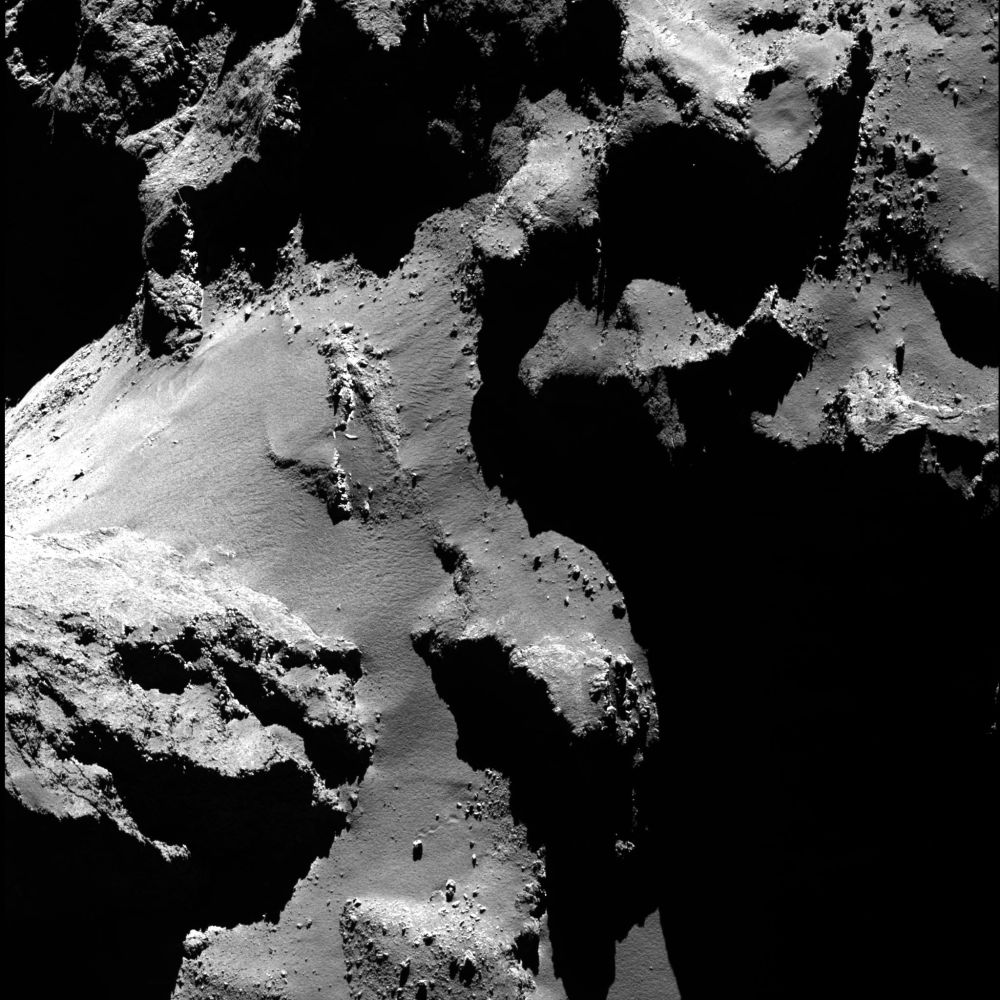

It seems that comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko is not the stoic, unchanging Solar System traveller that it might seem to be. Scientists working through the vast warehouse of images from the Rosetta spacecraft have discovered there's lots going on on 67P. Among the activity are collapsing cliffs and bouncing boulders.

Rosetta spent almost two years at 67P, ending its mission with a hard landing on the comet's surface. During the spacecraft's journey and its two years at the comet, it captured almost 100,000 images. About 3/4 of them are from OSIRIS (Optical, Spectroscopic, and Infrared Remote Imaging System) and the rest are from the NAVCAM. (You can enjoy archives of its images here.)

