Billions of years ago, Mars had liquid water on its surface in the form of lakes, streams, and even an ocean that covered much of its northern hemisphere. The evidence of this warmer, wetter past is written in many places across the landscape in the form of alluvial fans, deltas, and mineral-rich clay deposits. However, for over half a century, scientists have been debating whether or not liquid water exists on Mars today.

According to new research by Norbert Schorghofer – the Senior Scientist at the Planetary Science Institute – briny water may form intermittently on the surface of Mars. While very short-lived (just a few days a year), the potential presence of seasonal brines on the Martian surface would tell us much about the seasonal cycles of the Red Planet, as well as help to resolve one of its most enduring mysteries.

Schorghofer’s study, titled “Mars: Quantitative Evaluation of Crocus Melting behind Boulders“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal. To address the question of whether seasonal water frost can melt, thus producing liquid water, Schorghofer considered a suite of quantitative models, as well as updated info on heat convection and a three-dimensional surface energy balance model.

While much of the water that once existed on Mars’ has been preserved in the form of its polar ice caps, the presence of liquid water is very difficult to determine. The planet undergoes seasonal cycles like Earth, which would lead one to conclude that this ice periodically melts. However, the low-pressure environment and rapid temperature changes on Mars cause this ice to sublimate long before it reaches its melting point.

On Mars, atmospheric pressure ranges from 0.4 to 0.87 kilopascals (kPa), which is the equivalent of less than 1% of Earth’s at sea level. This places it close to the triple point pressure of H2O – the minimum pressure necessary for liquid water to exist. Meanwhile, the surface heats very quickly when exposed to sunshine, which results in massive changes in temperature throughout the day.

As Schorghofer explained in a recent PSI press release:

“Mars has plenty of cold ice-rich regions and plenty of warm ice-free regions, but icy regions where the temperature rises above the melting point are a sweet spot that is nearly impossible to find. That sweet spot is where liquid water would form.”

Schorghofer envisions these “sweet spots” as being located in the mid-latitudes around protruding topography (e.g. boulders and tall rock formations). During the winter, these regions would cast shadows continually, creating very cold temperature environments where water frost could accumulate.

When Spring comes, these same spots would become exposed to direct sunlight. This would cause the water frosts to be heated to close to the melting point of water after one or two Martian days (aka. sols). According to Schorghofer’s detailed model calculations, the temperature would change very rapidly, rising from -128 °C (-200 °F) in the morning to -10 °C (14 °F) by noon.

Wherever these water frost deposits formed on salt-rich ground, their melting point would be depressed to the point where it would melt at -10 °C. This means that not all of the frost would sublimate and become gaseous. Some of it would turn into brines that would endure until all of the ice has either melted or turned to vapor. This seasonal pattern would repeat again the following year.

Much like what happens in the southern polar region, carbon dioxide frosts could also build up during the winter in the shadowed areas behind protruding topography. The melting of water frosts would therefore only take place after the dry ice had vaporized – a point that scientists refer to as the “crocus date.” One or two sols after this date has passed, liquid water ice will begin to thaw to create water – known as “crocus melting.”

