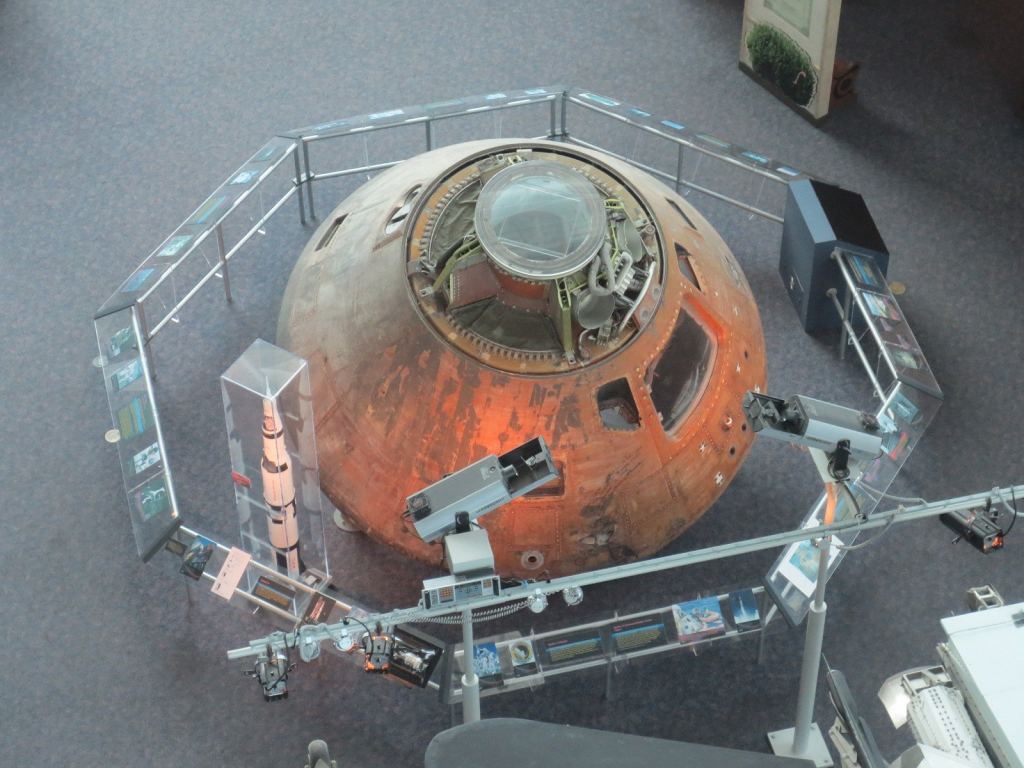

The 50thanniversary of Apollo 11 was a huge celebration, and Apollo 13 may be an equally big commotion. Apollo 12 is tough sell in the middle. Even the Virginia Air & Space Center, which houses the Apollo 12 capsule, uses photographs of Apollo 11 to advertise. Ouch.

This unique mission and its important contribution to science was no less an accomplishment than its famous predecessor or tragic follower, and it pains many to see them become the "lost" journey between two better-known missions, with no movie to dramatize the details of their voyage.

Granted, the mission parameters of Apollo 12, from lunar landing to splashdown were less, well, splashy. The only anxious moments came during launch, which Richard Nixon witnessed, marking the only time a President saw a Saturn V blast off from Cape Kennedy.

36 seconds after liftoff on November 14, 1969 (coincidentally astronaut Fred Haise's birthday), launch control lost telemetry contact at 36.5 seconds due to a lightning strike. While visible to what must have become a shocked crowd at the launch site, the first stage of the booster continued to fire. Yet another lightning strike occurred at the 52-second mark of Apollo 12’s climb into Earth-parking orbit; this one took fuel cells offline, putting the Command Service Module on battery power. Attitude indicators and inverters malfunctioned, lighting up nearly every alarm on the panels. Controllers advised Alan Bean how to get systems back online to avoid a mission abort. Incredibly, later checks showed no damage to spacecraft electrical systems. There was no way to verify possible landing pyrotechnics damage, but the decision (one that Mission Control might be too risk-averse to try today) was made to continue to the Moon. After that, departure from Earth orbit, translunar injection, and translunar coast went by-the-book, and were all but technically indistinguishable from Apollo 11.

