Since the turn of the century, space exploration has changed dramatically thanks to the unprecedented rise of commercial aerospace (aka. NewSpace). With the goal of leveraging new technologies and lowering the costs of launching payloads into space, some truly innovative and novel ideas are being put forth. This includes the idea of using balloons to carry rockets to very high-altitudes, then firing the payloads to their desired orbits.

Also known as "Rockoons", this concept has informed Leo Aerospace 's fully-autonomous and fully-reusable launch system - which consists of a high-altitude aerostat (balloon) and a rocket launch platform. With the first commercial launches slated for next year, the company plans to use this system to provide regular launch services to the microsatellite (aka. CubeSat) market in the coming years.

The concept of the Rockoon is one of many air-launch-systems that have been investigated and validated since the Space Age began. Unlike conventional rockets, which rely on massive amounts of propellant to achieve escape velocity and send payloads to orbit, air-launch-systems rely on the comparatively cost-effective method of transporting a payload to high altitude where it can then be sent to Low Earth Orbit (LEO).

This reduces the amount of propellant needed but also involves launching a rocket from altitudes where air resistance is lower and less force is needed to escape Earth's gravity. All of this allows for much smaller and lighter launch vehicles to be used, which leads to significantly reduced costs. This method is especially effective when it comes to small payloads like microsatellites, which are becoming all the more common.

Today, most air-launch-systems that are being pursued involve aircraft bringing rockets or spacecraft with rocket motors to launch altitudes - such as Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo, Virgin Orbit's LauncherOne, or the Stratolaunch air carrier. However, the Los Angeles-based Leo Aerospace company chose to investigate the equally valid method of relying on a lighter-than-air (LTA) platform to get payloads to space.

As Dane Rudy, co-founder and CEO of Leo Aerospace, told Universe Today via email:

"From a first-order physics perspective, balloon launch is a very elegant solution to providing an efficient and cost-effective launch for small payloads. Additionally, this architecture dramatically reduces the amount of launch infrastructure required, enabling a fully mobile solution."

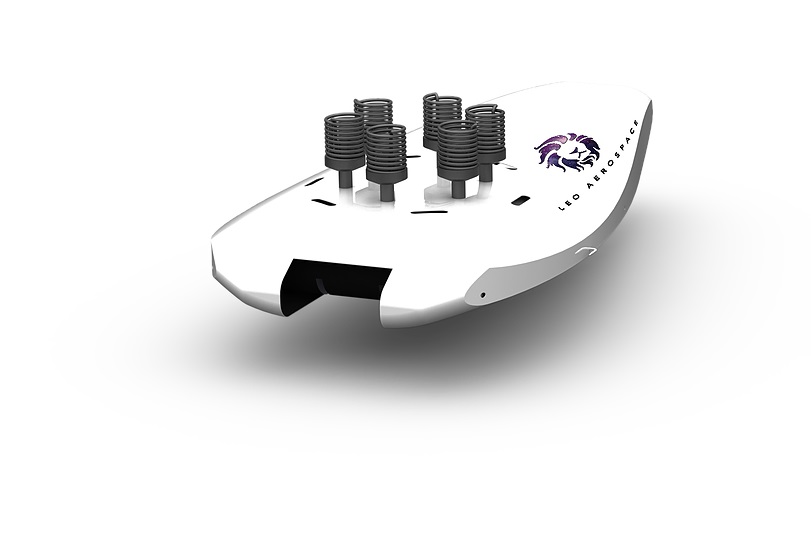

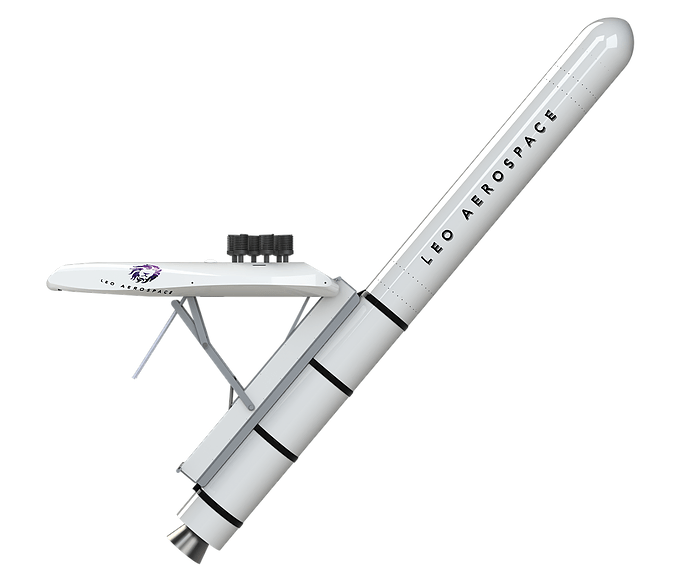

The central components of this launch system are the Regulus Orbital launch platform and the Orbital Rocket. The Regulus platform provides autonomous flight control through a series of burners (which ensure that the aerostat remains buoyant) and a rotational control system of bipropellant thrusters, all of which are mounted to an insulated body composed of composite material.

Meanwhile, the Orbital Rocket is a miniature three-stage launch vehicle that is attached to the platform via an actuator and a launch rail. Once the aerostat reaches a deployment altitude of 18,000 meters (60,000 ft), the rocket will launch and carry the payload to its desired orbit. According to the company's mission profiles page, the system will be capable of conducting multiple types of deliveries to different altitudes.

