The past week has been pretty eventful for SpaceX. On Tuesday (Aug. 27th) at 05:00 PM local time (03:00 PST; 06:00 EST), the company conducted its second free-flight test of the Starship Hopper, which saw the test vehicle successfully ascend to 150 m (~500 ft) above the ground and then land in a different spot. This test brings SpaceX one step closer to orbital tests with their full-scale prototypes of the Starship.

But it was what came shortly after this successful test that has people buzzing right now. On Twitter, as Musk was sharing drone footage of the test, he mused about how big SpaceX’s next super-heavy launch system would be. According to Musk, the next-generation system (Starship 2.0, if you will) will be twice as large as the vehicle that is poised to send humans and cargo to the Moon and to Mars.

The statement was made on Wednesday (Aug. 28th) at 04:34 PM PST (07:34 PM EST) and was issued in response to a question by one of Musk’s many followers on Twitter. Specifically, they wanted to know if Musk planned on building a larger version at some point in the future that would more akin to the Starship’s original design.

When asked if future versions measure be 12 m (~40 ft) in diameter, which was specified in the initial design of the Starship – then known as the Interplanetary Transport System (ITS) – or if the engine technology would be upgraded, Musk

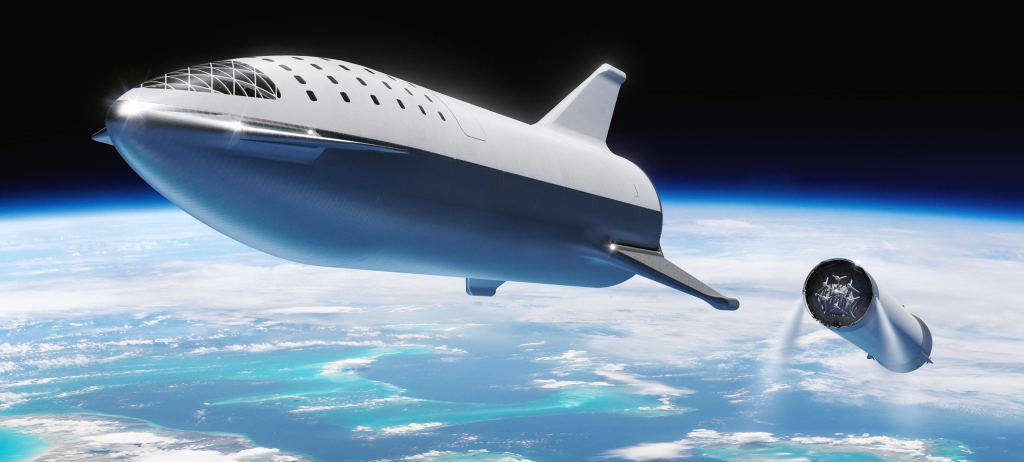

At present, SpaceX is building two full-scale prototypes of the model at their facilities in Boca Chica, Texas, and Cape Canaveral, Florida. These are designated as the Starship Mk. 1 and Mk. 2, which are expected to begin test flights to suborbital altitudes in the near future. When complete, these super-heavy launch vehicles will be the largest and most powerful rockets ever built.

According to the specifications shared by Musk during a presentation at SpaceX headquarters in September of 2018, the Starship element stands 55 m (~180 ft) tall on its own and is capable of generating 11,500 kN (2,600,000

The Super Heavy booster element, meanwhile, will stand at least 70m (230 ft) tall and be capable of generating as much as ~90,000 kN (19,600,000 lbf) of thrust. This will be provided by 30 sea-level-optimized and 7 vacuum-optimized Raptor engines. Based on Musk’s latest hints, that means the Starship 2.0 could be twice as large, standing just under 240 m (~775 ft) tall and 18 m (~60 ft) wide.

As Eric Ralph of Teslarati indicates, accounting for the area and volume that this diameter implies leads to some pretty interesting results. Doubling both the height and width of the rocket, you get eight times the surface area and propellant tank volume. This means that the launch vehicle would weight eight times as much as the Starship 1.0 and would have to generate eight times as much thrust.

Presumably, that would mean that the next-generation of SpaceX super heavies would be able to place payloads up to 800,000 kg (~1.764 million lbs) to Low Earth Orbit (LEO), the Moon, and Mars – provided orbital refueling is an option. That works out to about 800 metric tons (881 US tons). And barring the development of more powerful engines, roughly 60 Raptors would be needed to help this rocket take off!

Granted, this is all speculation at this point. But one cannot deny that it’s an exciting prospect. What’s more, Musk’s allusion to a next-generation spacecraft that doubles the diameter of the current Starship is in keeping with his ambitious nature. As with most things, I guess we’ll just have to wait and see…

Further Reading: Teslarati, Making Life Interplanetary (2017)

Pending further comment from Musk, I’d say the twice-as- high part is Teslarati’s conjecture; but half-again as high would be not unreasonable.

It would seem that Musk is converging on the same solution to economies of scale that von Braun and later Truax found inescapable: really stupid-big boosters and launch systems. Truax also recognized the impracticality of land-launch facilities for such monsters. Musk’s final vision will require a platform at sea: something that size going bang on or near the ground would be more threat than local or state governments would want to license.

But then, he (and Bezos) may as well realize Truax’ in -sea launch proposal. Now, the historically-informed will see where this is going. Yes, except for the pressure-feed concept, these guys are going to opt for some kind of Sea Dragon system, lock, stock, and barrel, and not only built in shipbuilding yards by the sea; but to a large extent designed by shipbuilders.

I fully expect, then, that by next year, you’re going to hear Musk musing about a single engine to power the whole booster. And here is a wrap-up sketch for a 2026 BFR, ready for launch:

*Really big

*Concentric Methalox tank geometry

*Pump-fed single engine

*Low-tolerance fabrication philosophy (trade fine-ISP-tuning for sheer volume of propellant

*In-sea launch

*No full-gasification of LOX and methane

*Once round suborbital booster recovery (lands in the general area it takes off from)

*parachute landing (Yeah, boo-hiss, get it outa your system, but retro-return and landing is out of the question.

Finally: no, ‘instability’ is not some problem specially inherent in really big rocket engines. Every time these things have a scaling-up, they get instabilities, going back even to the Nazi’s design of the V-2 engine. The Saturn’s F-1 instabilities weren’t fully licked until the mid-60’s, not mention a host of other problems.

Rocket-Science: stuff blowing up a lot before it works.

Doubling all dimensions gives: 4 times the area and 8 time the volume. Area is proportional the square of the length, volume to the cube! Article actually says: “Doubling both the height and width of the rocket, you get eight times the surface area and propellant tank volume.”