Do you wonder how astronomers find all those exoplanets orbiting stars in distant solar systems?

Mostly they use the transit method. When a planet travels in between its star and an observer, the light from the star dims. That’s called a transit. If astronomers watch a planet transit its star a few times, they can confirm its orbital period. They can also start to understand other things about the planet, like its mass and density.

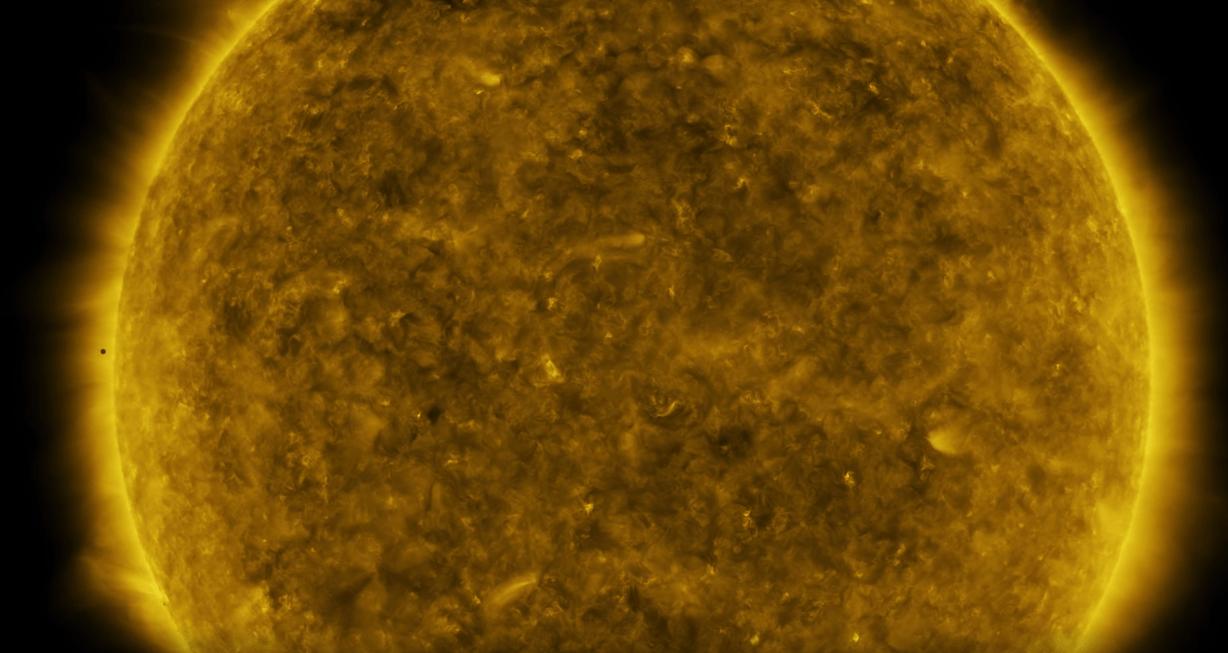

The planet Mercury just transited the Sun, giving us all an up close look at transits.

Two spacecraft had excellent seats for the event: NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO,) and the ESA’s Proba-2.

Mercury transits the Sun only 13 or 14 times per century. The last one was in May 2016, and the next one will be in 2032.

When astronomers detect an exoplanet with the transit method, it’s only the first step to understanding the planet.

Understanding the planet begins with understanding the star it orbits. Astronomers can measure the star’s size by observing its spectrum. Once they know the star’s size, then the details of the dip in light caused by the planet’s transit can tell them the size of the planet.

Then astronomers can use another tool, the radial velocity method, to determine the planet’s density. Even a massive host star will feel the gravitational tug from a tiny orbiting planet. As the exoplanet tugs on its host star, the star moves ever so slightly. That makes the star’s light shift, which astronomers can measure. By combining that measurement with the planet’s size, astronomers can find the density of the exoplanet.

Of course, we already know a ton about Mercury. Here are some of the basic facts:

- Mercury needs only 88 days (actually just under 88 days) to orbit the Sun. It’s the quickest planet to do so, hence its name.

- Mercury is tidally locked to the Sun in what’s called a 3:2 resonance.

- It has the smallest axial tilt of any planet at only 1/30th of a degree.

- Mercury has probably been geologically active for billions of years.

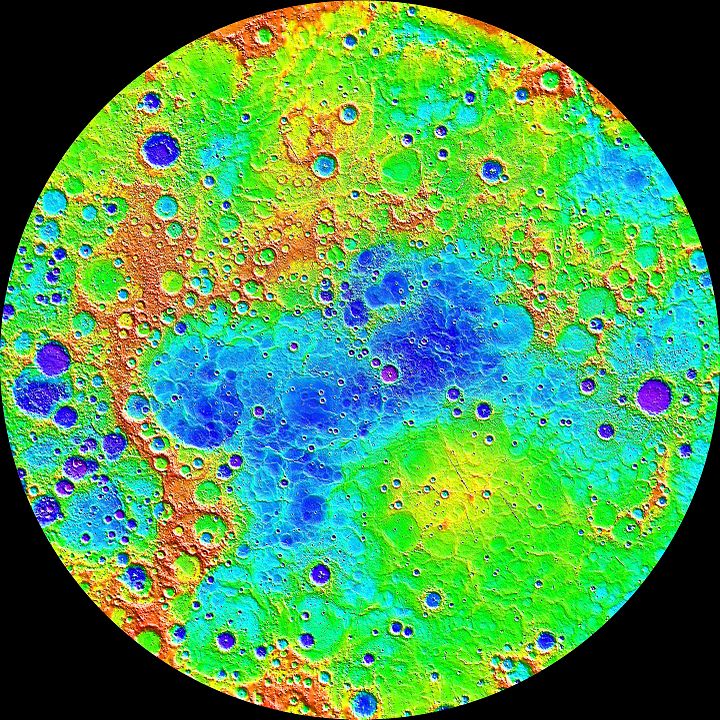

- One of the largest impact craters in the Solar System, the Caloris Basin, is on Mercury.

