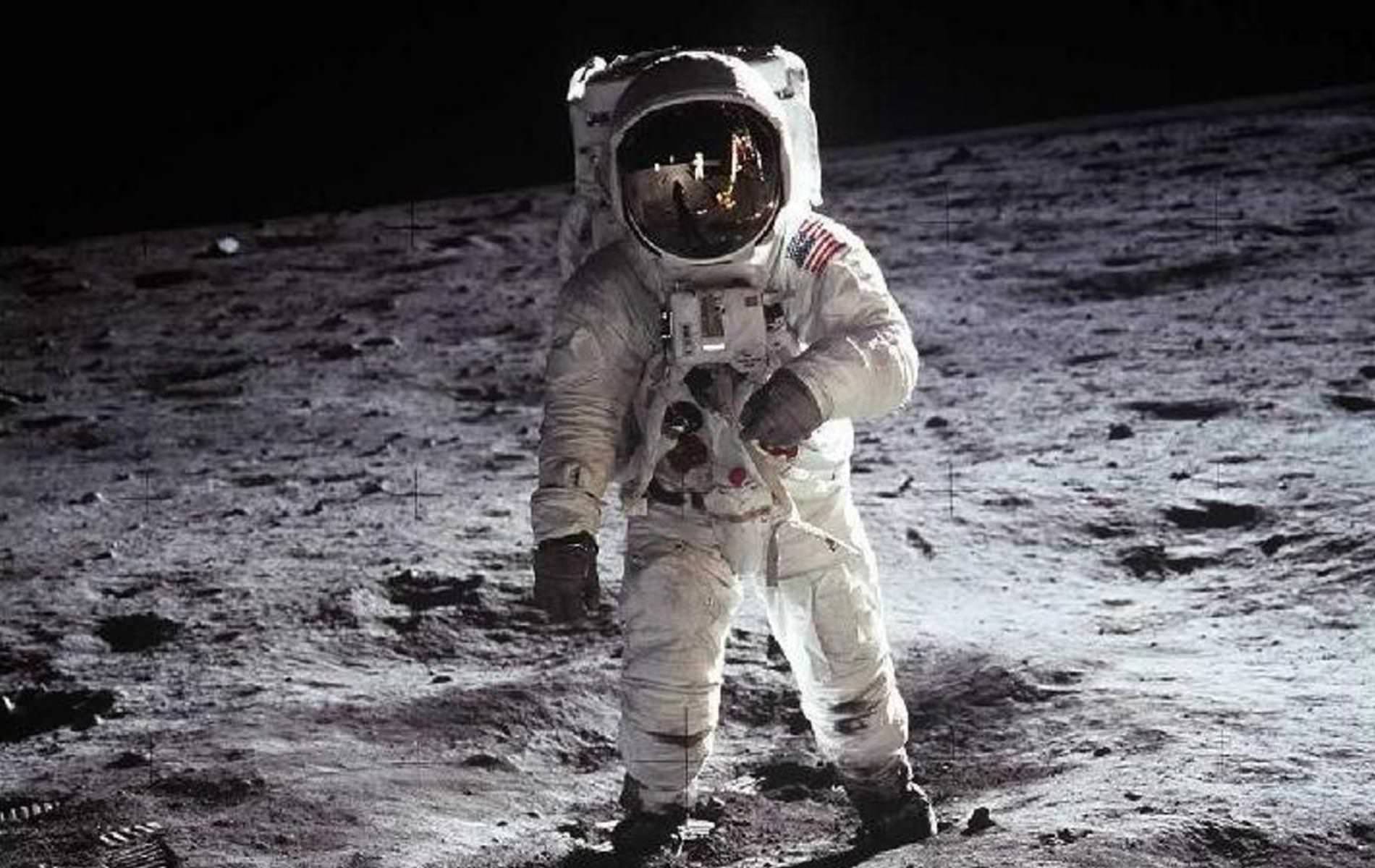

On July 20th, 2019, exactly 50 years will have passed since human beings first set foot on the Moon. To mark this anniversary, NASA will be hosting a number of events and exhibits and people from all around the world will be united in celebration and remembrance. Given that crewed lunar missions are scheduled to take place again soon, this anniversary also serves as a time to reflect on the lessons learned from the last “Moonshot”.

For one, the Moon Landing was the result of years of government-directed research and development that led to what is arguably the greatest achievement in human history. This achievement and the lessons it taught were underscored in a recent essay by two Harva

The essay, titled “Federal Leadership of Future Moonshots“, was recently accepted for publication by Scientific American. The authors included Professor Abraham Loeb and Anjali Tripathi, the Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of Science and Harvard University and a research associate of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and a former White House Fellow in the Office of Science and Technology Policy (respectively).