"The development and production cost of a balloon system is orders of magnitude less than using an airplane," said Rudy. "Compared to other balloon systems that use lifting gas, our hot-air architecture is fully and rapidly reusable. We can conduct dozens of launches with a single system before refurbishments are required."

These will range from suborbital missions - where payloads are sent to altitudes over 100 km (62 mi) - to orbital missions, where CubeSats will be sent to sun-synchronous orbit (SSO) of 550 km (340 mi). Another possibility they are sure to mention involves the delivery of humanitarian aid or emergency communications equipment to remote regions that are inaccessible to fixed-wing aircraft, drones, or other aerial vehicles.

The company also plans to incorporate gliders and drones that can deploy from their aerostats, thus offering other mission profiles - such as drone monitoring, scientific experiments, and communications services. In addition to being a more cost-effective means of placing small payloads in orbit, the launch system also has the benefit of being very compact.

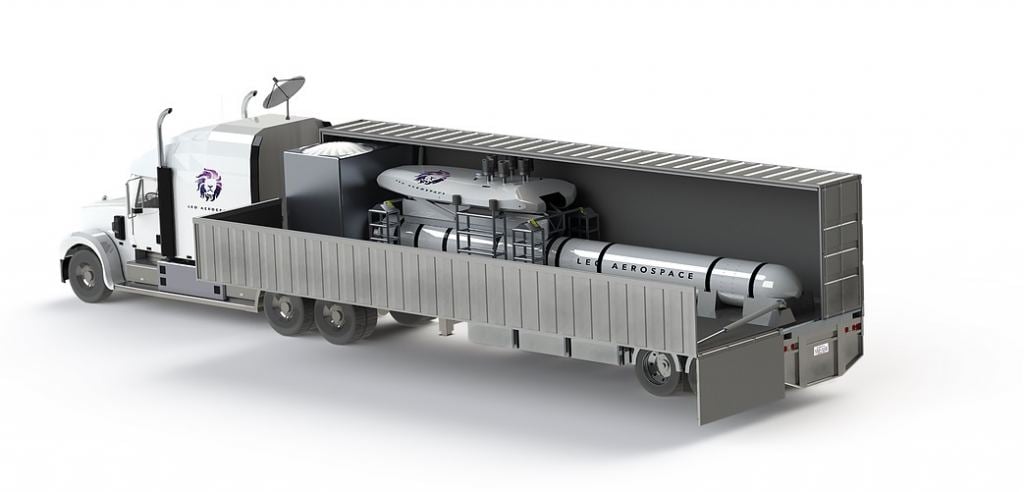

Because of this, the rocket, aerostat, and machinery needed for inflating it can all be placed into a standard shipping container, loaded onto a semi-truck, and then shipped wherever it is needed. The trailer cab also serves as the initial communications station for the launch. This level of mobility and flexibility is one of the characteristics that could make aerostat platforms effective at delivering emergency aid and relief services. As Rudy said:

"We are beginning to uncover many different use cases for the reusable and autonomous aerostat platform that we are developing. It is entirely mobile and fits into a standard shipping container, making it easy to transport and store. Additionally, it is simple to operate and incredibly robust. Unlike lifting gas balloons, our system can still operate with a hole the size of a car in the balloon material. Our collaborators are excited to leverage these capabilities to rapidly deploy sensor suites in disaster areas post-hurricane or provide emergency relief supplies in places that are difficult to reach. It has been incredible to work with groups like the Army Space and High-Altitude Experiments branch to identify and solve such a range of problem cases."

All of this puts companies like Leo Aerospace, and others that are pursuing lighter-than-air concepts, in good stead to take advantage of the growth in the satellite market. Between the proliferation of microsatellites (aka. CubeSats) and the emergence of light-payload launch services (like Rocketlab and Virgin Orbit), this market is expected to explode in the coming years.

What sets Leo Aerospace apart, however, is the way they are focused on the delivery of satellites that weigh less than 25 kg (55lbs). As Rudy explained, there isn't a dedicated solution yet for microsatellites that fall into this range. Typically, CubeSats are forced to "rideshare" on launch rockets, where they take up free space alongside heavier payloads.

This is something that Rudy and his colleagues hope to remedy:

"This is extra surprising given that almost half of all satellites in the next 10 years are projected to fall within this segment. We have worked hard to capture and maintain a first mover advantage in the 25kg segment. We have conducted the most extensive operations and testing of our vehicle. Additionally, we are the furthest in regulatory work through our close relationship with the FAA and active membership in the Commercial Spaceflight Federation. Finally, our system is tailored to provide the dedicated launch that our customers need, and at a high enough frequency to address the incredible demand."

By the end of 2018, the company had successfully completed a launch-test campaign and secured funding through the National Science Foundation and a venture capital firm. In 2020, they hope to fully flight-qualify their platform by conducting their first flight, which will be followed by commercial operations and maybe even contracts with NASA.

"These commercial operations will be our entry into the $2.6B High-Altitude Platform Services market with a range of civil, defense, and commercial customers," said Rudy. "We have been working with NASA JPL to explore several different use cases. One example is carrying Martian entry vehicles into the upper atmosphere here on Earth and dropping them to collect data and test aerodynamic performance."

From its humble beginnings, the full-scale commercialization of space has been progressing by leaps and bounds in recent years. Between declining launch costs, the development of smaller payloads, and the rise of commercial launch providers that can accommodate smaller payloads, Low Earth Orbit (LEO) is likely to become a very busy place in the near future!

Further Reading: *Leo Aerospace*

Universe Today

Universe Today