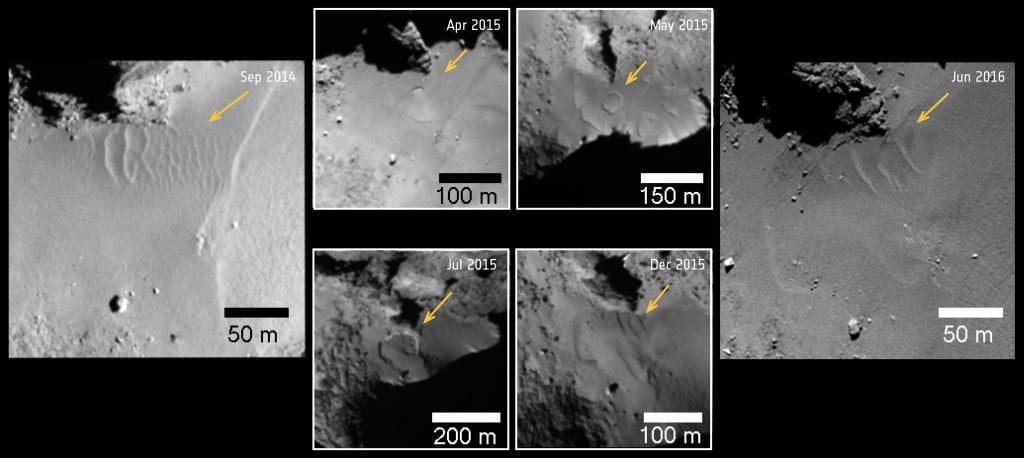

These images are all being analyzed by scientists, and part of that analysis involves images from during and after perihelion. Perihelion is when an object is closest to the Sun, and scientists expect to see the most changes on the comet during that time. By comparing perihelion images with those following perihelion, they hope to gain a better understanding of how the comet evolves.

"Rosetta’s datasets continue to surprise us..." Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta Project Scientist.

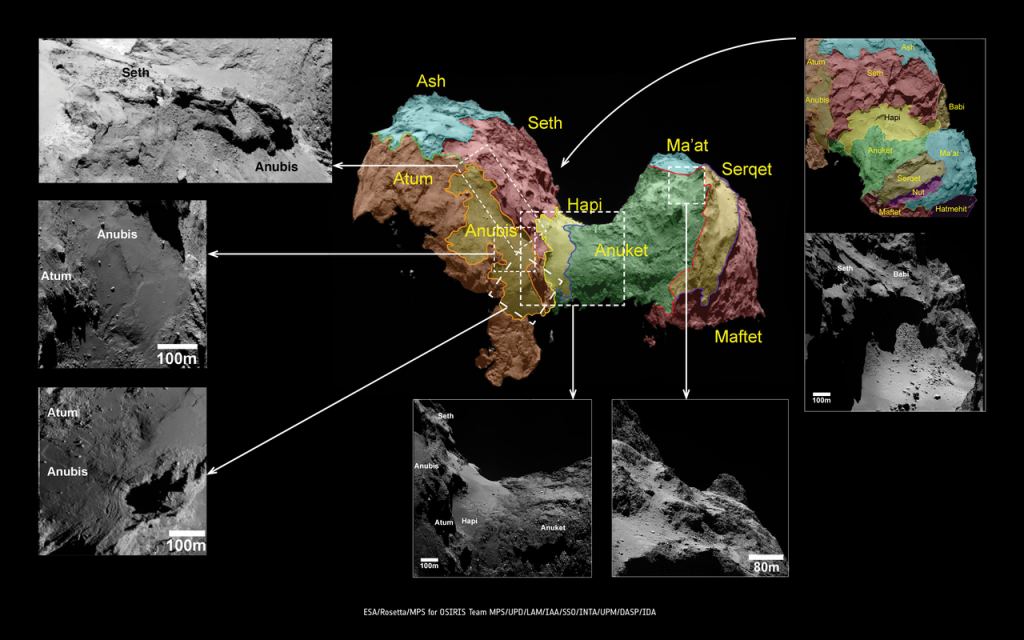

There's a lot going on 67P's surface. A fracture in the comet's neck region grew, patterns of circular shapes in smooth terrain changed over time, sometimes growing up to a few meters per day. There were also boulders moving across the surface. Some of them were tens of meters across and moved hundreds of meters. Other boulders left the surface completely and were ejected into space.