Loeb and Tripathi begin by addressing how much things have changed since the Space Age, which began with the launch of Sputnik 1 (1957) and peaked with the Apollo missions sending astronauts to the Moon (1969-1973). This age was characterized by national space agencies locked in competition with each other for the sake of committing “firsts”.

Compare and contrast that to today, where what was once the exclusive work of universities and national laboratories

This represents a major departure from the days of the Space Race when space exploration was guided by a grand vision and ambitious goals. This was illustrated by President John F. Kennedy during his “Moon Speech” at Rice University in 1962. This galvanizing speech and the challenge it established culminated in the Moon Landing just seven years later. But as Loeb and Tripathi indicate, it also established a precedent:

“But an enduring part of the Apollo legacy is the outgrowth of other technologies, as byproducts that accompanied solving a grand challenge. These innovations were borne out of the tireless work of men and women across all sectors: government, industry, and academia. The outcome of government-directed research was cross-cutting and more far-reaching than the original, singular goal.”

These benefits are clear when one takes a look at NASA Spinoff, which was founded in 1973 by the NASA Technology Transfer

In addition, a 2002 study conducted by George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute indicated that on average, NASA returns $7 to $21 back to the American public through its Technology Transfer Program. That’s a pretty significant return on investment, especially when you consider the other ways in which it has paid off.

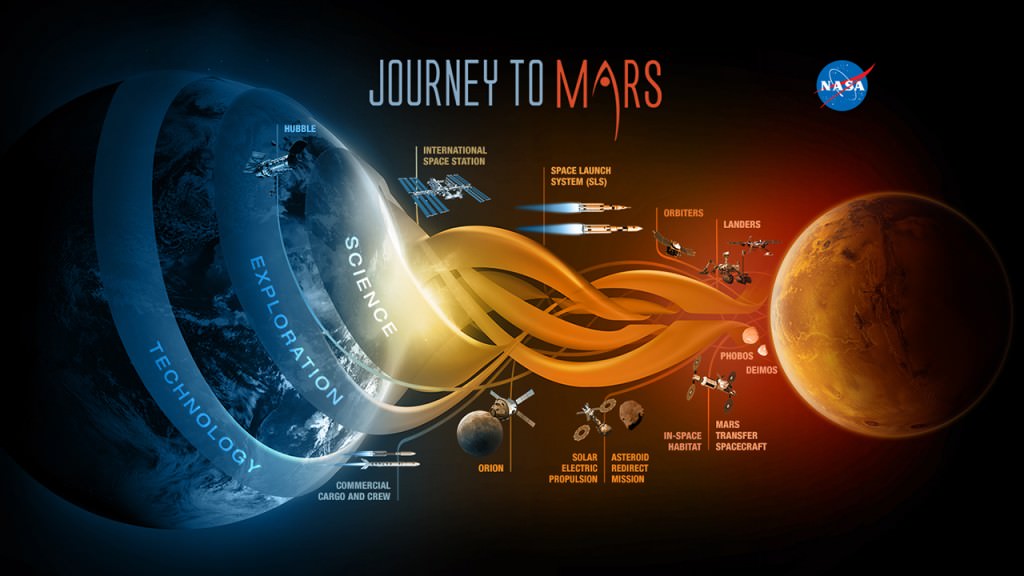

Looking to the future, the desire to set and achieve similar goals has already been expressed – be it returning to the Moon, sending crewed missions onto Mars, and exploring beyond. According to Loeb and Tripathi, the purpose of national organizations such as NASA has not and should not be changed:

“Then, as now, government played a unique role of setting a visionary blueprint for transformative research and providing the necessary funding and coordination… As the future of research is contemplated, similar visionary goals –with broad engagement –must be considered. What should be our next grand vision? And how can we similarly involve all of society in this mission?

To this end, Loeb and Tripathi advocate for the continued use of things like incentive challenges and partnerships between government agencies and the public. These are exemplified by the NASA STMD Centennial Challenges program and the Google Lunar X Prize, which allow for a wider community of thinkers and inventors to be engaged.

