Located at the heart of the NASA Center for Climate Simulation (NCCS) - part of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center - is the Discover supercomputer, a 129,000-core cluster of Linux-based processors. This supercomputer, which is capable of conducting 6.8 petaflops (6.8 trillion) operations per second, is tasked with running sophisticated climate models to predict what Earth's climate will look like in the future.

However, the NCCS has also started to dedicate some of Discover's supercomputing power to predict what conditions might be like on any of the over 4,000 planets that have been discovered beyond our Solar System. Not only have these simulations shown that many of these planets could be habitable, they are further evidence that our very notions of "habitability" could use a rethink.

Despite the sheer number of exoplanet discoveries that have taken place in the past decade or so, scientists are still forced to rely on climate models to determine which among them could be "potentially habitable." At present, exploring these planets via spacecraft is entirely impractical because of the sheer distances involved.

As we addressed in a previous article, it would take roughly 19,000 and 81,000 years to reach the nearest star system (Alpha Centauri) using current technology. In addition, direct observation of exoplanets is only possible in rare cases using today's telescopes, which typically involves massive planets that orbit their stars at a great distance. These planets tend to be gas giants and are therefore not candidates for habitability.

In any case, astronomers have found that all the planets observed beyond our Solar System are pretty eclectic in nature. For the most part, the 4,108 exoplanets that have been confirmed to date have either been Neptune-like gas giants (1375), Jupiter-like gas giants (1293), or Super-Earths (1273). Only 161 exoplanets have been terrestrial (aka. rocky or "Earth-like") in nature, all of them found around M-type (red dwarf) stars.

As Elisa Quintana - a NASA Goddard astrophysicist who led the team responsible for the 2014 discovery of Kepler-186f, the first Earth-sized planet in a habitable zone (HZ) - explained:

“For a long time, scientists were really focused on finding Sun- and Earth-like systems. That’s all we knew. But we found out that there’s this whole crazy diversity in planets. We found planets as small as the Moon. We found giant planets. And we found some that orbit tiny stars, giant stars and multiple stars.”

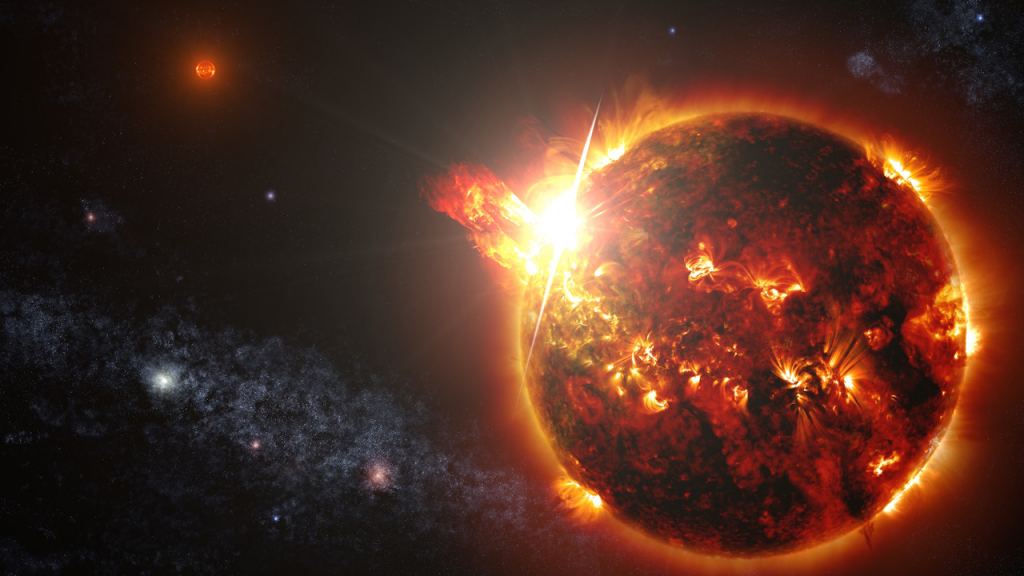

The discovery of terrestrial planets that orbit within the HZs of red dwarfs was initially a source of great excitement. Not only are these stars the most common in our Universe - accounting for 85% of stars in the Milky Way alone - but several have been found to orbit stars that are close to the Solar System.

