NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope has reached the end of its life. Its mission was to study objects in the infrared, and it excelled at that since it was launched in 2003. But every mission has an end, and on January 30th 2020, Spitzer shut down.

"Its immense impact on science certainly will last well beyond the end of its mission." NASA Associate Administrator Thomas Zurbuchen

Thinkers have been grappling with the nature of light for an awfully long time. Back in Ancient Greece, Aristotle wondered about light and said, "The essence of light is white light. Colors are made up of a mixture of lightness and darkness." That was the extent of our understanding of light back then.

Isaac Newton wondered about light, too, and said "Light is composed of colored particles." In the early 19th century, English physicist Thomas Young provided evidence that light behaves like a wave. Then came Maxwell, Einstein, and others who all thought deeply about light. It was Maxwell who figured out that light itself is an electromagnetic wave.

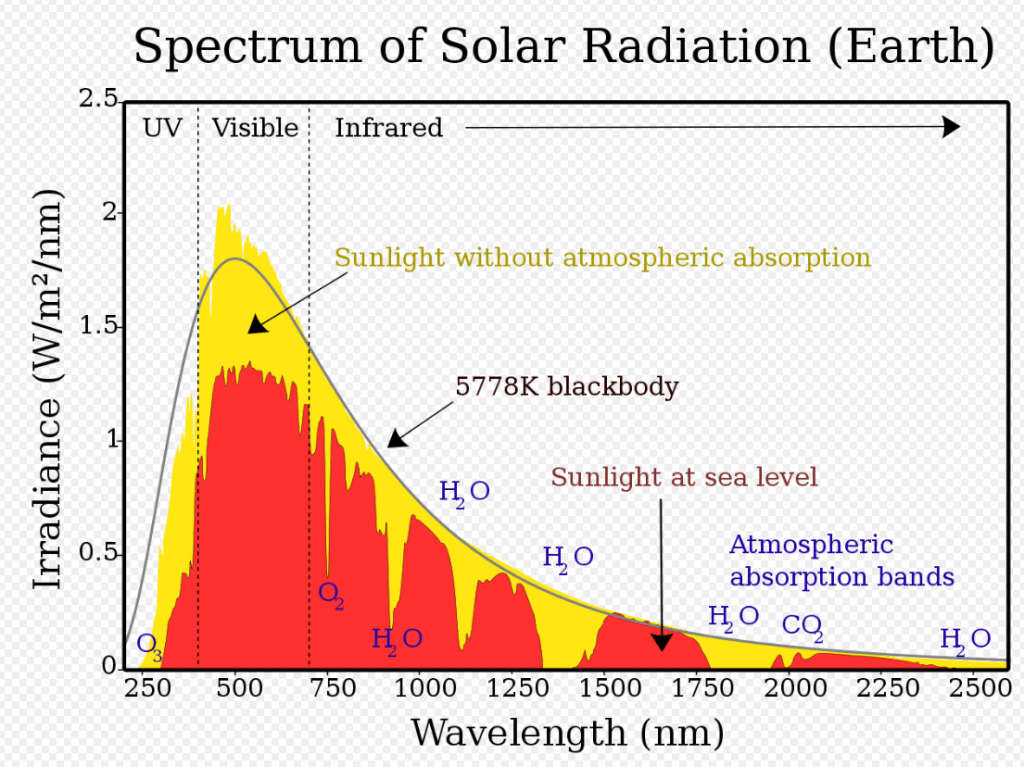

But it was the astronomer William Herschel, well-known as the discoverer of Uranus, who discovered infrared radiation. He also pioneered the field of astronomical spectrophotometry. Herschel used a prism to split light, and with a thermometer he discovered unseen light that heated things up.

Eventually, scientists found that half of the light from the Sun is infrared light. It became clear that to understand the cosmos around us, we needed to understand infrared light, and what it can tell us about the objects emitting it.

So infrared astronomy was born. All objects emit some degree of infrared radiation, and in the 1830s the field of infrared astronomy got going. But not much progress was made at first.

At least, not until the early 20th century. That's when objects in space were discovered solely by observing in the infrared. Then radio astronomy took off in the 1950s and 1960s, and astronomers realized that there was a lot to be learned about the universe, outside of what visible light can tell us.