On November 19th, Commander Pete Conrad (then aged 39) and Lunar Pilot Alan Bean (37) rode the LM-6 Intrepid to Oceanus Procellarum ("Ocean of Storms") where Conrad put the third set of boots on regolith, humorously reporting to Mission Control: "Whoopee! Man, that may have been a small step for Neil, but that's a long one for me." Shorter legs, it seems.

As a team, Conrad & Bean were known to be a bit less serious than Armstrong & Aldrin (I won't describe the Playboy hijinks here, but you can Google it if you like), and with the initial nail-biting nature of lunar mysteries answered, the second Moon mission was a livelier affair. Pete Conrad later admitted, "We giggled and laughed so much that people accused us of being drunk or having 'space rapture.'"

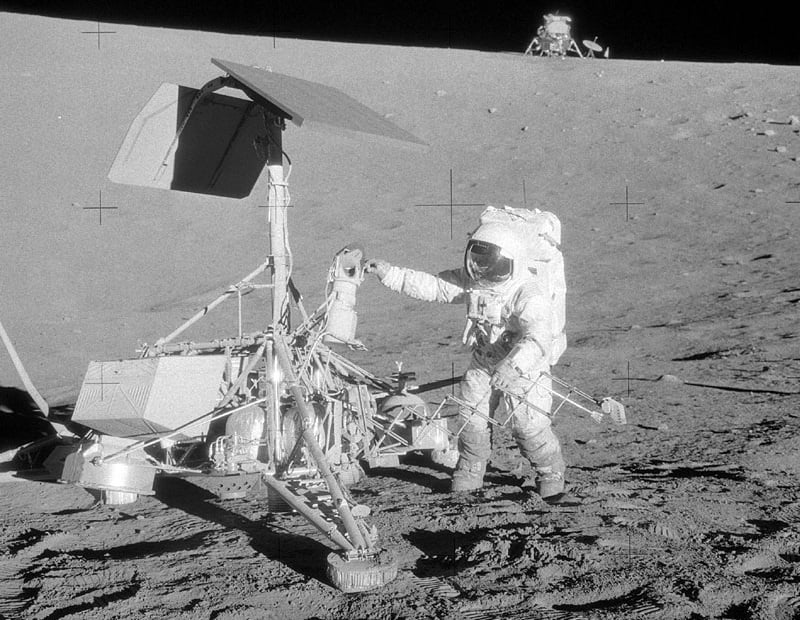

Nonetheless, they planted an American flag, set up a spectrometer to measure the composition of solar wind, and deployed the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), the first nuclear-powered geophysical station on our Moon, using a SNAP-27 atomic generator. This particular set held the first lunar seismometer (whereupon they proved the existence of moonquakes). Over their nearly 32 hours on the Moon, they collected 76 pounds (about 34 kg) of rock samples – 28 more pounds than Apollo 11.

Other surface activities included soil mechanics, structural deduction about the Moon's interior, measurement of the Moon's magnetic field, a cold cathode-gauging of gases in the lunar atmosphere, and a suprathermal detector to measure the lunar ionosphere.

Meanwhile, Command Service Module pilot Dick Gordon (40) remained inside the CSM-108 Yankee Clipper, orbiting the Moon and taking photographs of potential future landing sites for subsequent Apollo missions. After Conrad and Bean rejoined him in lunar orbit, their LM ascent stage was remotely guided to deliberately impact the Moon to provide an actual seismic event that would be picked up by the experiment left behind at the descent stage site. That and many other operational experiments returned data to Earth until 1977.

