Stars are formed within large clouds of gas and dust known as stellar nurseries. While star formation was once seen as a simple gravitational process, we now know it is a complex dance of interactions. When one star forms it can send shock waves through the interstellar medium that trigger other stars to form. Supernovae and galactic collisions can trigger the creation of stars as well. One way to study stellar formation is to look at where stars form within a galaxy.

In some regions of our galaxy, such as the Orion Nebula, stars are actively forming. We can see stellar nurseries in action. But on a cosmic scale, these star-forming regions tend to fizzle out fairly quickly. So astronomers also look at the distribution of OB stars. These are massive, bright stars with short lifetimes. Because these stars only live for about a million years, they don't have time to wander far from their place of birth. And because they are very bright they are easy to observe.

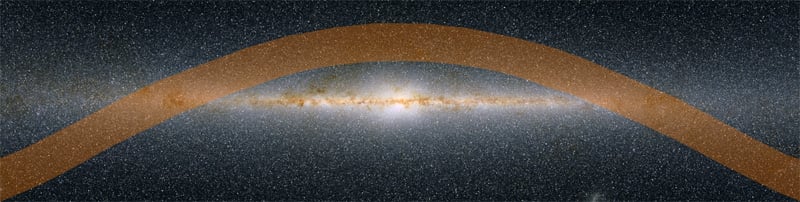

In the late 1800s, astronomer Benjamin Gould studied OB stars and found that many of them lie within a partial ring within our galaxy, titled about 20 degrees from the plane of the Milky Way. It came to be known as the Gould Belt. We are within this region of the Milky Way, which is one of the reasons there are so many bright stars in the night sky.

It isn't clear what could have caused the Gould belt, but one idea is that a cluster of dark matter collided with molecular gas clouds in our galaxy. Similar star-forming belts are seen in other galaxies, so it was thought that this kind of dark matter collision could be a trigger.

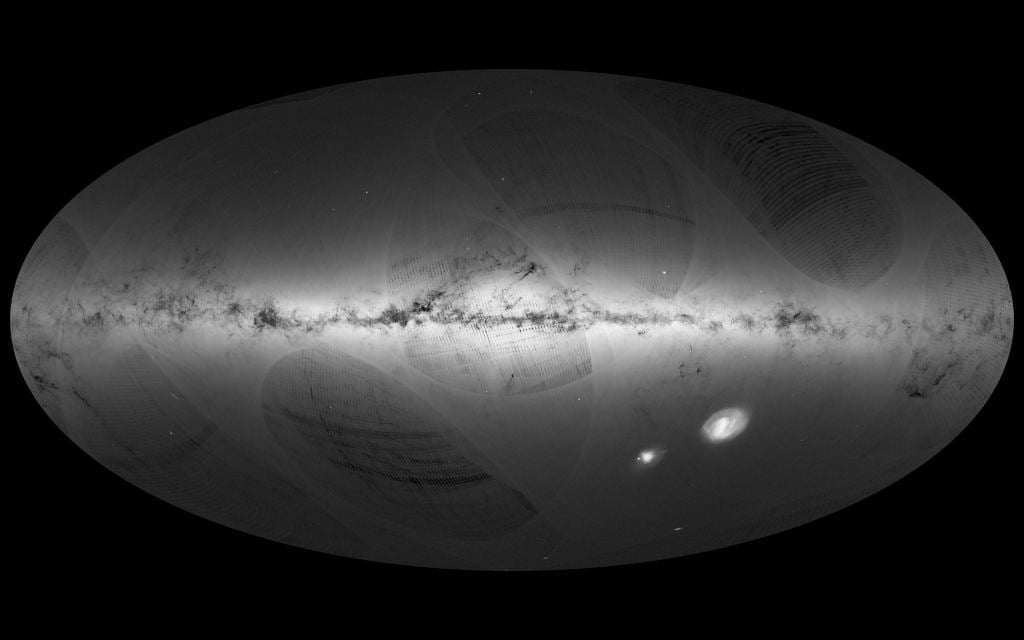

But once again we're beginning to learn that things aren't quite so simple. Recently a team looked at data gathered from the Gaia spacecraft to make a detailed map of the position and motion of bright stars in the Gould Belt regions. From this, they created a 3-D map of interstellar gas and dust. They found that rather than being arranged in a ring structure, the stellar nurseries followed a narrow region that follows a sinusoidal curve. It is about 9,000 light-years across, and rises and falls about 500 light-years above and below the galactic plane.

This complex structure throws shade on the idea that Gould's Belt exists at all. Its appearance could just be due to our view of this wave structure. It isn't clear what formed this filament structure, but it does resemble a kind of ripple effect as if something collided with our galaxy.

Detailed surveys such as those gathered Gaia are still in the relatively early stages. We're only beginning to create truly accurate maps of our galaxy. These new maps will certainly have much to teach us in the coming years.

Source: Alves, J., Zucker, C., Goodman, A.A. et al. " A Galactic-scale gas wave in the solar neighborhood " Nature (2020)

Universe Today

Universe Today