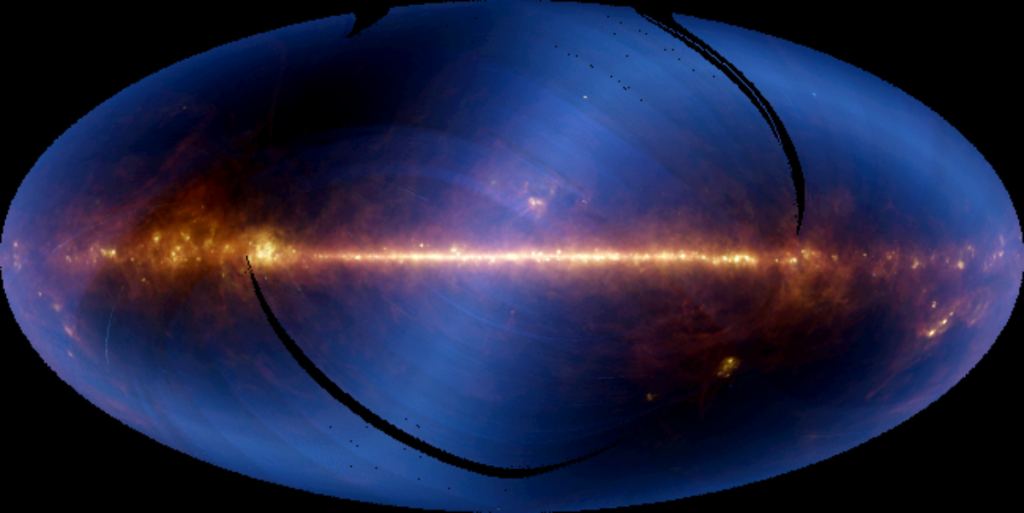

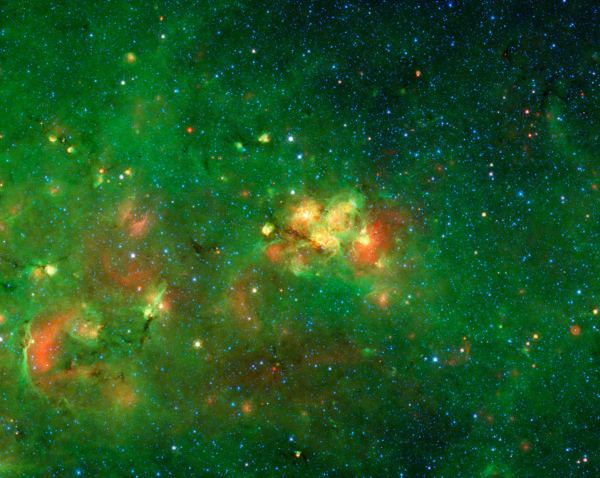

Infrared astronomy is powerful because it allows us to see through gas and dust, into places like the core of the Milky Way galaxy. But observing in the infrared is difficult for ground-based facilities. The Earth's atmosphere gets in the way. Infrared ground observations mean long exposure times, and contending with the heat given off by everything, including the telescope itself. An orbital observatory was the solution, and two were launched: the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) and the Infrared Space Observatory (ISO).

In 1983, the UK, the US, and the Netherlands launched IRAS, the Infrared Astronomical Satellite. It was the first infrared space telescope, and though it was a success, its mission lasted only 10 months. Infrared telescopes need to be cooled, an IRAS's supply of coolant ran out after 10 months.

IRAS was a successful, though short-lived, mission, and the astronomy community realized that without a dedicated infrared observatory, efforts to understand the universe would be hampered. IRAS surveyed almost the entire sky (96%) four times. Among other accomplishments, IRAS gave us our first image of the Milky Way's core.

Then the ESA launched the ISO (Infrared Space Observatory) in 1995, and it lasted three years. One of its accomplishments was determining the chemical components in the atmospheres of some of the Solar System's planets. It also found several protoplanetary disks, among other achievements.

But there was a need for more infrared astronomy, and NASA had an ambitious project in mind: the Great Observatories program. The Great Observatories program saw four separate space telescopes launched between 1990 and 2003:

- The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) was launched in 1990 and observes mostly in optical light and near-ultraviolet.

- The Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory (CGRO) was launched in 1991 and observed mostly gamma rays, and some x-rays as well. Its mission ended in 2000.

- The Chandra X-Ray Observatory (CXO) primarily observes soft s-rays, and its mission is ongoing.