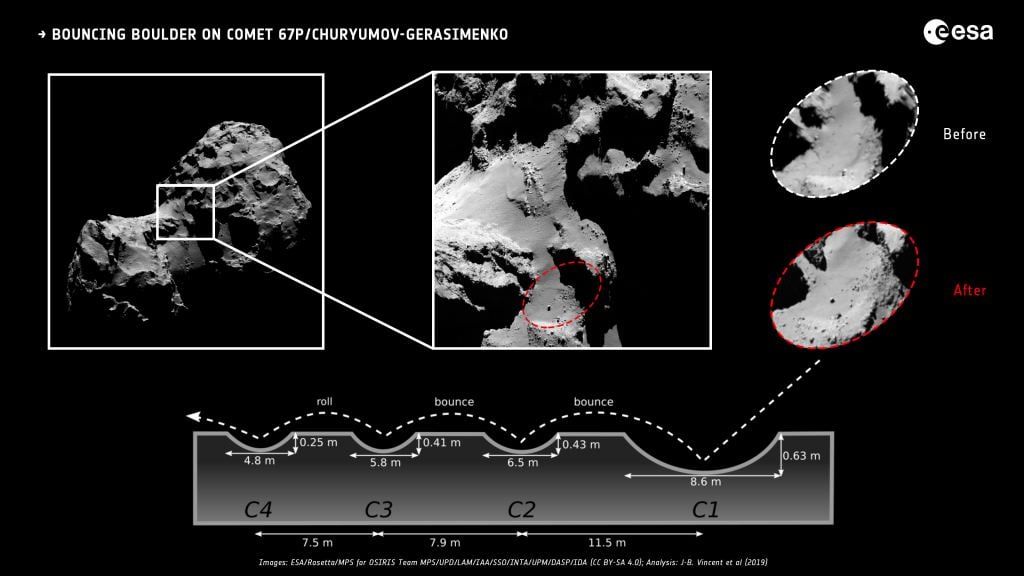

Comet 67P is made of two lobes with a smooth neck connecting them. Over the course of Rosetta's mission the neck region underwent a lot of changes. Images show a 10 meter boulder that fell from a cliff and rolled and bounced along the smooth surface, leaving a trail of bounce marks in the soft material.

"We think it fell from the nearby 50 m-high cliff, and is the largest fragment in this landslide, with a mass of about 230 tonnes," said Jean-Baptiste Vincent of the DLR Institute for Planetary Research, who presented the results at the EPSC-DPS conference in Geneva today.

"So much happened on this comet between May and December 2015 when it was most active, but unfortunately because of this activity we had to keep Rosetta at a safe distance. As such we don't have a close enough view to see illuminated surfaces with enough resolution to exactly pinpoint the 'before' location of the boulder," Vincent said in a press release.

Calling it a boulder may be a little misleading. Comet 67P's material is much weaker compared with ice and rock on Earth. Boulders on the comet are about 100 times weaker than packed snow is here on Earth. But studying them on different locations on the comet's surface gives clues to the properties of the boulders themselves, and of the material they land on.

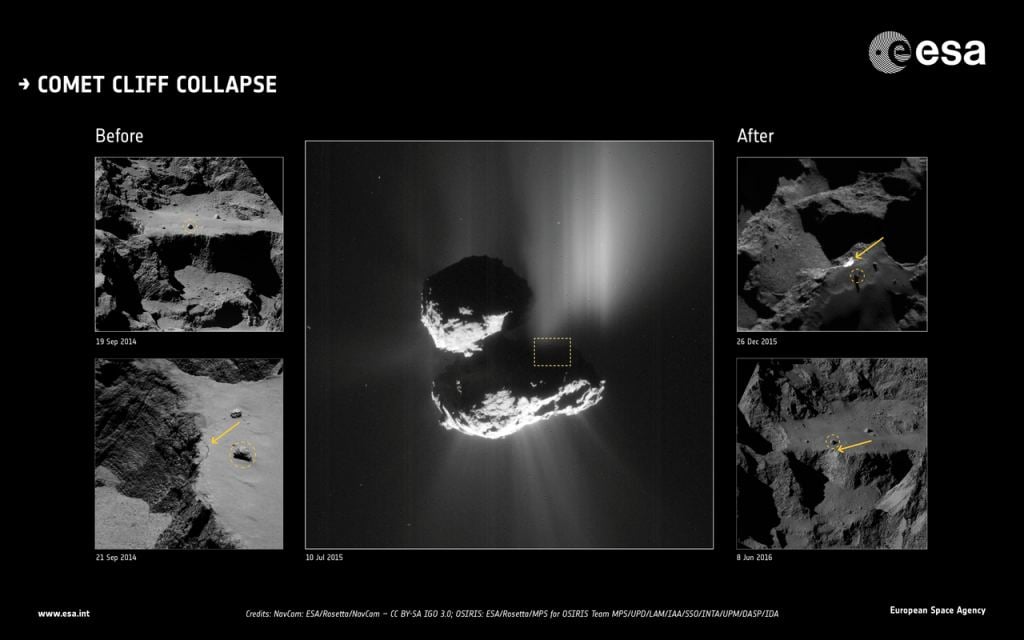

OSIRIS images also show cliffs collapsing at different locations on the comet. One of those collapses involved a 70 meter wide segment of the Aswan cliff falling in July 2015.

