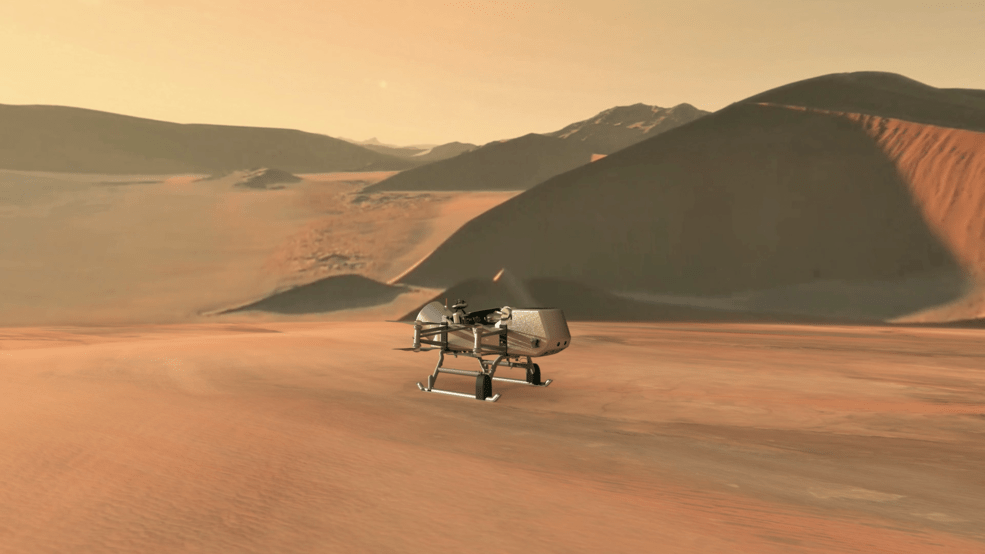

The official announcement has been made. NASA is sending the Dragonfly, its rotary-winged flying robot, to Titan. We'll have to control our excitement for a while, though. The launch date isn't until 2026.

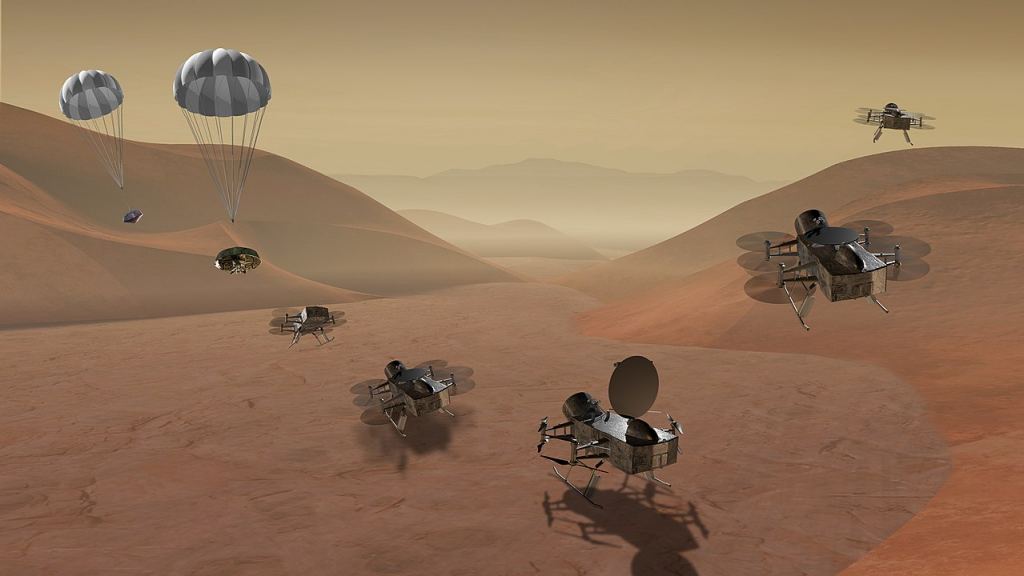

The Dragonfly is a technological marvel. It'll have 8 rotors that operate in 4 pairs, and it'll be powered by a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG). During the day, the robot will fly by battery power, and at night the MMRTG will recharge its batteries. The design has been on the drawing board for a while, and we've been expecting this announcement.

“Titan is unlike any other place in the solar system, and Dragonfly is like no other mission.” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s Associate Administrator for Science

The Dragonfly is uniquely suited to explore this bizarre world. It'll be able to fly through Titan's dense atmosphere, which is almost 4 times as dense as Earth's. It'll fly to multiple locations on Titan to gather data. During it's projected mission length of 2.7 years, Dragonfly will eventually travel more than 175 km (108 miles). That means it will travel more than double the distance of all the Mars rovers combined.

The spacecraft will be small, about 450 kg. Though its scientific instrumentation isn't finalized yet, it's expected to include:

- DraMS (Dragonfly Mass Spectrometer), to identify chemical components, especially those relevant to biological processes.