This includes the three planets that orbit within the HZ of TRAPPIST-1 (39.46 light-years away) and Proxima b, the closest exoplanet to Earth (4.24 light-years away). Unfortunately, numerous studies have been conducted in recent years that have indicated that these planets would have difficulty maintaining a viable atmosphere over time.

To put it simply, the fact that they are smaller and cooler means that red dwarfs have HZs that are much closer to their surfaces. This means that any planet orbiting with a red dwarf's HZ is likely to be tidally locked with them, which means one side is constantly facing towards the star and on the receiving end of all the star's heat, radiation, and solar wind.

Whether or not these planets could be habitable depends on many factors, such as the presence of a dense atmosphere, a magnetosphere, and the proper chemical abundances. In lieu of seeing planets directly and ascertaining these ingredients for life (aka. biosignatures) exist, scientists rely on climate models to aid in the search for "potentially habitable" exoplanets.

According to Karl Stapelfeldt, NASA's chief exoplanetary scientist based at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the ability to model the climates on other planets is absolutely essential to the future of space exploration. "The models make specific, testable predictions of what we should see," he said. "These are very important for designing our future telescopes and observing strategies."

Put simply, climate modeling involves creating a simulation of what Earth's (or another planet's) climate will be like based on specific conditions and/or environmental change. For years, this work was performed by Anthony Del Genio, a recently-retired planetary climate scientist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies. During his career, Del Genio conducted climate simulations involving Earth and other planets (including Proxima b).

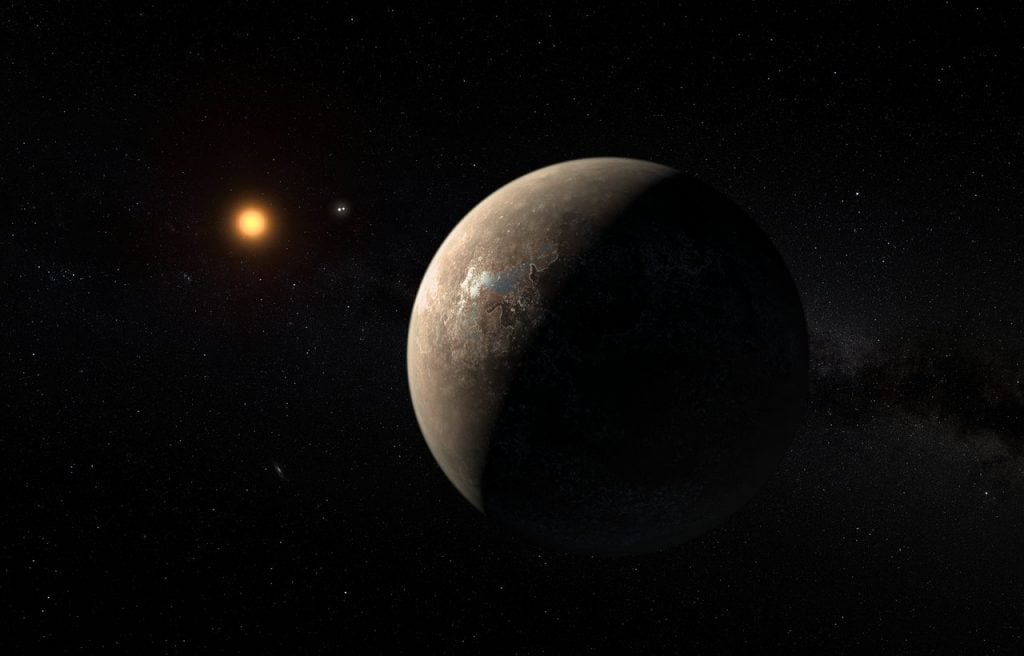

To recap, Proxima b is roughly the same size as Earth and at least 1.3 times as massive. It orbits its star (Proxima Centauri) once every 11.2 Earth days and at a distance of 0.05 AU (5% the distance between the Earth and the Sun). At this distance, the planet is likely to be gravitationally locked to its star, with one side constantly exposed to the star's intense radiation. At the same time, the other is subjected to constant darkness and freezing temperatures.

