It’s time to update the rules. That’s the conclusion of a panel that examined NASA’s rules for planetary protection. It was smart, at the dawn of the space age, to think about how we might inadvertently pollute other worlds with Earthly microbes as we explore the Solar System. But now that we know a lot more than we did back then, the rules don’t fit.

The Planetary Protection Office (PPO) handles these rules and how they apply to spacecraft. Not just for NASA, but for other partner nations too. The Planetary Protection Independent Review Board (PPIRB) produced this new report. The PPIRB was chaired by Alan Stern, a well-known American planetary scientist, and the principal investigator for NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto.

Whenever humans send a spacecraft to another body, there’s a risk of contaminating that body with microbes from Earth. Eliminating or lowering that risk is the only way to guarantee integrity in the search for life. Great pains are taken to sterilize spacecraft, but the risk is never zero. Spacecraft are prepared in sterile clean rooms before launch, and back in the 1970s, the Viking landers were sterilized in huge ovens built just for that purpose.

Conversely, we need to protect Earth from any unwanted visitors that might come back to visit us on one of our spacecraft. It might sound like the stuff of science fiction, but since we don’t yet know what microbes might exist on Mars, Enceladus, or some other world, we have to protect against contaminating Earth.

The Office of Planetary Protection assists in the construction of sterile spacecraft, or what they call “low biological burden” spacecraft. They also help develop low-risk flight plans that help protect other bodies, and Earth as well. The OPP also helps develop workable space policy to meet their aims.

But is it really necessary?

According to this new report, with more and more space exploration, and with more and more countries and commercial players involved, the old set of rules may need to be updated.

“The landscape for planetary protection is moving very fast. It’s exciting now that for the first time, many different players are able to contemplate missions of both commercial and scientific interest to bodies in our solar system,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “We want to be prepared in this new environment with thoughtful and practical policies that enable scientific discoveries and preserve the integrity of our planet and the places we’re visiting.”

Many of the standards were put in place during the ’60s and ’70s. Our knowledge of the Moon and Mars, the most frequently visited bodies, has grown since then. The entire lunar surface was initially classified as important to the study of the origins of life. But that hasn’t held up, and now not many scientists think of the Moon as very significant in that study. At least not all of it.

It’s possible that the lunar poles played a role in the history of life, because they have long-lived deposits of water. But according to the PPIRB, there’s no reason to think that the rest of the Moon does. According to them, different regions on the Moon should have different standards for protection.

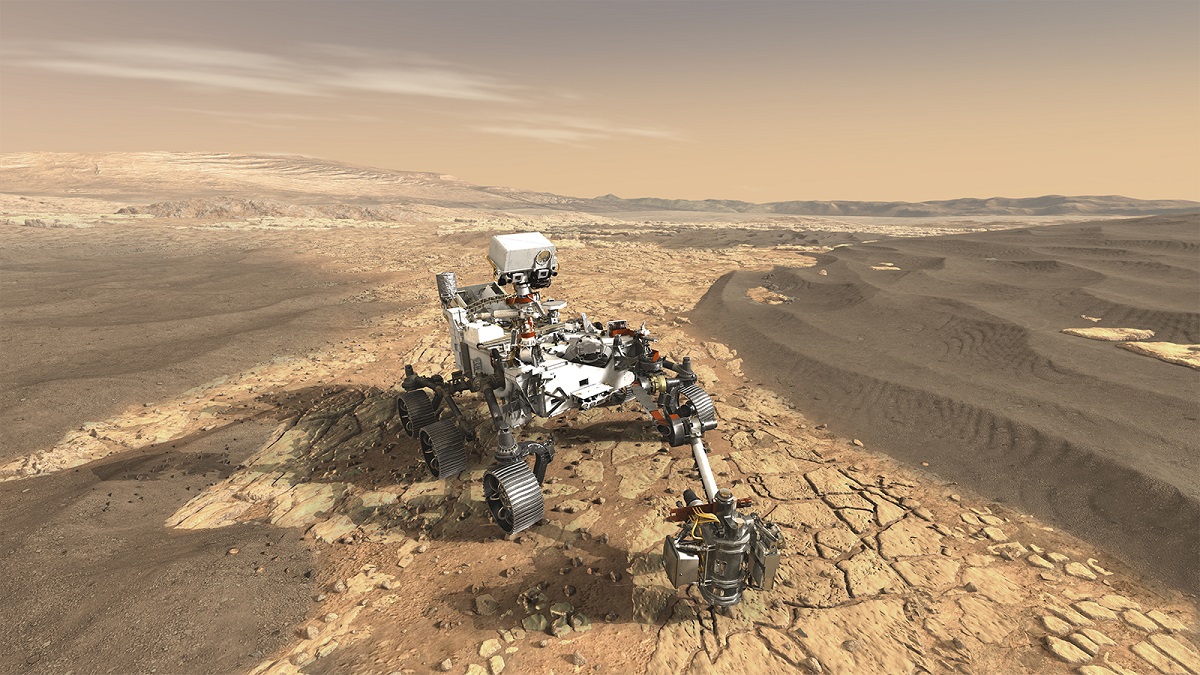

The Moon, and the Lunar Gateway, are likely staging points for future missions to Mars. Is there some risk of cross-contamination between the two? What about when spacecraft return samples to Earth, as the Mars 2020 rover will?

