Springtime on Earth can be a riotous affair, as plants come back to life and creatures large and small get ready to mate. Nothing like that happens on Mars, of course. But even on a cold world like Mars, springtime brings changes, though you have to look a little more closely to see them.

Lucky for us, there are spacecraft orbiting Mars with high-resolution cameras, and we can track the onset of Martian springtime through images.

When winter comes to Mars' polar regions, a thin layer of ice is laid on the surface of the planet. It's not water ice, but carbon dioxide ice. Then when spring comes, as it did in May 2019 at Mars' northern polar region, that CO2 ice sublimates, going directly from solid to vapour without transitioning through a liquid phase.

At Mars' dune fields, this sublimation happens from the bottom up. That's because the winter ice grains that form the layer become nearly transparent, letting the sunlight melt the ice from the bottom. That traps gas between the ice below and the sand above. As warming progresses, the ice cracks, violently releasing the gas trapped under it. As it explodes through the ice, it carries dark sand with it.

The ESA/RosCosmos ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter arrived at Mars in October 2016 and has been studying the planet since then. Part of its instrument payload is the Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS) that, among other things, creates detailed digital elevation models of the surface of Mars.

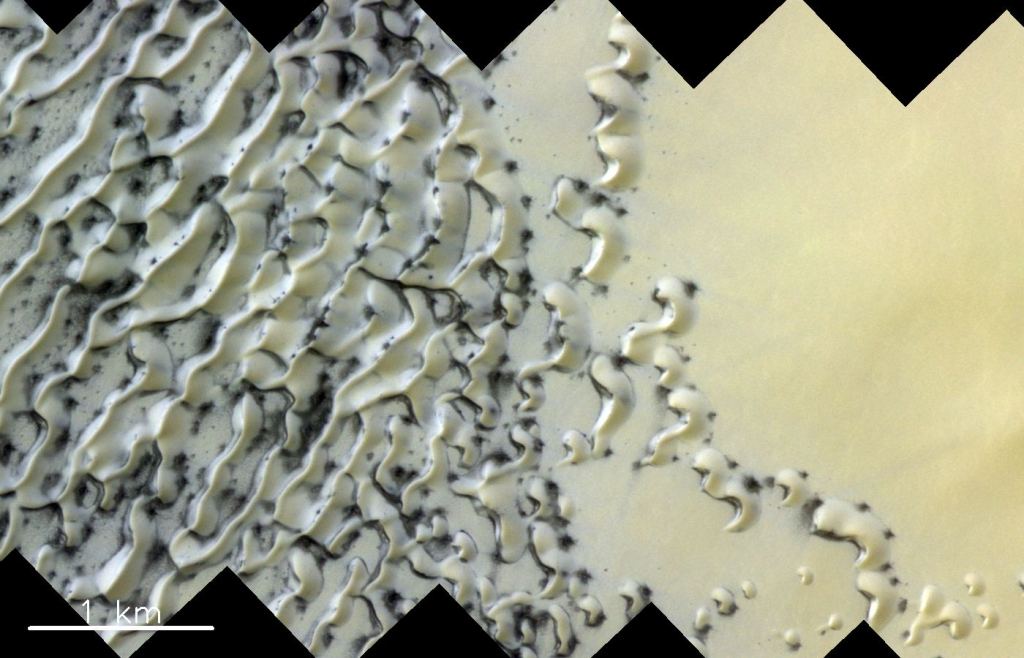

CaSSIS is a high-resolution camera and in May 2019 it captured an image of the melting CO2 at Mars northern polar region.

The image also shows different types of dunes that form on the planet. While the left side of the image looks like dunes as most people might picture them, the right side doesn't. Those are called barchan dunes, or crescent dunes. Those dunes can grow larger and join with each other to from barchanoid ridges. Barchan dunes tell us which way the prevailing wind blows: the curved tips point downwind.

The CaSSIS instrument on the Trace Gas Orbiter also captured images of springtime in the southern polar region, in May 2018. The image shows, again, a dune field, but this time inside a crater. The same type of springtime sublimation is present in that image, with geysers or explosions of buried CO2 ice bursting through the surface ice and carrying sand with it. In this dune field, the sand is carried down the face of the dunes.

Mars' axial tilt is about 25 degrees, a little greater that Earth's 23.4 degrees. The seasons on Mars don't move in lock-step with Earthly seasons. A Martian year is about 687 Earth days, but unlike Earth, Mars' seasons don't each take up a quarter of the year. That's because of its orbit.

While Earth's orbit is nearly circular, and it moves at a stable speed around the Sun, Mars doesn't. It's orbit is more elliptical, and its speed varies. So while Earth's seasons change on the same dates year after year, Mars' seasons don't.

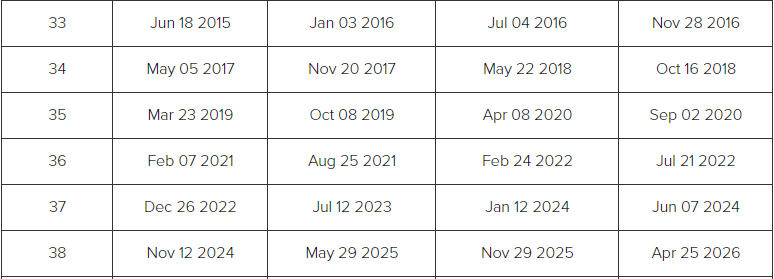

Here's an excerpt of a table from The Planetary Org showing Martian seasons. There are different ways of measuring and marking seasons on Mars, but this method is used by some scientists.

The European Planetary Science Congress will meet this week to discuss, among other things, results and images from the Trace Gas Orbiter.

Universe Today

Universe Today