- The Spitzer Space Telescope.

Together, they observed across a wide swath of the electromagnetic spectrum. The space telescopes were synergistic, and they often observed the same targets to capture a complete energetic portrait of objects of interest. (There's no radio astronomy space telescope because radio waves are easily observed from Earth's surface. And radio-telescopes are massive.)

The Spitzer was launched on August 25th 2003 on a Delta II rocket from Cape Canaveral. It was placed into a heliocentric, Earth-trailing orbit.

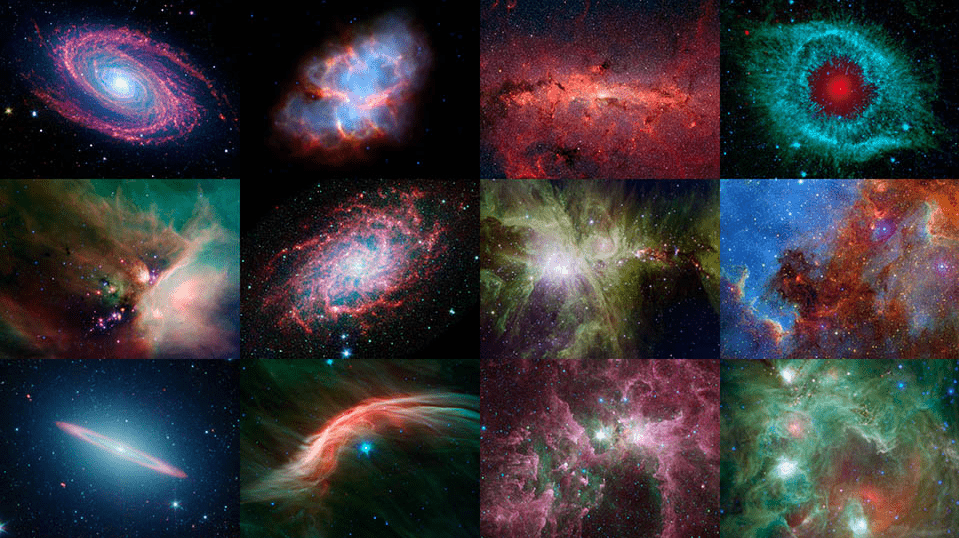

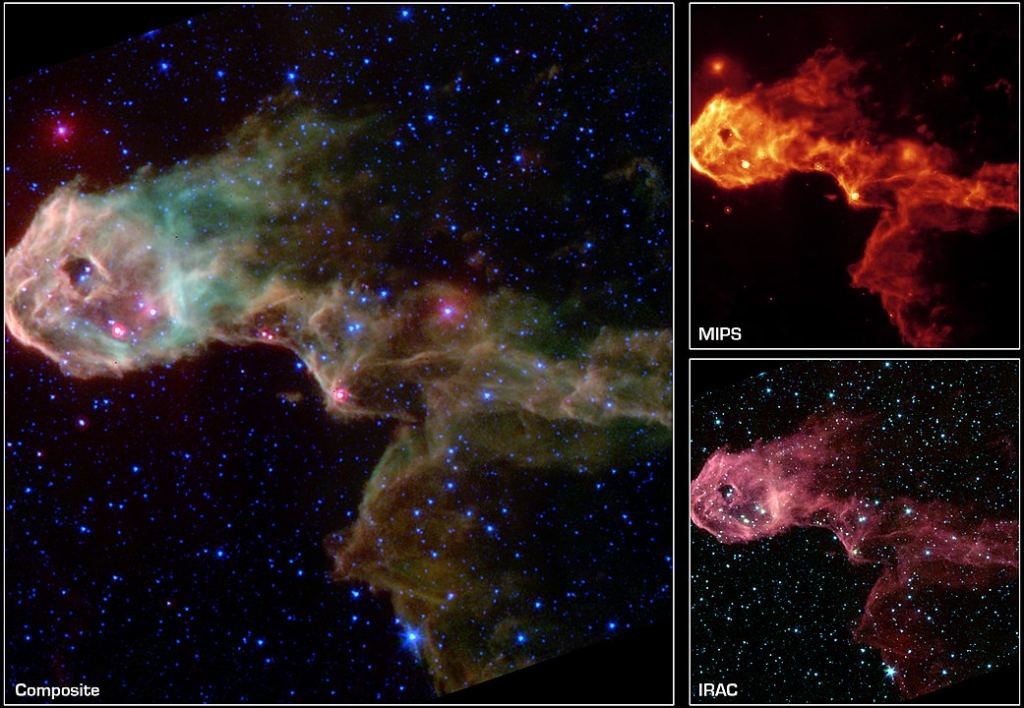

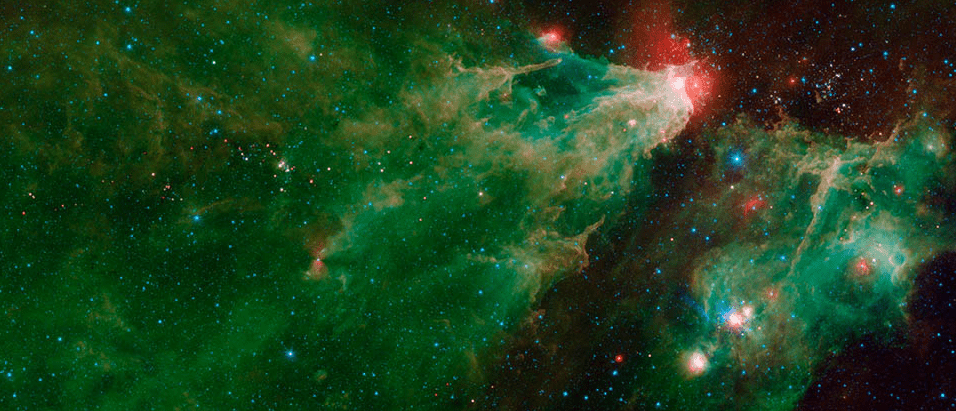

The first images that Spitzer captured were designed to show off the telescope's capabilities, and they're stunning.

"Spitzer has taught us about entirely new aspects of the cosmos and taken us many steps further in understanding how the universe works, addressing questions about our origins, and whether or not are we alone," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. "This Great Observatory has also identified some important and new questions and tantalizing objects for further study, mapping a path for future investigations to follow. Its immense impact on science certainly will last well beyond the end of its mission."

It's impossible to list all of the work done by Spitzer. But a number of things stand out.

Spitzer helped discover additional exoplanets around the TRAPPIST-1 system. After a team of Belgian astronomers discovered the first three planets in the system, follow up observations by Spitzer and other facilities identified four other exoplanets. Spitzer was also used to

The Spitzer Space Telescope was also the first telescope to study and characterize the atmospheres of exoplanets. Spitzer obtained the detailed data, called spectra, for two different gas exoplanets. Called HD 209458b and HD 189733b, these so-called "hot Jupiters" are made of gas, but orbit much closer to their suns. Astronomers working with Spitzer were surprises at these results.