The reality is that material from Mars has been carried to Earth in orders of magnitude greater than any sampling humans can ever do. There’s been a natural flow of Martian material to Earth over billions of years, as meteors strike Mars and send debris into space. Some of that debris has landed on Earth. The PPIRB said the overall risk of contaminating Earth with Martian material should be reviewed.

“In particular, the risk of adverse effects Martian material poses to the terrestrial biosphere should be re-evaluated in light of the ongoing, established, natural transport of Martian material to Earth.”

PPIRB Report, 2019.

The PPIRB isn’t suggesting that all precautions should be removed. One of their recommendations is that a special facility be constructed to receive Martian samples. In their report, they call it the Mars Sample Return Facility (MSRF.) This is not only for scientific reasons, but also to assure people that appropriate precautions are being taken.

“Significant effort is being put into the MSR architectures to ensure there will be no harmful interference with Earth’s biosphere.”

PPIRB Report, 2019.

From the PPIRB report: “As the first restricted Earth return since Apollo, MSR will be a uniquely high profile mission. Significant effort is being put into the MSR architectures to ensure there will be no harmful interference with Earth’s biosphere. This includes NASA work (alongside international partners) to “break the chain of contact” with the Mars environment during sample collection procedures on Mars 2020, the Sample Retrieval Lander and return procedures with the Earth Return Orbiter.”

Part of the effort to update Planetary Protection rules is driven by practical reality. There will be more and more commercial activity in space, and those endeavours need effective and streamlined rules to operate with.

“Planetary science and planetary protection techniques have both changed rapidly in recent years, and both will likely continue to evolve rapidly,” Stern said in a press release. “Planetary protection guidelines and practices need to be updated to reflect our new knowledge and new technologies, and the emergence of new entities planning missions across the solar system. There is global interest in this topic, and we also need to address how new players, for example in the commercial sector, can be integrated into planetary protection.”

Recent events on Mars support the review of Planetary Protection rules. Right now, the MSL Curiosity rover is seven years into its mission. Its over-arching goal is to assess whether Mars ever had an environment that could’ve supported microbial life. It’s doing that by exploring Gale Crater, and slowly working its way up Mt. Sharp, or Aeolis Mons.

Curiosity passed by some rocks with dark streaks on them, and Curiosity scientists pointed out that the streaks are likely water, maybe seasonal seeps. Some of the Curiosity team wanted to investigate these streaks. But the Planetary Protection office was concerned about the possibility of contaminating those seeps. Even though Curiosity was sterilized on Earth, with some parts being baked at 110 C for almost a week, the moving of a drill bit to the rover’s robotic arm after sterilization violated the Office of Planetary Protection’s protocols. Staff at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory responsible for MSL Curiosity were unhappy.

The ocean moons in our Solar System are also future targets in the search for life, especially Europa and Enceladus. What kinds of protection should they receive when our spacecraft visit them? The PPIRB report addressed that issue.

“The fraction of terrestrial microorganisms in spacecraft bio-burdens that has the potential to survive and amplify in ocean worlds is likely to be extremely small.”

PPIRB Report, 2019.

As the report says, “The fraction of terrestrial microorganisms in spacecraft bio-burdens that has the potential to survive and amplify in ocean worlds is likely to be extremely small.” The report goes on to say that there’s almost no possibility that any indigenous life on Enceladus, Europa, or even Titan, has the same origins as Earth life, and that there’s no way scientists wouldn’t tell them apart.

“Any such life would be readily distinguishable from terrestrial microorganisms using modern biochemical techniques. As a consequence of these findings, the current bioburden requirements for Europa and Enceladus missions (i.e., <1 viable microorganism) appear to be unnecessarily conservative.”

NASA has received the report from the PPIRB and intends to develop new protocols. It’s likely that the surface of Mars, and the Moon, will be divided into zones. Some will be considered more important in the search for life and stricter guidelines will be in place. Others will be less restrictive.

But there’s another angle in all of this. Since each mission to Mars has an inherent risk of contaminating that planet with Earthly microbes, shouldn’t we make sure we investigate potentially life-bearing zones sooner rather than later? If so, we’ll need updated protocols sooner than we might think.