allowed them to discern the organism’s metabolic needs.

The team also examined the bacteria’s rock-building capabilities and found that proteins on the bacterial surface dramatically increase the rate at which calcium carbonate crystallizes in and around the strands. In fact, they determined that these proteins cause crystallization at a rate that is one billion times faster than in any other natural environment on the planet.

As Fouke indicated, this type of bacteria and the resulting rock formations are something Mars rovers should be on the lookout for, as they would be an easily-discernible biosignature:

“This should be an easy form of fossilized life for a rover to detect on other planets. If we see the deposition of this kind of extensive filamentous rock on other planets, we would know it’s a fingerprint of life. It’s big and it’s unique. No other rocks look like this. It would be definitive evidence of the presences of alien microbes.”

A little over a year from now, NASA’s Mars 2020 rover will be heading to the Red Planet to carry on in the hunt for life. One of the rover’s main objectives will be to collect samples and leave them in a cache for eventual return to Earth. If the rover does come across formations of mineral strands where hot springs were once thought to exist, it is entirely possible that they will contain the fossilized remains of bacteria.

Needless to say, a sample of that would be invaluable, as it would prove that Earth is not unique in having brought forth life. Be sure to check out this video of the team’s field research in Yellowstone National Park, courtesy of Institute for Genomic Biology (IGB) Illinois:

Further Reading: Illinois News Bureau, Astrobiology

Interesting. The only other bacterial fossil not needing microscale chemical analysis for exclusion of false positives is AFAIK not stromatolite formations as one could think. But etched pores in volcanic glasses, which has no mineral formation confounds.