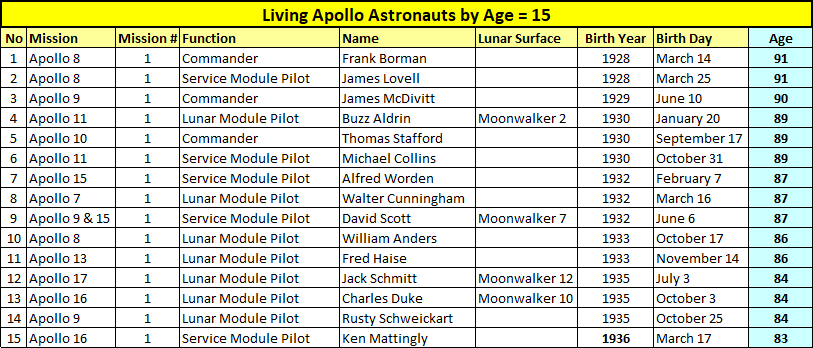

I keep precise statistics on Apollo missions and astronauts and update them each time something changes. Translation: I update them each time someone passes away. As of May 2018, Apollo 12 became one of three missions that now have no crew members left to interview. It has officially passed out of living memory with the men who experienced it firsthand.

Pete Conrad died in a motorcycle accident in Ojai, Ventura County, California. Chumash tribes were the early inhabitants of the Ojai Valley, and in a strange coincidence, "Ojai," originally spelled 'Awha'y in Ventureño, is the Chumash Native American word for Moon. He was 69 years old. CSM pilot Dick Gordon died of cancer in 2017 at age 88. Alan Bean died of sudden illness in 2018 at age 86.

Apollo Missions with all 3 crew members = 8, 9Apollo Missions with 2 remaining crew members = 7, 11, 13, 15, 16Apollo Missions with 1 remaining crew member = 17, 10Apollo Missions with 0 living crew members = 1, 12, 14Four astronauts completed TWO Apollo missions:Lovell (8 & 13), Scott (9 & 15), Young (10 & 16), Cernan (10 & 17)