- DraGNS (Dragonfly Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer), to identify the composition of surface and air samples.

- DraGMet (Dragonfly Geophysics and Meteorology Package), suite of meteorological sensors and a seismometer.

- DragonCam (Dragonfly Camera Suite), a set of microscopic and panoramic cameras to image Titan's terrain and landing sites that are scientifically interesting.

“With the Dragonfly mission, NASA will once again do what no one else can do.” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine.

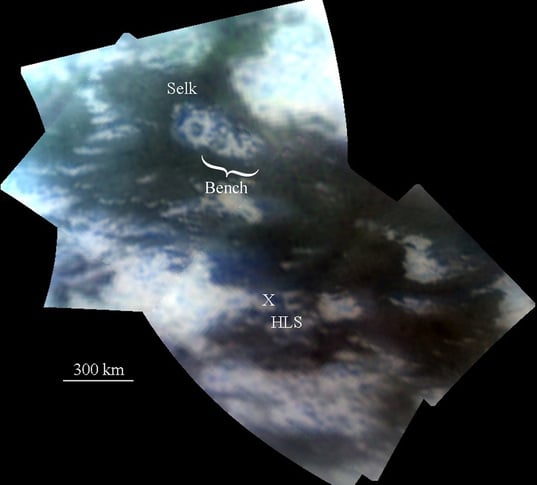

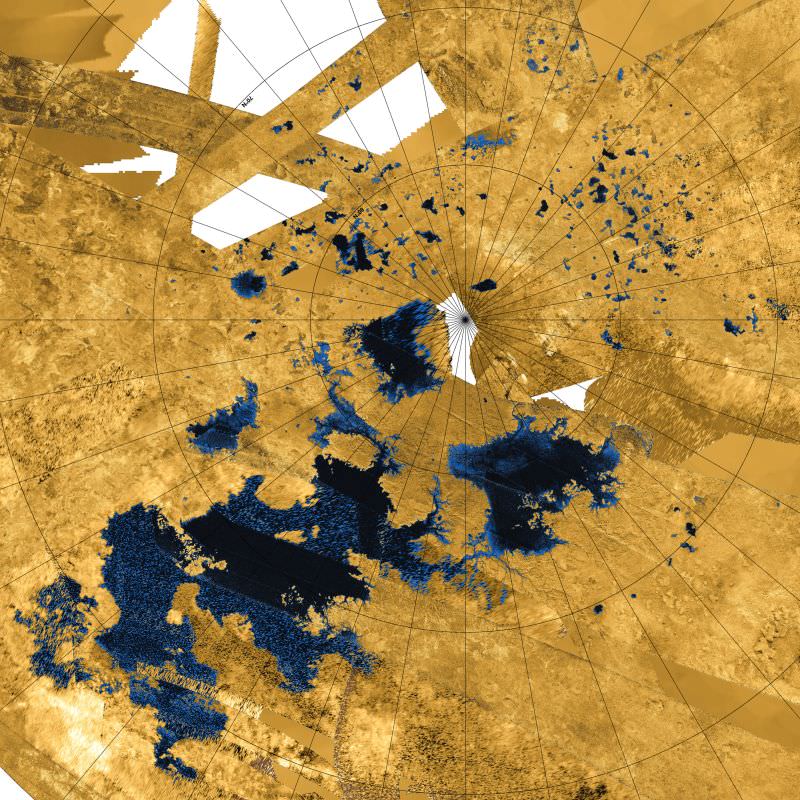

Thanks to the Cassini mission and all the data it delivered, scientists have selected a rich landing site for Dragonfly. It'll land near the equator, at an area called the " Shangri-La Dune Fields." These dune fields are similar to dune fields in Namibia, and the spacecraft will explore them with a series of small short-hop flights. It'll work its way up to longer flights of up to 8 km (5 miles) and will identify promising sites to take samples as it works its way to a feature called the Selk impact crater.

The Selk impact crater is also an intriguing scientific target. It shows evidence of liquid water in its past, and also organic chemicals. Combined with energy, this is the basic recipe for life.

"Titan is unlike any other place in the solar system, and Dragonfly is like no other mission," said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's associate administrator for Science at the agency's Headquarters in Washington. "It's remarkable to think of this rotorcraft flying miles and miles across the organic sand dunes of Saturn's largest moon, exploring the processes that shape this extraordinary environment. Dragonfly will visit a world filled with a wide variety of organic compounds, which are the building blocks of life and could teach us about the origin of life itself."