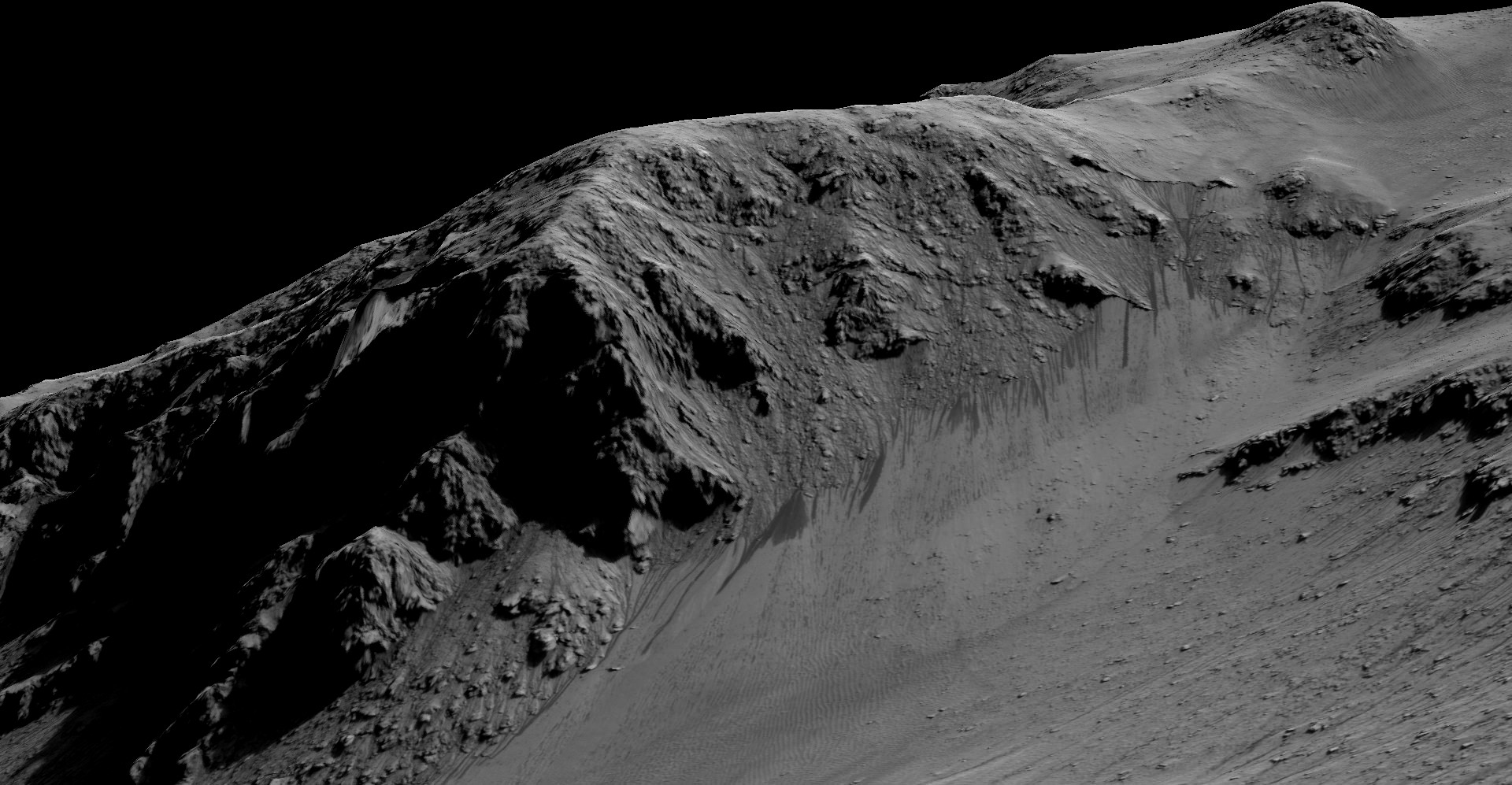

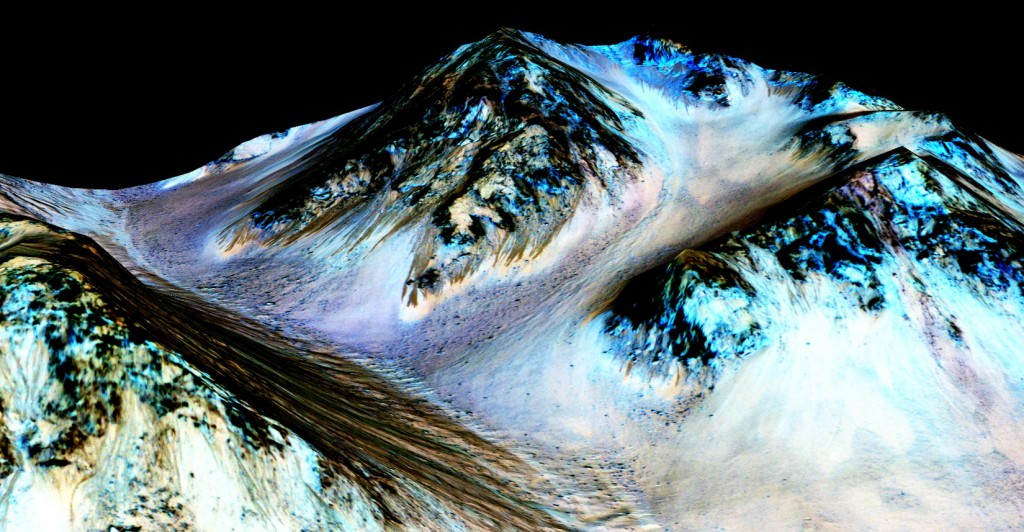

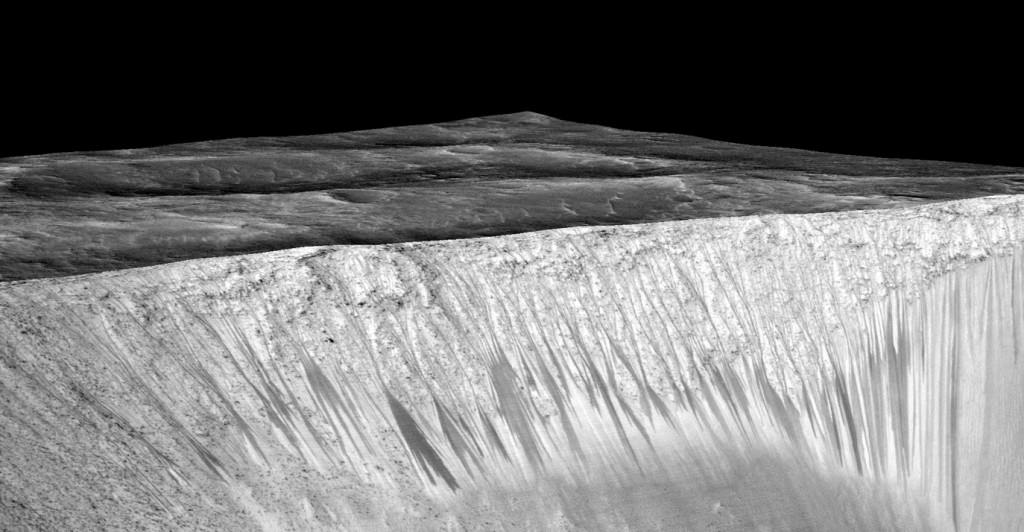

These findings build on previous experiments conducted by NASA that showed how chlorate-rich environments on Mars would be the most likely place to find water. Similar research has been conducted by numerous science teams that have questioned whether seasonal features around Mars’ equatorial regions – known as Recurring Slope Lineae (RSL) or “slope streaks” – are the result of brines forming.

So far, there is conflicting evidence as to what causes these features and whether they are the result of sand avalanches (“dry” mechanisms) or liquid water from groundwater springs, melting surface ice, or the formation of brines (“wet” mechanisms). As Schorghofer explained, his research and modeling are an additional indication that the “wet” school of thought is correct.

“Answering the question whether crocus melting of seasonal water ice actually occurs on Mars required a slew of detailed quantitative calculations – the numbers really matter. It took decades to develop the necessary quantitative models.”

This summer, NASA’s Mars 2020 rover will launch from Cape Canaveral to begin its six-month-long journey to Mars. Once there, it will join Curiosity and a host of other missions that are currently looking for evidence of Mars’ watery past. With any luck, some direct evidence that liquid water exists there today will also be found! Aside from settling a decades-long debate, it would be good news for all those hoping to go there in the future!

Further Reading: PSI, The Astrophysical Journal