"This is an amazing surprise," said Spitzer project scientist Dr. Michael Werner said at the time. "We had no idea when we designed Spitzer that it would make such a dramatic step in characterizing exoplanets."

Spitzer's infrared capabilities allowed it to study the evolution of galaxies. It also showed us that what we thought was a single galaxy is in fact two galaxies.

Hopefully, Spitzer's successor, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), will launch soon. Spitzer's mission was extended when the JWST's launch was postponed, but it couldn't be extended indefinitely. Unfortunately NASA's without an infrared space telescope for a while.

"We leave behind a powerful scientific and technological legacy." Spitzer Project Manager Joseph Hunt

The JWST will pick up where Spitzer left off, but of course it's much more powerful than the Spitzer. The Spitzer may have been the first to characterize an exoplanet's atmosphere, but the JWST will take that to the next level. One of the JWST's main purposes is to study the composition of exoplanet atmosphere's in detail, looking for the building blocks of life.

"Everyone who has worked on this mission should be extremely proud today," said Spitzer Project Manager Joseph Hunt. "There are literally hundreds of people who contributed directly to Spitzer's success, and thousands who used its scientific capabilities to explore the universe. We leave behind a powerful scientific and technological legacy."

NASA has a comprehensive gallery of Spitzer images at the Spitzer website. A quick tour of that website will make clear the space telescope's contribution to astronomy.

More:

- Press Release: N ASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope Ends Mission of Astronomical Discovery

- NASA/JPL: The Spitzer Space Telescope

- Universe Today: Top 10 Really Cool Infrared Images from Spitzer

Universe Today

Universe Today