When astronomers discover a new exoplanet, one of the first considerations is if the planet is in the habitable zone, or outside of it. That label largely depends on whether or not the temperature of the planet allows liquid water. But of course it's not that simple. A new study suggests that frozen, icy worlds with completely frozen oceans could actually have livable land areas that remain habitable.

The new study was published in the AGU's Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. It focuses on how CO2 cycles through a planet and how it affects the planet's temperature. The title is " Habitable Snowballs: Temperate Land Conditions, Liquid Water, and Implications for CO 2 Weathering."

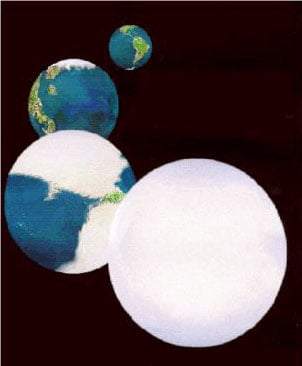

A snowball planet is a planet similar to Earth, but with the oceans frozen all the way to the equator. It's separate from an ice age, when glaciers grow and polar ice sheets expand, sometimes becoming several kilometers thick. In an ice age, the equatorial oceans remain free of ice.

But a snowball planet is more thoroughly frozen than that. On a snowball planet, all of the oceans are covered in ice, including any equatorial oceans. Scientists have considered these planets to be inhabitable, because there's no liquid water on the surface.

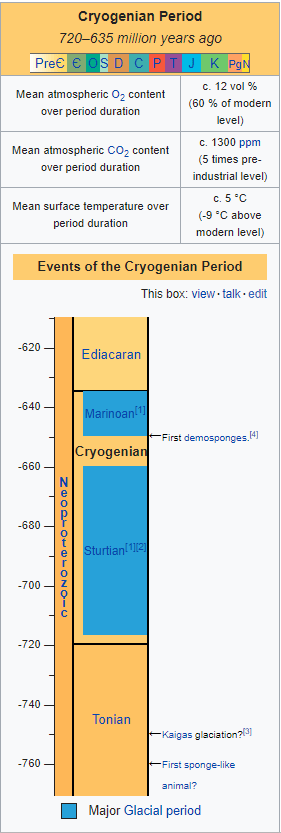

Earth has experienced at least one and maybe as many as three snowball phases in its history. Life endured these phases because the only life forms were marine microorganisms. So the question is, when we look at a snowball exoplanet in its star's habitable zone, is it possible that life is surviving there, after all?

This new research says yes, or at least, maybe.

The lead author of this new study is Adiv Paradise, an astronomer and physicist at the University of Toronto, Canada. Paradise summarizes the situation succinctly: "You have these planets that traditionally you might consider not habitable and this suggests that maybe they can be."

"We know that Earth was habitable through its own snowball episodes, because life emerged before our snowball episodes and life remained long past it," Paradise said in a press release. "But all of our life was in our oceans at that time. There's nothing about the land."

