Why report on an asteroid that has no chance of hitting Earth? Because this asteroid, known as 2006 QV89, has a history. A history of being kind of hard to track.

As the name says, this asteroid was discovered in 2006. It’s a Near-Earth Asteroid (NEA, or NEO, for Near-Earth Object.) An object is classified as an NEO when its perihelion, or closest approach to the Sun, is within 1.3 astronomical units. And if it’s orbit crosses the Earth’s orbit, and the object is larger than 140 meters (460 ft) across, it’s called a Potentially Hazardous Object (PHO.)

2006 QV89 is about 30 meters (100 ft) in diameter, so it’s too small to do enough damage to be a PHO. But we didn’t always know that QV89 wasn’t dangerous.

QV89 was hard to track at first, just like a lot of asteroids. One appears in the sky, scientists have a brief window of time to constrain its size and orbit, then in a few days it can be gone. And it may not be visible again for decades. Based on that brief observational window, astronomers have to decide whether it’s a risk or not, and if it should be put on the risk list. (All that the risk list means is that the objects on it have a non-zero chance of striking list. Not very helpful, really.)

When QV89 was first spotted, it was only visible for 10 days. That’s not much time to figure out if it poses a threat. In this asteroid’s case, nobody was certain. The best estimate was that it had a 1 in 7,000 chance of striking Earth in September 2019. So it was put on the risk list.

Astronomers wanted to track this asteroid, but they didn’t know where to look. If that sounds like an insurmountable problem, it’s not. What scientists do know is where QV89 would have to be in the sky, it it were to strike Earth. That means that even without seeing this thing, we can rule out an impact.

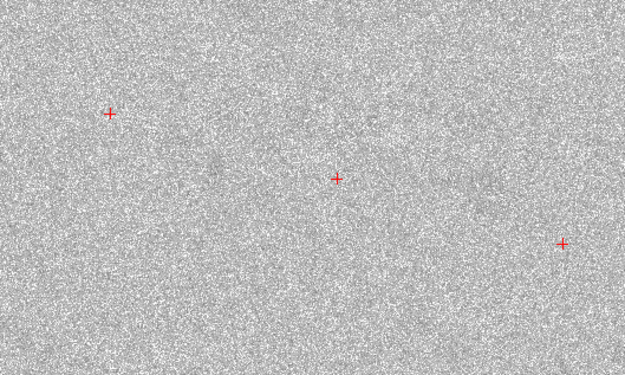

On July 4th and 5th, ESO and ESA astronomers used the Very Large Telescope (VLT) to probe the night sky. Instead of searching in vain for the small rock, they pointed the massive telescope at where the asteroid should be, if it were heading for us. The effort is part of the on-going collaboration between the ESA and the ESO to observe high-risk asteroids. The VLT, with its 8.2 meter primary mirror, has the power to see asteroids moving through space, if you know where to point it.

They saw nothing. They took a very deep image of the area of the sky where 2006 QV89 would have to be if it was going to strike our planet in September, and it wasn’t there.

The above is an image of the region of the sky where asteroid 2006 QV89 would be, only if it was on a collision course with Earth in 2019. The image was taken with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT). The segment shown by the three red crosses in this image shows where the asteroid would be if it was on a collision course. It’s been processed to remove background star contamination, so if it were in this image, asteroid 2006 QV89 would appear as a single bright round light source inside the segment.

Even if the asteroid was smaller than astronomers think, maybe only a few metres across, it would show up. Any smaller than that and the VLT wouldn’t have seen it. But that was the case, then 2006 QV89 would also be harmless. Anything that small would simply would burn up in Earth’s atmosphere.

So we’re safe. For now. There’s officially a zero percent chance of it striking Earth, and the ESA has taken 2006 QV89 off its risk list. We may never hear of it again.