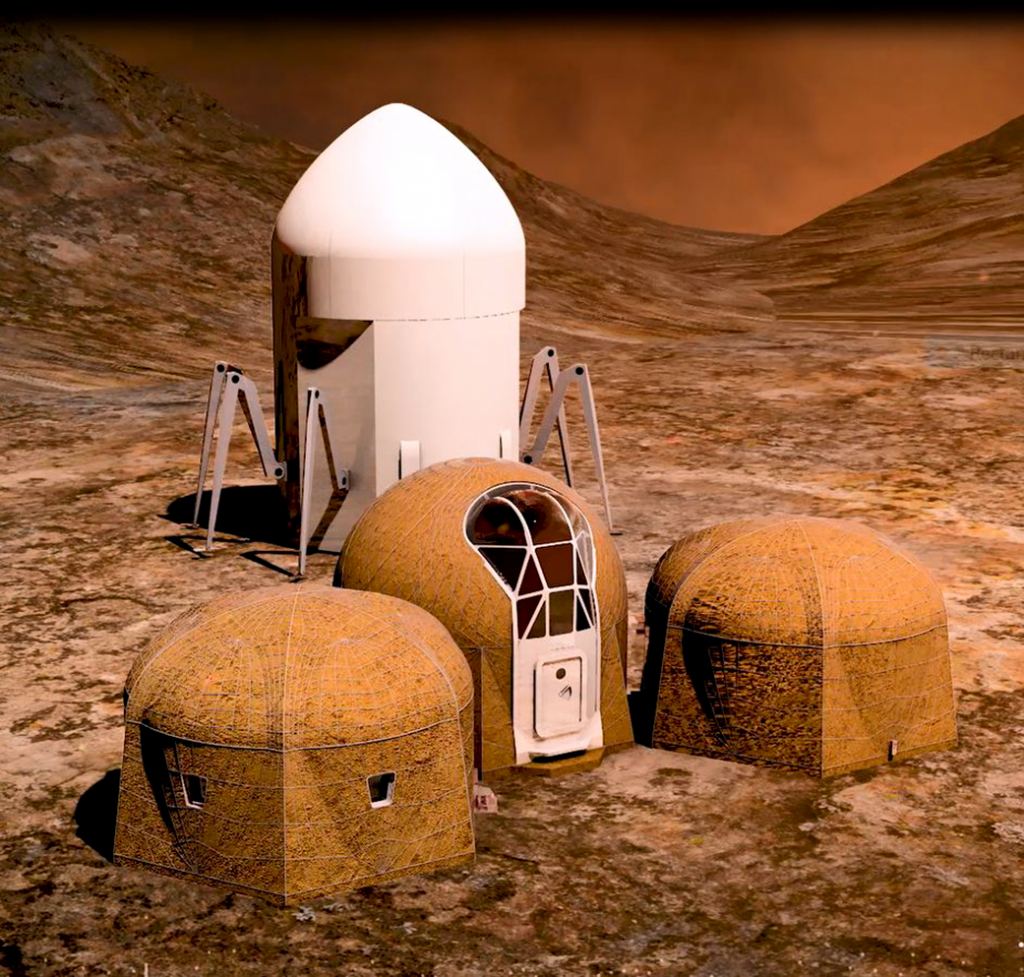

In all cases, teams of students and volunteers are called upon to propose innovative solutions to certain problems, with the winning entries being awarded a monetary prize. Challenges hosted by NASA include the 3-D Printed Habitat Challenge, the Space Robotics Challenge, and the Cube Quest Challenge – which focused on different aspects of near-future space exploration.

“In a time when software and rapid prototyping opportunities are ubiquitous, students, manufacturers

Another strategy they recommend is for federal agencies – like the National Science Foundation (NSF) – to foster “outside the box” thinking. This would likely entail allocating funds to researchers based on larger themes, rather than by discipline. It could also involve setting aside funding for “risky projects that could open up new horizons if successful”, rather than focusing on safe projects that have a high probability of success.

Beyond investing in research, there’s also the need to invest in the infrastructure that enables that research. That means not only universities and national scientific institutions but also mid-scale research infrastructure. Examples include federally-funded nuclear research, originally intended for nuclear weapons, that

Similarly, the Laser-Interferometry Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) – which allowed for the first-ever detection of gravitational waves in – was funded by the NSF. This has led to a revolution in astronomy, some unique proposals (like gravitational wave communications), and the discovery that a large portion of Earth’s gold and heavy elements came from a neutron star merger that took place close to our Solar System billions of years ago.

And of course, there’s also the need for international cooperation, in the form of shared international facilities and programs. The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) is provided as an example since it is a cutting-edge research facility that resulted from international cooperation. Since the US is not a member of CERN and has no comparable facilities, which has left it at a comparative disadvantage.

The European Space Agency (ESA) is another good example. By bringing the federal space agencies of its member states – along with several private aerospace companies – together under one roof, the ESA is able to accomplish things that are financially and logistically beyond the means of its individual member states.

In the future, NASA and the ESA will be collaborating on vital projects such as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), a high-risk, expensive project that is sure to yield immense scientific results. As other opportunities arise for joint-ventures of this kind, Loeb and Tripathi recommend that the US become involved, rather than risk “scientific isolationism”.

In short, it is and always has been about making “Moonshots” happen. Whether it was the creation of NASA sixty-one years ago, the Moon Landing fifty years ago, or the next great leap planned for the future, the need for government-investment remains the same.

Further Reading: Harvard-Smithsonian CfA