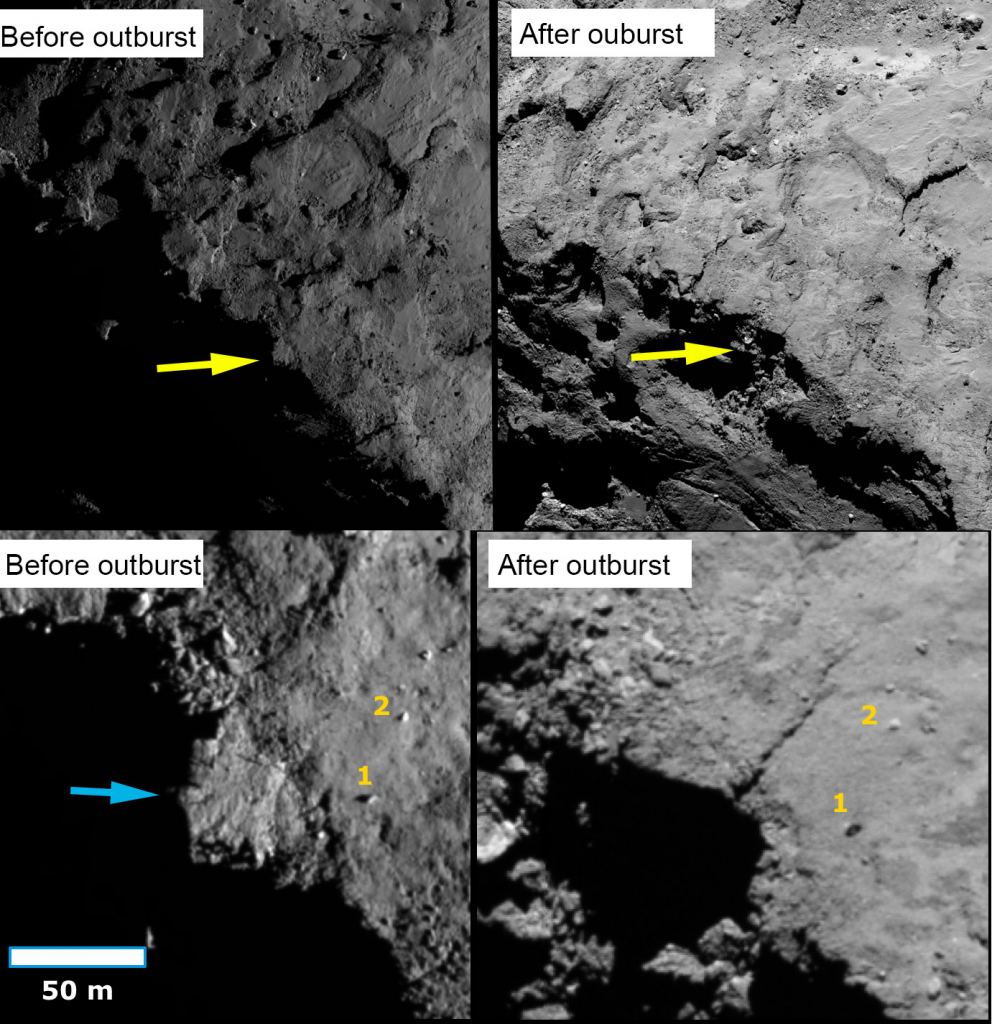

But scientists think they've spotted an even larger cliff collapse. That one is linked to another bright outburst from the comet seen in images from September 12, 2015. "This seems to be one of the largest cliff collapses we've seen on the comet during Rosetta's lifetime, with an area of about 2000 square metres collapsing," said Ramy El-Maarry of Birkbeck, University of London, also speaking at EPSC-DPS today.

https://gfycat.com/elaborateagonizingiridescentshark This bright outburst came from the 2,000 sq. m. cliff collapse. Image Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA (CC BY-SA 4.0)

"Inspection of before and after images allow us to ascertain that the scarp was intact up until at least May 2015, for when we still have high enough resolution images in that region to see it," says Graham, an undergraduate student working with Ramy to investigate Rosetta's vast image archive. "The location in this particularly active region increases the likelihood that the collapsing event is linked to the outburst that occurred in September 2015."

Perihelion puts a lot of stress on a comet. The huge increase in solar energy reaching the surface drives a lot of changes. This was especially true in 67P's southern hemisphere, which received most of the energy.

When scientist examine debris on the comet closely, they find that the surrounding regions near the collapse probably suffered other large erosion events in the past. The blocks of debris are in variable sizes, some up to tens of meters in size. But the boulders from the observed Aswan cliff collapse are only a few meters in diameter.

"This variability in the size distribution of the fallen debris suggests either differences in the strength of the comet's layered materials, and/or varying mechanisms of cliff collapse," adds Ramy.

Scientists studying 67P say that observing large events like cliff collapses opens a window into the internal structure of the comet. That knowledge helps piece together the overall history of the comet's formation.

"Rosetta's datasets continue to surprise us, and it's wonderful the next generation of students are already making exciting discoveries," adds Matt Taylor, ESA's Rosetta project scientist.

Universe Today

Universe Today