However, Del Genio's team recently simulated possible climates on Proxima b yet again to see how many would result in a warm and wet environment capable of supporting life. Interestingly enough, these simulations showed that planets like Proxima b could be habitable despite being tidally locked with one side exposed to heavy amounts of radiation.

To conduct these simulations, Del Genio's team used the Discover supercomputer to run a planetary simulator that they developed themselves - called ROCKE-3D. This simulator is based on a version of the Earth climate model that was first developed in the 1970s that they upgraded to simulate climates on other planets, based in part on the kinds of orbits they might have and their atmospheric compositions.

For each simulation, Del Genio's team varied the conditions on Proxima b to see how it would affect its climate. This included adjusting the types and amounts of greenhouses gases in its atmosphere, the depth, size, and salinity of its oceans, and the ratio of land to water. From this, they were able to see how clouds and oceans would circulate and how radiation from the planet's Sun would interact with Proxima b's atmosphere and surface.

They found that Proxima b's hypothetical cloud layer would act as a shield, deflecting the Sun's radiation from the surface and lowering the temperature on Proxima b's sun-facing side. This is consistent with research conducted by scientists with the Sellers Exoplanet Environments Collaboration (SEEC) at NASA Goddard that showed how Proxima b could form clouds so massive that they would cover the entire sky.

As Ravi Kopparapu, a NASA Goddard planetary scientist who also models the potential climates of exoplanets, explained it:

“If a planet is gravitationally locked and rotating slowly on its axis a circle of clouds forms in front of the star, always pointing towards it. This is due to force known as the Coriolis effect, which causes convection at the location where the star is heating the atmosphere. Our modeling shows that Proxima b could look like this.”

Along with ocean circulation, this circle of clouds would also mean that warm air and water can move to Proxima b's dark side, thereby achieving heat transfer and making the entire planet more hospitable. "So you not only keep the atmosphere on the night side from freezing out, you create parts on the night side that maintain liquid water on the surface, even though those parts see no light," said Del Genio.

In addition to circulating and maintaining heat, atmospheres and ocean currents are also responsible for distributing gases and chemical elements necessary for life as we know it - e.g., oxygen gas, carbon dioxide, methane, etc. These are known as "biosignatures" since they are essential to life here on Earth or are associated with biological processes.

However, "as we know it" is the keyword here. At present, Earth remains the only known habitable planet, and the various life forms it supports are the only examples we are familiar with. As such, looking for life beyond Earth is currently limited to searching for biosignatures that are necessary for (and associated with known) lifeforms. This is what we call the "low-hanging fruit approach."

What's more, Earth has evolved considerably over the last few billion years, as have the lifeforms that have called it home. While oxygen gas is essential for mammalian creatures today, it would have been toxic to photosynthetic bacteria that thrived in a predominantly carbon dioxide and nitrogen gas atmosphere that existed on Earth billions of years ago.

So while this kind of modeling cannot say for certain if a planet is inhabited, it certainly can help narrow the search by showing which candidates are promising targets for follow-up observations. "While our work can't tell observers if any planet is habitable or not, we can tell them whether a planet is smack in the midrange of good candidates to search further," said Del Genio.

This will be especially helpful in the coming years when next-generation telescopes take to space. These include the James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in 2021, and the Wide-Field Infrared Space Telescope (WFIRST), which will launch in 2023. Along with ground-based observatories like the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), these instruments will allow scientists to directly observe smaller planets for the first time.

Coronographs like the Starshade will also make a big difference by drowning out the light from stars, which otherwise obscures light reflected from a planet's atmosphere. These and other developments mean that astronomers will be able to study the atmospheres of rocky exoplanets as well, which will allow them to finally say with confidence which planets are "potentially habitable."

Be sure to check out this animation of what Proxima b's climate might look like, courtesy of Del Genio's team and the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center:

*Further Reading: NASA*

Universe Today

Universe Today