The question of how life on Earth first emerged is one that humans have been asking themselves since time immemorial. While scientists are relatively confident about when it happened, there has been no definitive answer as to why it did. How did amino acids, the chemical building blocks of life, come together roughly four billion years ago to create the first protein molecules?

While that question is still unanswered, scientists are making new discoveries that could help narrow it down. For instance, a team of researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology's Center for Chemical Evolution (CCT) recently conducted a study that showed how some of the earliest predecessors of the protein molecule may have spontaneously linked up to form a chain.

The study recently appeared in the *Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences*. The study was led by Dr. Moran Frenkel-Pinter of Georgia Tech and included multiple researchers from the CCT - which is supported by NASA and the National Science Foundation (NSF) - with assistance from Dr. Luke Leman, and assistant professor of chemistry at Scripps Research, a non-profit medical research institute.

For decades, scientists have had theories about how the first amino acids came together to form protein molecules. Unfortunately, all attempts to verify these theories have so far failed. As Dr. Leman explained:

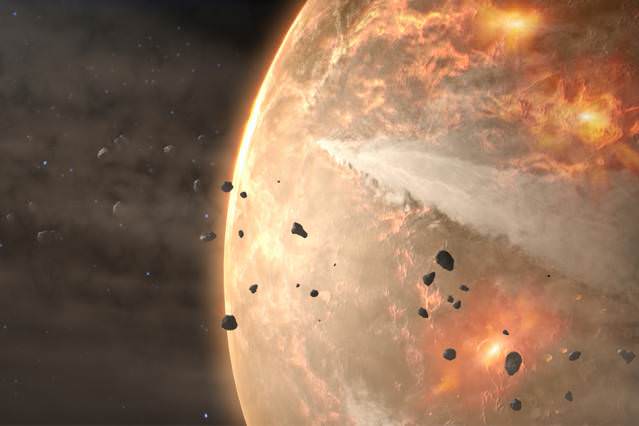

For their study, the research team conducted an experiment where a small selection of amino acids (lysine, arginine, and histidine) were placed together with three non-biological competitor amino acids. The acids were then subjected to conditions similar to what is believed to have existed on Earth during the Hadean Eon (ca. 4 billion years ago).

This consisted of putting the selected amino acids in water containing hydroxy acids, which are known to facilitate amino acid reactions and would have been common on prebiotic Earth. The mixture was then heated to 85 ° C (185 ° F), which sped up the reaction process and caused the water to evaporate. The resulting chemical reactions were then studied.

To their surprise, the biological amino acids spontaneously formed into neat segments that linked together via ?-amine groups. These groups are those that are made of nitrogen and hydrogen and are quite reactive. However, they are also part of the core of amino acids and other amines that form sidechains that extend from the core (which were used in this experiment) are often more reactive. As Dr. Frenkel-Pinter said:

Another surprise was the fact that the biological amino acids beat out the non-biological ones in terms of reactivity. The latter acids, which are not found in proteins today, had the potential to chemically react just as well (or better than) the biological ones. What's more, the team anticipated that the inclusion of these acids would give the biological ones a run for their money and might even lead to the creation of new proteins.

However, the reactions resulted mostly in the formation of peptides (two or more amino acid building blocks linked together) that were closer to today's actual proteins. In particular, the researchers thought that the non-biological amino acids would outcompete the biological amino acid known as lysine and that lysine would not be able to form chains reliably.

In both cases, they were wrong and instead found that the lysine predominantly went into the chains in a way that it is similar to what happens with proteins today. From this, the team hypothesized that prefabricated amino acid chains that are useful in living systems evolved before life had found a way to make proteins.

The fact that their experiment showed that biological amino acids are preferred over non-biological ones may also offer new insight into why just 20 amino acids went into the formation of life. Scientists believe that there were over 500 naturally-occurring acids present on Earth during the Hadean Eon. As Loren Williams, a professor of biochemistry at Georgia Tech, explain e d:

"In the prebiotic Earth, there would have been a much larger set of amino acids. Is there something special about these 20 amino acids, or did these just get frozen at a moment in time by evolution?" In short, the experiment suggests that the kinds of amino acids used in proteins are more likely to link up together because they react together more efficiently and have few inefficient side reactions.

In short, the experiment suggests that the kinds of amino acids used in proteins are more likely to link up together because they react together more efficiently and have few inefficient side reactions. It also lends additional credibility to the theory that most biological polymers formed in wet and dry cycles, which is something that CCT researchers havebeen arguing for years.

This theory, which states that the first proteins occurred on rain-swept dirt flats or sun-baked lakeshore rocks, is at odds with the more conventional narrative that the building blocks of life rely on rare and cataclysmic events, as well as multiple ingredients in order to emerge. By showing that it was likely to be a much more straightforward process, this research could bring us one step closer to unlocking this age-old mystery.

It could also have implications in the search for life beyond Earth. If the building blocks of life are naturally reactive and attracted to one another, then it likely increases the odds that similar chemical reactions took place elsewhere in the Universe!

*Further Reading; Scripps Research*

Universe Today

Universe Today