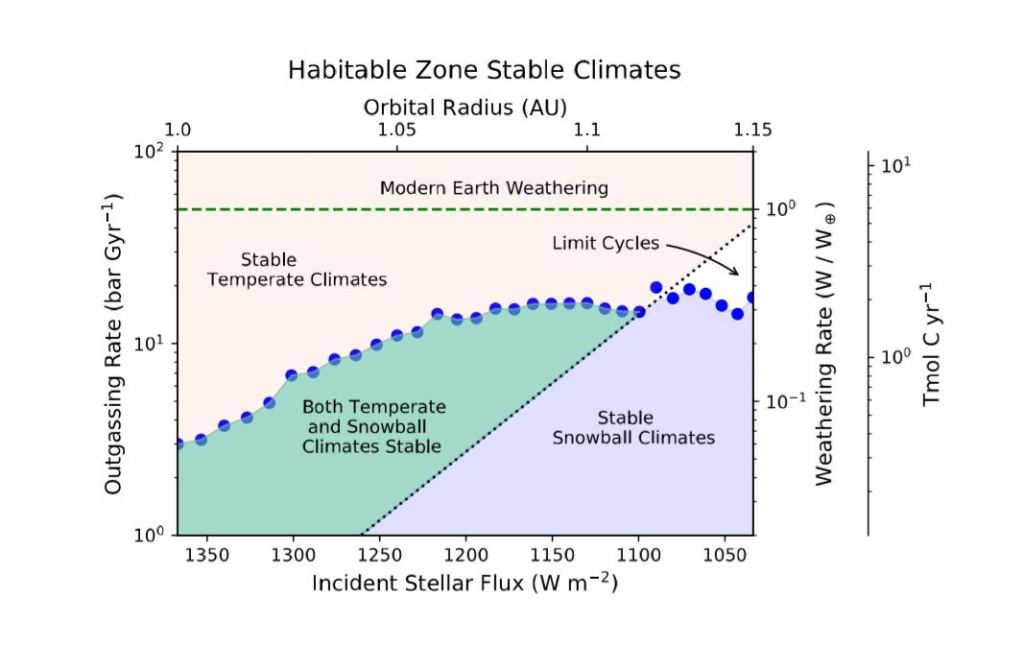

Paradise and the rest of the team wanted to investigate the idea that even on a snowball planet, some land areas might remain life-sustaining. They used computer models to simulate different climate variables on theoretical snowball worlds. They adjusted the configuration of the continents, the amount of sunlight, and other characteristics of their theoretical snowball worlds. They also focused on CO2.

CO2 is a greenhouse gas, of course. It allows a planet's atmosphere to trap heat, and it can help keep a planet temperate. Not enough of it, and a planet can freeze solid. Too much, and temperatures can soar beyond a range that life can survive.

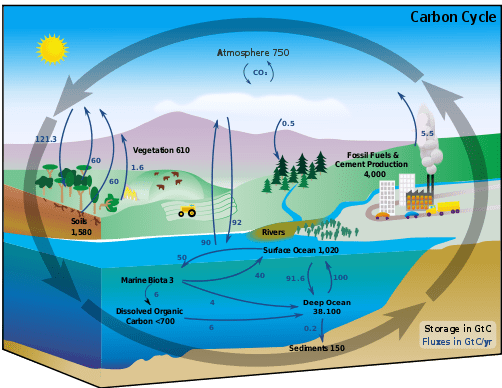

CO2 follows a known cycle in the life of a planet. The amount that persists in the atmosphere is dependent on rainfall and erosion. The water in rainfall absorbs CO2 and turns it into carbonic acid. Once it's on a planet's surface, the carbonic acid reacts with rocks. Those reactions break down the carbonic acid, and it binds with minerals. Eventually that carbon makes its way to the ocean and is stored on the ocean floor.

But once the surface of a snowball planet is frozen solid, none of that can happen. The removal of CO2 from the atmosphere stops dead in its tracks. There's no rainfall, and no exposed land.

But in their simulations, some of the their modeled snowball planets kept losing atmospheric CO2 even after they froze. That implies two things: there must be some ice-free land, and there must be some rainfall.

In some of the simulations, some of the snowball planets were warmer than others. Among those, some of them had land areas that remained warm enough for the carbon cycle to continue: there was both rainfall, and exposed rock. These non-frozen areas were in the center of the continents, far from the frozen oceans. Some temperatures in those areas reached as high as 10 Celsius (50 F.) Since scientists think that life can still continue to reproduce in temperatures as low as -20 C (-4 F.,) then these findings pave the way for life to survive on snowball planets, just as it did during Earth's own snowball phases(s.)

But the study also found something else. Under the right conditions, (or not the right conditions, if you'd like to see more life out there,) a planet can become trapped in a snowball phase and never move out of it. That's all up to the carbon cycle, too.

Scientists used to think that for volcanically-active planets, there would be a gradual release of CO2 sequestered in rocks, and that over time it would warm the atmosphere, since it can't be removed by rainfall. But if there study is correct, then a small amount of exposed land, and the rain falling on it, could balance out released CO2 and keep the planet in a perpetual near-snowball state. Only a small amount of land would ever be ice-free. In that scenario, life might be unlikely.

Overall the results of this study show how complex planets are. Each one is in a unique situation, and the preliminary label of habitable or non-habitable is just a starting point. There are a tremendous number of variables shaping each exoplanet we discover.

It's safe to to say we can rule out a large number of planets in terms of habitability. Hot Jupiters, for example, are scorching hot gas planets, and can never support any kind of life form we can envision.

But for planets in the habitable zone, or on the boundaries, we're not in a position to rule them out, even if they seem unlikely to support life.

More science needed.

Sources:

- Press Release: Study suggests frozen Earthlike planets could support life

- Research Paper: Habitable Snowballs: Temperate Land Conditions, Liquid Water, and Implications for CO 2 Weathering

- Wikipedia: Snowball Earth

- Wikipedia: Cryogenian Period

Universe Today

Universe Today