The Chang’e-4 mission, the fourth installment in the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, has made some significant achievements since it launched in December of 2018. In January of 2019, the mission lander and its Yutu 2 (Jade Rabbit 2) rover became the first robotic explorers to achieve a soft landing on the far side of the Moon. Around the same time, it became the first mission to grow plants on the Moon (with mixed results).

In the latest development, the Netherlands-China Low Frequency Explorer (NCLE) commenced operations after a year of orbiting the Moon. This instrument was mounted on the Queqiao communications satellite and consists of three 5-meter (16.4 ft) long monopole antennas that are sensitive to radio frequencies in the 80 kHz – 80 MHz range. With this instrument now active, Chang’e-4 has now entered into the next phase of its mission.

The radio observatory is the result of collaboration between the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) and the China National Space Agency (CNSA). ASTRON has a long history of conducting radio astronomy, which includes the operation of one of the largest radio telescopes in the world – the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope (WSRT), which is also part of the European Very Long Baseline Interferometry Network (EVN).

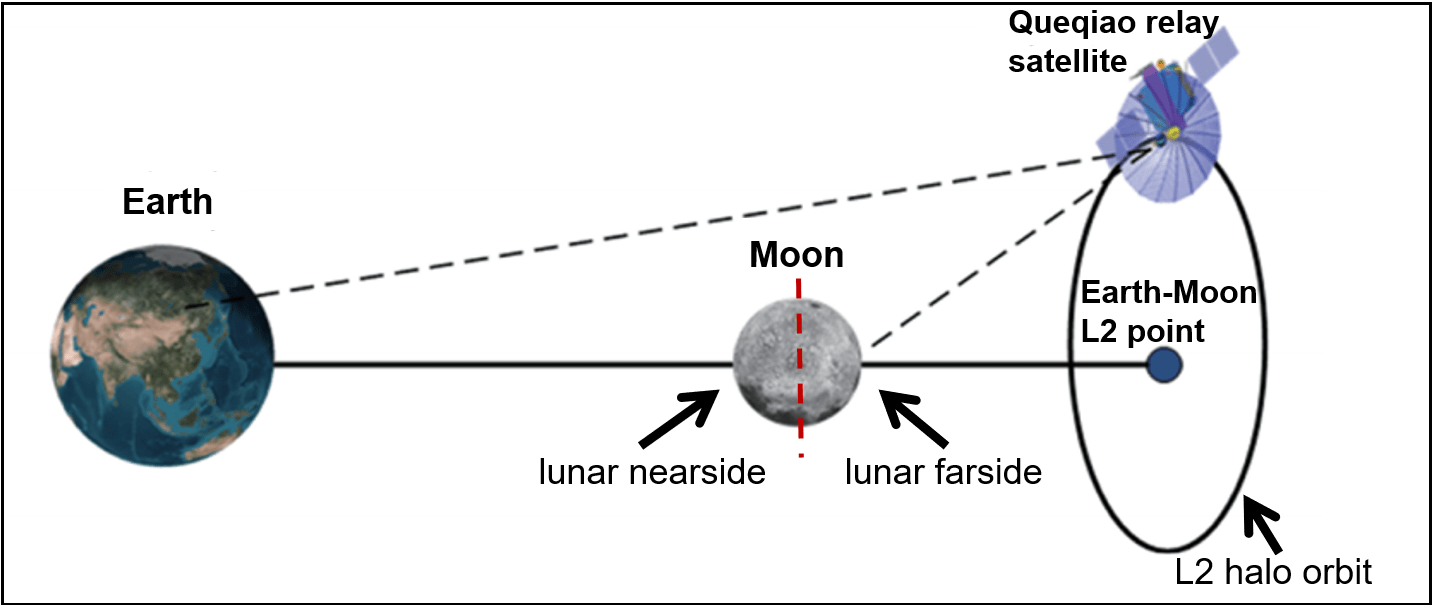

The NCLE is the first observatory built by the Netherlands and China to conduct radio astronomy experiments while orbiting on the far side of the Moon. This location is considered ideal for such experiments since it is removed from any terrestrial radio interference. It is for this reason that Queqiao has had to act as a communications relay with the Chang’e-4 mission since radio signals cannot reach the far side of the Moon directly.

While the NCLE is capable of mounting multiple forms of scientific research, its main purpose is to conduct groundbreaking experiments in radio astronomy. Particularly, the NCLE will gather data in the 21-cm (8.25 inch) emission range, which corresponds with the earliest periods in cosmic history.

These are otherwise known as the Dark Ages and Cosmic Dawn, which have previously been inaccessible to astronomers. By examining light from the earliest periods of the Universe, astronomers will finally be able to answer some of the most enduring questions about the Universe. These include when the first stars and galaxies formed, as well as the influence of Dark Matter and Dark Energy on cosmic evolution.

Until now, the Queqiao satellite was primarily a communications relay between the lander and rover and mission controllers on Earth. But with the primary goals of the Chang’e-4 mission now achieved, the China National Space Agency (CNSA) has entered into the next phase of operations, which is to operate a radio observatory on the far side of the Moon.

As Marc Klein Wolt, the Managing Director of the Radboud Radio Lab and leader of the Dutch team, expressed:

“Our contribution to the Chinese Chang’e 4 mission has now increased tremendously. We have the opportunity to perform our observations during the fourteen-day-long night behind the moon, which is much longer than was originally the idea. The moon night is ours, now.“

The unfolding of the antennas is the culmination of three years of hard work and the demonstration of this technology is expected to pave the way for new opportunities for radio instruments in space. In addition to scientists with ASTRON and the CNSA, there is no shortage of people around the world who are eagerly awaiting the NCLE’s first radio measurements.

Professor Heino Falcke, the chair of astrophysics and radio astronomy at Radboud University, is also the scientific leader of the Dutch-Chinese radio telescope. As he explained:

“We are finally in business and have a radio-astronomy instrument of Dutch origin in space. The team has worked incredibly hard, and the first data will reveal how well the instrument truly performs.”

The deployment of the instrument was meant to happen sooner and the year-long wait behind the Moon is believed to have had an effect on the antennas. Initially, the antennas unfolded smoothly but the progress became increasingly sluggish as time went on. As a result, the team decided to collect data first from the partially-deployed antennas first and may decide to unfold them further later.

At their current, shorter deployment, the instrument is sensitive to signals from roughly 13 billion years ago – aka. about 800 million years after the Big Bang. Once the antennas are unfolded to their full length, they will be able to capture signals from just after the Big Bang. This will allow astronomers to see the first stars being born and star clusters coming together to form the very first galaxies.

The first light in the Universe and the answers to some of the most profound questions will finally be accessible!

Further Reading: Radboud University