Even with all we know about Mercury, there are still many questions. But it takes orbiters and landers to answer those questions. If you’re wondering why we haven’t any orbiters around Mercury, and no rovers or landers, there are good reasons.

Mercury’s position so close to the Sun means that any spacecraft that visits Mercury has to contend with the Sun’s powerful gravity. It’s much more complicated than sending an orbiter to Mars, for example. Mercury’s velocity is very high, too. It’s about 48 km/second (30 miles/second.) Compare this to Mars, with an orbital velocity of only 24 km/second (15 miles/second.) That means that it takes a lot of energy to reach a transfer orbit. And since Mercury has almost no atmosphere, an aero-braking maneuver to enter orbit is out of the question.

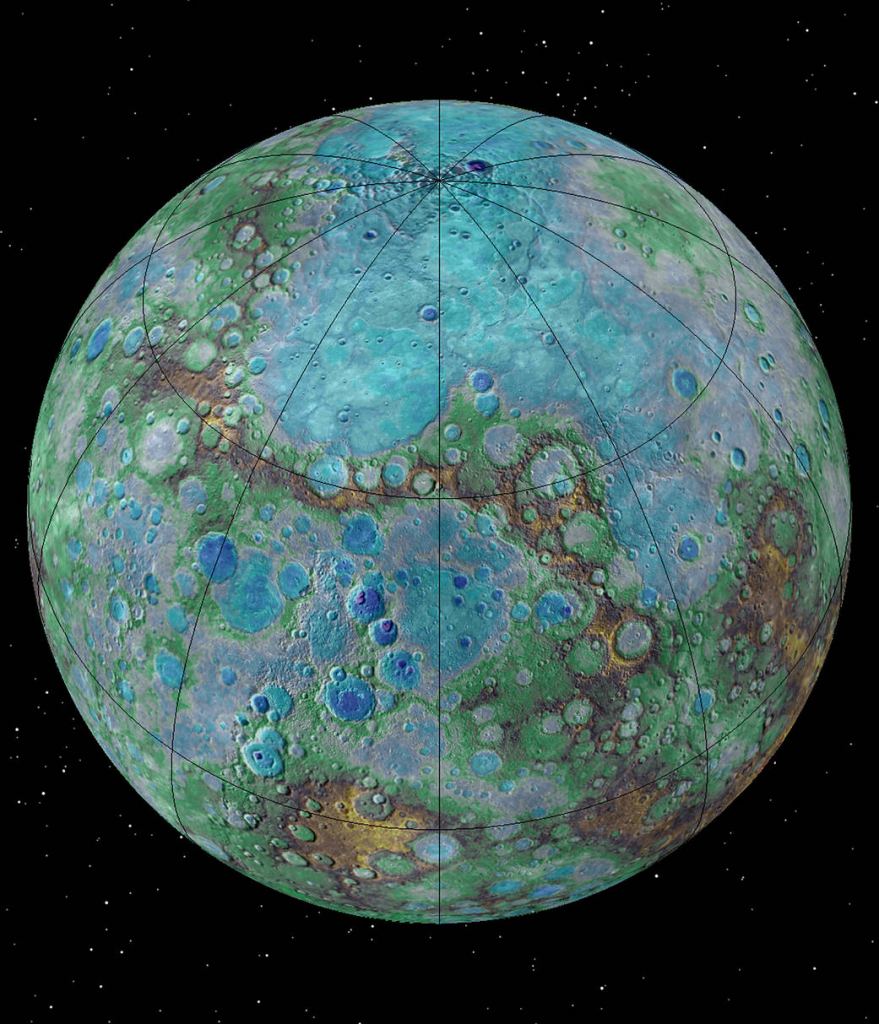

NASA’s Mariner 10 and MESSENGER spacecraft have both visited Mercury. Mariner 10 didn’t really orbit the planet, but performed three pretty close fly-bys. It showed us that Mercury had a heavily cratered surface, much like the Moon. Previously, this detail was hidden from ground telescopes.

Then came NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft. It entered an elliptical orbit around Mercury that gave the spacecraft three quick fly-bys. It was the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury. A main goal of the MESSENGER mission was to image the side of the planet that Mariner 10 couldn’t see. MESSENGER captured almost 100,000 images of Mercury, compared to Mariner 10, which captured fewer than 10,000.

The next spacecraft to visit Mercury will BepiColombo. BepiColombo is a joint mission between the ESA and JAXA. It launched in 2018 and will reach Mercury in 2025. It’s actually two orbiters: a magnetometer probe that will enter an elliptical orbit, and a mapping probe with rockets to put it into a circular orbit.

Every time we grow our understanding of our own Solar System, the more we can understand distant solar systems. There’ll be links between what we observe in Mercury’s transits of the Sun, and what we find out from our probes. Our experience of observing Mercury, then visiting it, will no doubt teach astronomers something about what we can expect to find in other solar systems.

Great stuff, thanks. When I was a kid I craved more visual details about the solar system but we didn’t have the tech. Now watching a Mercury transit is easy. Amazing. Also interesting how it seemed to cross quite close to the sun’s equator.