To the scientifically uninitiated, it might seem like a frivolous idea: That those slight, wispy clouds that trail behind jet aircraft at such high altitudes could contribute to climate change. But they do.

Scientists love to measure things, and when they measured these contrails, which is short for condensation trails, they found bad news. Though they look kind of beautiful and ephemeral on a summer day, they pack an oversize punch when it comes to their warming effect.

A new study from the German Institute for Atmospheric Physics looked at the cirrus clouds that form when the moisture in the jet engine exhaust freezes into ice crystals. They found that these clouds, which can sometimes persist for hours, account for more climate warming than the carbon in the exhaust. The effect is called Contrail Cirrus Radiative Forcing.

The study is called “Contrail cirrus radiative forcing for future air traffic” and the authors are Lisa Bock and Ulrike Burkhardt. The study was published on June 27 in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, a journal of the European Geosciences Union. It focused in on the expected growth in air travel between 2006 and 2050. They say that contrail cirrus radiative forcing (hereafter called CCRF) is projected to increase by a factor of three by the year 2050.

Jet engine exhaust contains water vapour, along with other substances, including carbon dioxide, sulfur oxide, nitrogen oxide, and unburned fuel. It also contains metal particles and soot particles, and they act as condensation nuclei for the water vapour.

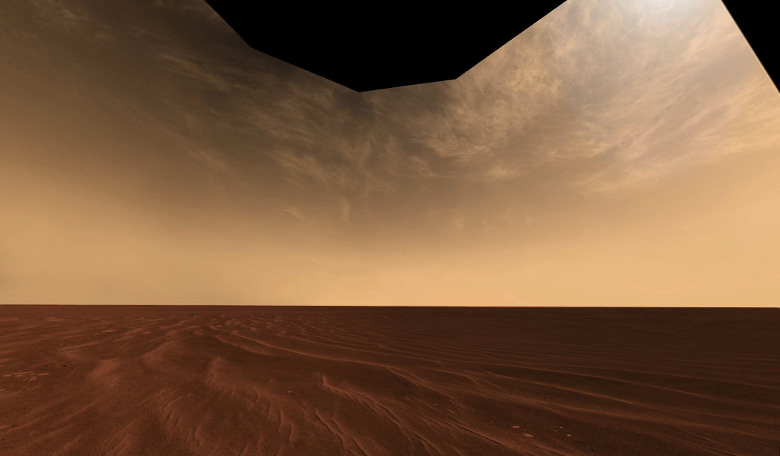

As water vapour comes out in the jet engine exhaust, it rapidly cools in the high altitude. Then it condenses onto soot particles as ice crystals, and forms the condensation trails we’re all familiar with. In scientific jargon, these trails are called contrail cirrus clouds. Though they initially form as telltale streaks, they eventually take more cloud-like shapes.

These clouds can persist for hours, and they can contribute to warming more than the carbon dioxide in the exhaust does. A 2011 study, by one of the same scientists behind this study, showed that these cirrus clouds can have a greater warming effect than the carbon emissions. That’s because of radiative forcing.

Radiative forcing is the different between the sunlight absorbed by the Earth and the amount radiated back into space. In this case, it’s positive radiative forcing, meaning these contrail cirrus clouds are trapping more heat in the atmosphere.

This is a difficult thing to study, because there can be so many variables. The effect of CCRF can vary at different latitudes and in different regions. Projecting into the future is challenging because aircraft will likely be more fuel efficient, cleaner fuels with less soot may be developed, and the state of the climate itself in future decades will alter the effect of CCRF.

But this is still an important study.

“…increasing air traffic is the dominating effect that causes higher global mean contrail cirrus radiative forcing in the future.”

From the paper “Contrail cirrus radiative forcing for future air traffic.

One of the reasons the two scientists are focusing on this issue is that there are opportunities to mitigate the effect of CCRF. According to them, achieving a 50% reduction in exhaust soot could lower the effect of CCRF by 15%.

When Greater Fuel Efficiency Is Bad

Fuel efficiency can make a difference, too, although not in the way we’d expect. According to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), fuel efficiency should improve by 2% per year until 2050. But according to a 2000 study, more fuel efficient jet engines will actually increase the formation of condensation cirrus clouds. That’s because the shape and size of the ice particles themselves effects CCRF, and more efficient fuel changes both those parameters. Yikes.

This is a very detailed study. The authors have taken great pains to produce a useful model, while taking into account all the variables that will shape CCRF’s effect in the future. The type and shape of ice particles, and the altitude, shape, and optical depth of the clouds all change the warming effect of the condensation clouds. It’s a difficult thing to model.

The effect of CCRF is different in different regions of the world, and air traffic itself will not grow to the same degree in each region of the world. It’s a complicated issue. But regardless, CCRF is something that needs to be understood if we’re going to deal with climate change.

This study builds on a large body of previous studies from other scientists around the world. Though the modelling varies from study to study, it all points to the same thing: more air traffic means more warming. As the two scientists say in their paper: “However, all studies agree that increasing air traffic is the dominating effect that causes higher global mean contrail cirrus radiative forcing in the future.”

A 2016 study suggested that climate change itself will mean less CCRF in the future. But if that makes you feel hopeful, park your hopefulness. According to this study, “… changes in contrail cirrus radiative forcing due to the projected increase in air traffic by far outweigh any damping effect that a change in climate may have.”

If you have a bucket list that contains trips to far-flung locales, you may want to reconsider. Travelling is great and makes us feel alive. For young people in the rich parts of the world especially, it’s a rite of passage. But if this study is accurate, and it certainly is detailed and well-researched, then we’re headed for a world where air travel is just not worth it.

And not even more fuel-efficient jet engines can fix it.

Sources:

- Research Paper: Contrail cirrus radiative forcing for future air traffic

- Research Paper: Simulated 2050 aviation radiative forcing from contrails and aerosols

- Research Paper: On the Transition of Contrails into Cirrus Clouds

- Research Paper: Future Development of Contrail Cover, Optical Depth, and Radiative Forcing: Impacts of Increasing Air Traffic and Climate Change

- Scientific American: Why do jets leave a white trail in the sky?

- Research Paper: Global radiative forcing from contrail cirrus