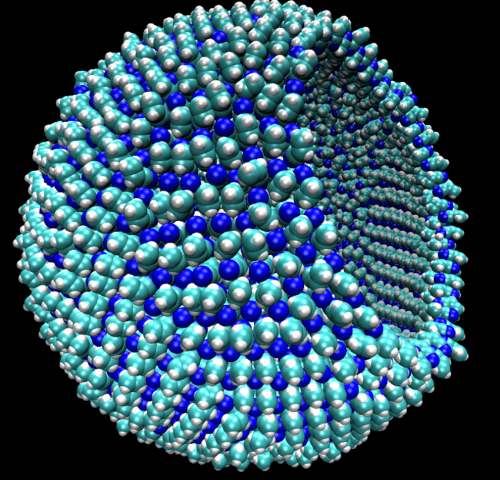

Titan holds scientists' interests because in many ways it is similar to early Earth, and it may hold some clues into how life developed on our planet. Some think that it could even harbor a strange type of life, based not on liquid water, but on liquid hydrocarbons.

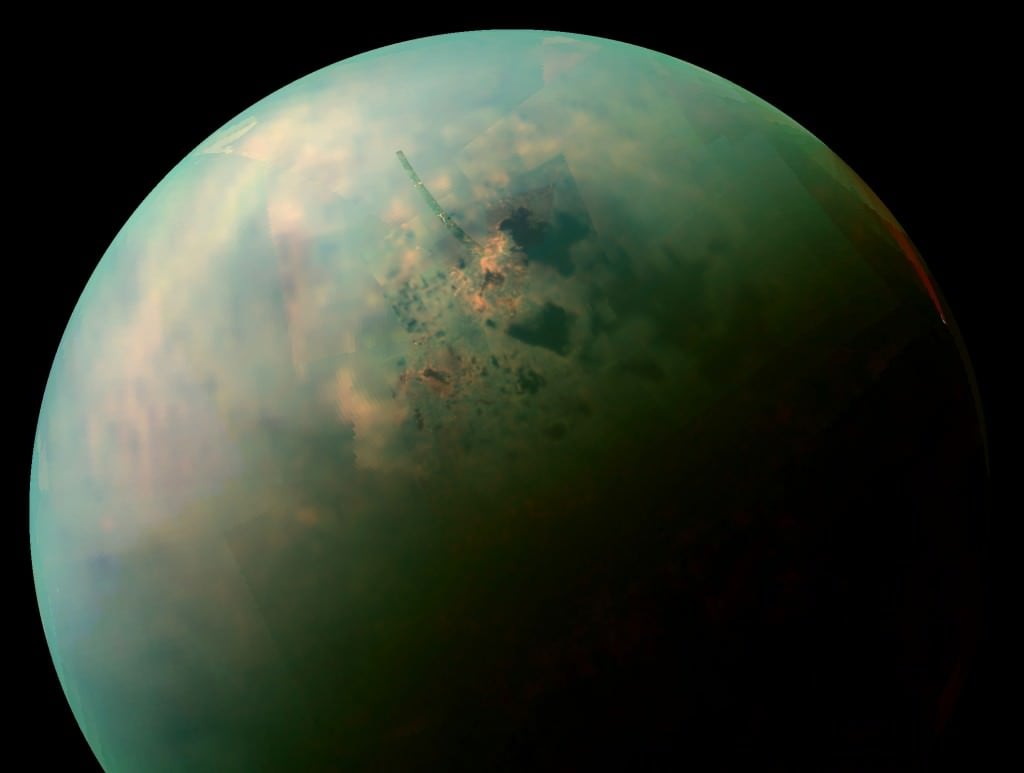

Titan is an exotic place, and is the only moon with much of an atmosphere. The atmosphere is nitrogen-rich, and scientists have discovered complex organic chemicals there, including tholins and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. It's also the only body in the Solar System, other than Earth, with liquids flowing across the surface.

Titan has a nitrogen-based atmosphere like Earth, but unlike Earth, it has clouds and rain of methane instead of water. Other organics are formed in the atmosphere and fall like light snow. The moon's weather and surface processes have combined complex organics, energy, and water similar to those that may have sparked life on our planet.

The temperatures on Titan are frigid, as low as -179.2 C (94 K; ?290.5 °F), so the liquids are hydrocarbons, not water. The surface features are similar to Earths, with lakes and interconnected tributaries in the polar regions. The surface is also geologically young and smooth, with very few impact craters.

"With the Dragonfly mission, NASA will once again do what no one else can do," said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in a press release. "Visiting this mysterious ocean world could revolutionize what we know about life in the universe. This cutting-edge mission would have been unthinkable even just a few years ago, but we're now ready for Dragonfly's amazing flight."

Dragonfly won't reach Titan until the year 2034, so we've got a long time to wait. But the wait will be worth it. Titan is one of the most intriguing scientific targets in the Solar System, right alongside the ocean moons Enceladus and Europa.

This is one of the most anticipated mission announcements of our time, and it'll be fascinating to see what Dragonfly can teach us about this strangely-alien, yet strangely Earth-like world.

More:

- Press Release: NASA's Dragonfly Will Fly Around Titan Looking for Origins, Signs of Life

- Wikipedia: Dragonfl y

- NASA: Titan

Universe Today

Universe Today