It's all about the detail.

In a way, Mars looks like a dusty, dead, dry, boring planet. But science says otherwise. Science says that Mars used to be wet and warm, with an atmosphere. And science says that it was wet and warm for billions of years, easily long enough for life to appear and develop.

But we still don't know for sure if any life did happen there.

The scientific effort to understand Mars and its ancient habitability has really ramped up in recent years. Now that Spirit and Opportunity are gone, MSL Curiosity is carrying the workload. (NASA's InSight lander is on Mars too, but it's not looking for evidence of life or habitability.)

"There’s definitely great interest in Mars as a dynamic terrestrial world that is not so different than our Earth as some other worlds in our solar system.” Prof. Christopher House, Penn State University

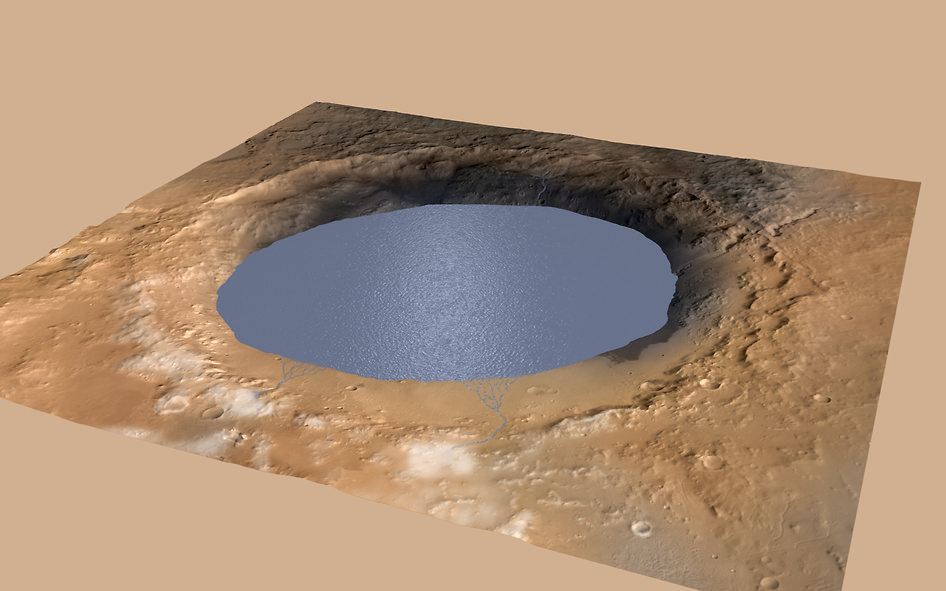

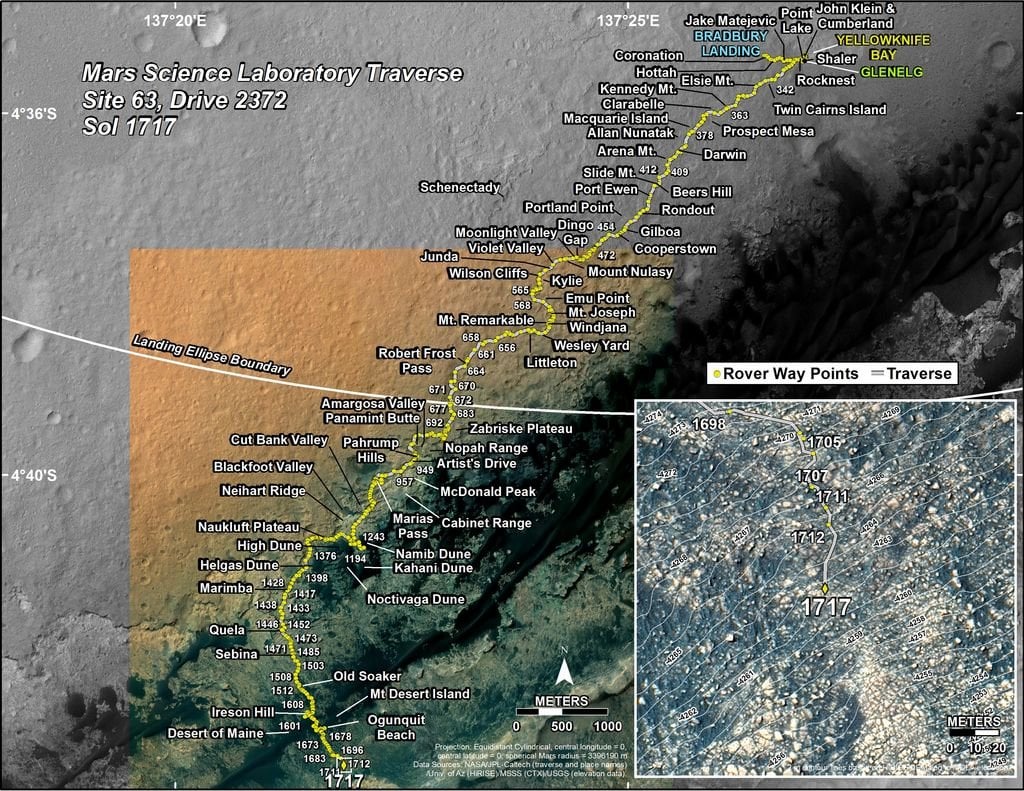

MSL Curiosity is driving around Gale Crater, looking for evidence that life lived there billions of years ago. Gale Crater is a dried up lake bed, and according to scientists, that's the prime location to look for evidence.

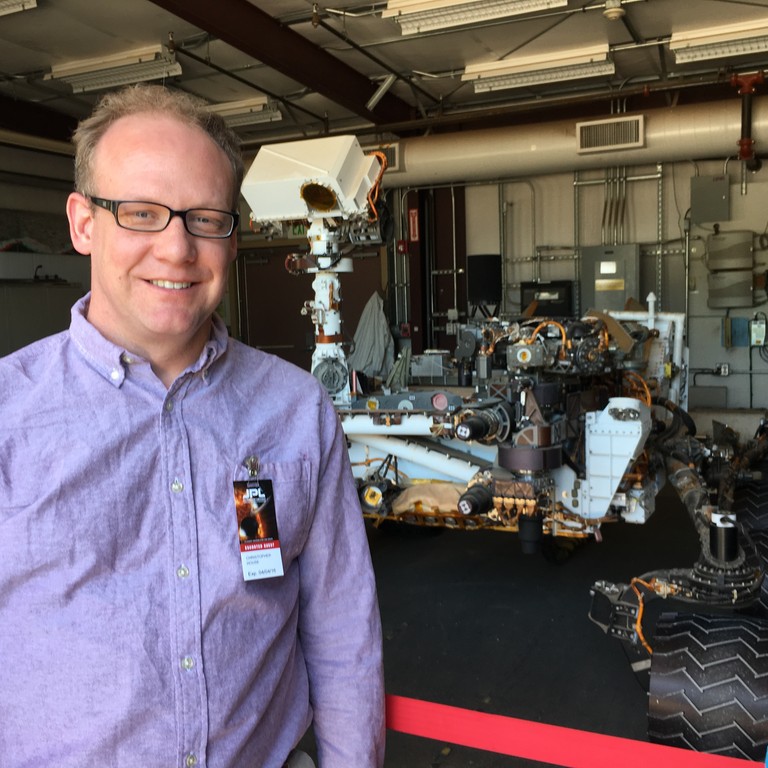

Christopher House is a Professor of Geosciences at Penn State University. He's also a participating scientist with NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission. In a press release from Penn State University, House talked about the MSL mission and what it's like to be involved on a daily basis with the ground-breaking mission.

"Gale Crater appears to have been a lake environment," House said, adding that the mission has found a lot of finely layered mudstone in the crater. "The water would have persisted for a million years or more."

Gale Crater was chosen as the target for Curiosity because it's a complex place. Not only was it a lake bed, meaning there are minerals there that can yield clues to Martian habitability, but that lake was eventually filled with sediment. That sediment turned to stone, which then eroded. That same process is what created Mt. Sharp, the mountain in the middle of Gale Crater, and another of Curiosity's objects of fascination.

"But the whole system, including the groundwater that ran through it, lasted much longer, perhaps even a billion or more years," he said. "There are fractures filled with sulfate, which indicates that water ran through these rocks much later, after the planet was no longer forming lakes."

House works with the Mars Science Laboratory's Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) and sedimentology and stratigraphy teams. The SAM team uses an instrument that heats up rock samples and a mass spectrometer to measure molecules released by the heated samples. The mass of the molecules helps the researchers identify the types of gases released.

House and other scientists are particularly interested in sulfur gases from sulfate and sulfide minerals because the presence of reduced sulfur minerals like pyrite, the most common sulfide mineral, would indicate that the environment could have supported life in the past. This is partly because pyrite needs the presence of organic matter to form in sediment.