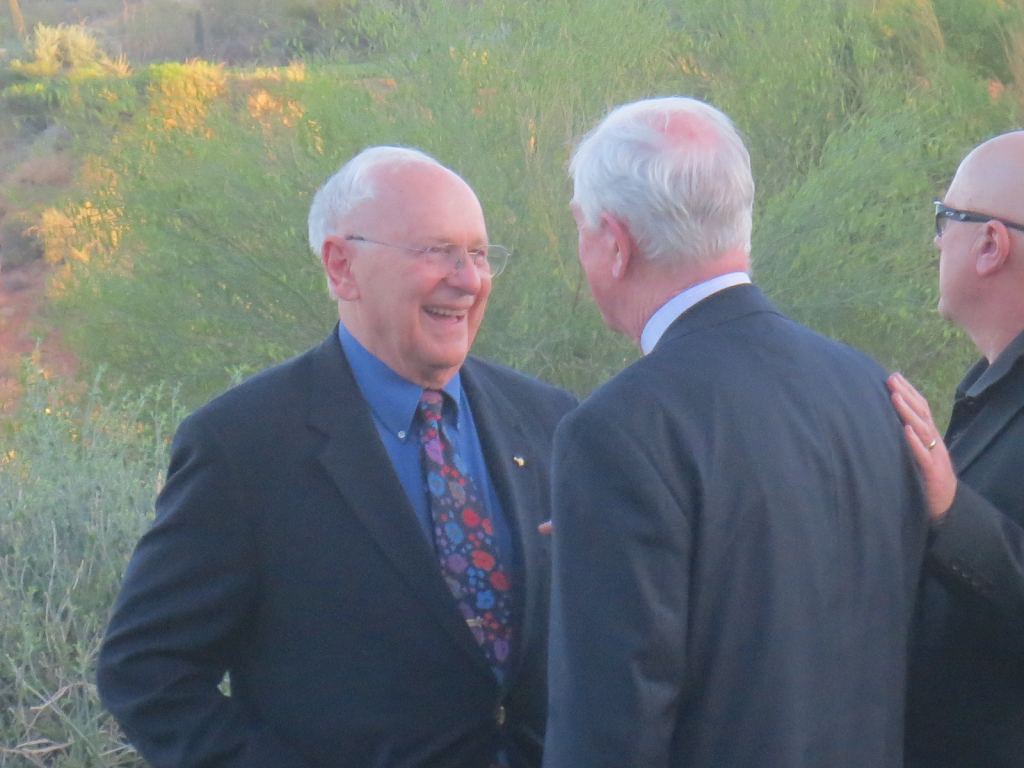

The NASA family and space enthusiasts across social media platforms were keenly aware of what had been lost, though one wonders what the general public made of the last crew member death, if it even registered at all. Would most people even know an Apollo astronaut in line at the post office if they saw one? I remember attending SpaceFest in Tucson, Arizona and marveling that I watched Fred Haise pick up coffee from the convention center Starbucks entirely unaccosted, and how Alan Bean moseyed through the hotel lobby, drawing no reaction whatsoever. It was disturbing to think, "If Justin Bieber tangoed through here, there would be a fuss. These Moonwalkers *risked their lives for science*, and no one even recognizes them."

During panels and autograph sessions in their decorated booths, many were conscious of "how they were supposed to act like heroes," but it's clear they didn't always adore one another. If you spend any time around Right-Stuff-era astronauts, you see the "once a flyboy always a flyboy" idiom in action. What made them great test pilots didn't always create the best setting for teamwork. Conrad and Gordon had flown together previously on the Gemini V mission, where Conrad facetiously referred to their dual capsule as a "flying garbage can." They were famously photographed grinning at one another many times, and one hopes shared hardships forged friendships, given how often they would be thrown together for PR events over a lifetime.

However, while attending an Apollo themed luncheon at the same conference, Gordon quipped humorously, if somewhat inappropriately in front of the children after one asked him if he was lonely in his orbiting capsule, "Nah. If you knew Alan Bean and Pete Conrad, you'd be glad to get rid of 'em!" The kids laughed. But I wondered just what kind of shenanigans had gone down in the Mobile Quarantine Facility following their splashdown to Earth on November 24, 1969. There was no getting rid of one another in the Airstream trailer!

Buzz Aldrin has long been a one-man public relations parade float, and Michael Collins recently joined Twitter to offer stories to a new generation of people who were not alive in 1969 to see his work. Dozens of Apollo and Shuttle astronauts attend conferences and NASA center events each year to interact with the public. For Apollo 1, 12, and 14, there is no one left to speak for their missions.

Project Apollo spanned the years 1961 to 1975, and to this day, stands alone in achieving crewed missions beyond low Earth orbit (LEO); it is also the lone space program to provide a habitat for Earthlings to orbit or work in the lunar environment. All who did so are now octogenarians or nonagenarians.

Their missions led to technological leaps in rocketry, avionics, computer chips, telecommunications, and "life support" in lifeless environments. The collective work of thousands across the civil and engineering fields made Project Apollo one of the greatest feats of humankind. It was miraculous then, and it's still mind-blowing now, despite how blasé people have become with a "been there, done that" mind-set, in an age where the average iPhone contains more memory than the (now hilariously low-tech) Apollo Guidance Computers.

BIOGRAPHY

Heather Archuletta is from San Francisco, and has degrees from Mills College and the University of London. After working in the tech industry for 17 years, she joined a NASA space flight simulations program which studies the long-term effects of weightlessness on astronauts. Her " Pillow Astronaut " blog, which describes the flight sims in detail, has been featured in Wired, Popular Science, and FOX in America, as well as news outlets in Europe, India, Scandinavia, and Russia. Heather has been featured previously in Universe Today, in Go to Bed for NASA (2009) and Awesome Map of Space Agencies Around the World (2012).

Universe Today

Universe Today