Prof. House serves as a lead for the sedimentology and stratigraphy team. As the name implies, that team studies layers of rocks on the surface of Mars to try to understand the environment they formed in. House is also involved in the rover's tactical planning. A few times every month House directs a daily teleconference with scientists around the world to plan Curiosity's operations for the next day on Mars.

“Each time we drive, we wake up to an entirely new field of view with new rocks and new questions to ask.” Professor Christopher House, Penn State University

"It's been fun to be involved in the daily operations, decisions like where to take a measurement, or where to drive, or whether we should prioritize a particular measurement over a different measurement given the limited amount of time on the surface," House said. "Each day is limited by the power that the rover has and how much power the rover will need. It has been a great learning experience for how missions operate and a great opportunity to collaborate with scientists from around the world."

Though it seems to move slowly to us public observers, the pace of Curiosity's day-to-day operations is quick and detailed. According to House, we live in a golden age of planetary science, and it's both exhilarating and bewildering.

"Each time we drive, we wake up to an entirely new field of view with new rocks and new questions to ask," he said. "It's sort of a whole new world each time you move, and so often you're still thinking about the questions that were happening months ago, but you have to deal with the fact that there's a whole new landscape, and you have to do the science of that day as well."

To House, Mars is a fascinating world, and one which we've already learned a great deal about. Mars is still a dynamic place, and we already know that it was likely habitable in the past.

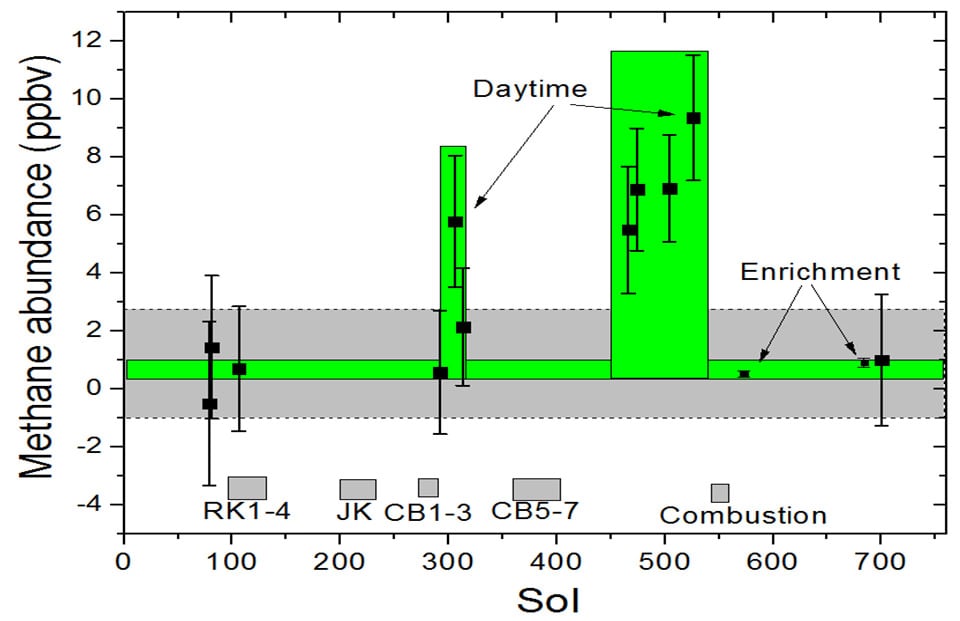

"Missions like this have shown habitable environments on Mars in the past," House said. "Missions have also shown Mars to continue to be an active world with potentially methane releases and geology, including volcanic eruptions, in the not too distant past. There's definitely great interest in Mars as a dynamic terrestrial world that is not so different than our Earth as some other worlds in our solar system."

House is right. While Mars may seem dry, desolate, cold, and lifeless, it's much more Earth-like than other worlds in the Solar System. Venus is a hellhole, Jupiter is a gigantic, radioactive ball of gas, other planets and moons are frigid, dead places far from the light of the Sun, and Mercury is just, well... Mercury.

Curiosity and all the work it does is continually expanding our scientific understanding of Mars. Back in 2014, the rover detected spikes in methane, which is often associated with organic processes. Also in 2014, it found organic carbon compounds. In 2013, the rover also found evidence of an ancient stream-bed on Mars, proving that there was definitely water flowing on the surface in the past.

MSL Curiosity is still going strong since landing on Mars in August 2012. It's initial mission length was targeted at 687 days, but it's still going after more than 2500 days. MSL has already revealed much about Mars, and will keep going until its radioisotope thermoelectric generator runs out of power. Anything else we learn from its mission is gravy.

Universe Today

Universe Today