Since December of 2017, NASA has been working towards the goal of sending "the next man and first woman" to the Moon by 2024, which will be the first crewed lunar mission since the Apollo Program. As part of this mission, known as Project Artemis, NASA has been developing both the Space Launch System (SLS) and the Orion spacecraft, which will allow the astronauts to make the journey.

Originally, it was hoped that the first uncrewed flight of the SLS and Orion (*Artemis I*) would take place later this year. But according to recent statements by Associate Administrator Steve Jurczyk, this inaugural launch will most likely take place "mid to late" in 2021. This is the latest in a series of delays for the high-profile project, which has been making impressive progress nevertheless.

The announcement was made on Saturday, Feb. 28th, during the kickoff meeting at the Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium (LSIC) at NASA's Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. As part of NASA's Lunar Surface Innovation Initiative, this consortium brings academic and industry experiments together with government officials to discuss and design the necessary technologies and systems that will enable lunar exploration.

In the course of the keynote address, Jurczyk shared how all the elements that will be needed for the first crewed mission (*Artemis 3*) in 2024 are currently in development or soon will be. This includes the Orion spacecraft - which is in its final phase of vacuum chamber testing at NASA's Plum Brook Station - and the SLS core stage, which is awaiting a static-fire test at Stennis Space Center (scheduled for later this year).

Once the tests are complete, the SLS core stage will be shipped to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida where crews will begin the process of integrating it with the Orion spacecraft and an upper stage booster. As for when the rocket and spacecraft will be ready to fly, Jurczyk indicated that it would not be in 2020 (as previously intended) but "hopefully in the mid '21 timeframe, mid to late '21 timeframe for Artemis 1."

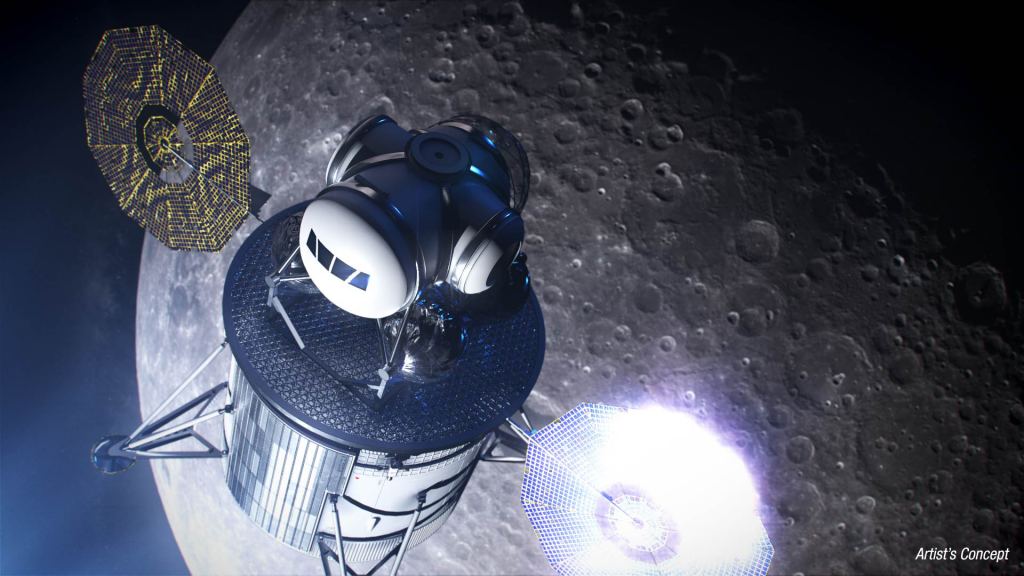

Jurczyk also claimed that the administration was making progress on other pieces of the mission architecture, like the development of modules and systems that will go into the creation of the Lunar Gateway. This includes awarding contracts to Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems (NGIS) and Maxaar Technologies to build the HAbitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO) and the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE), respectively.

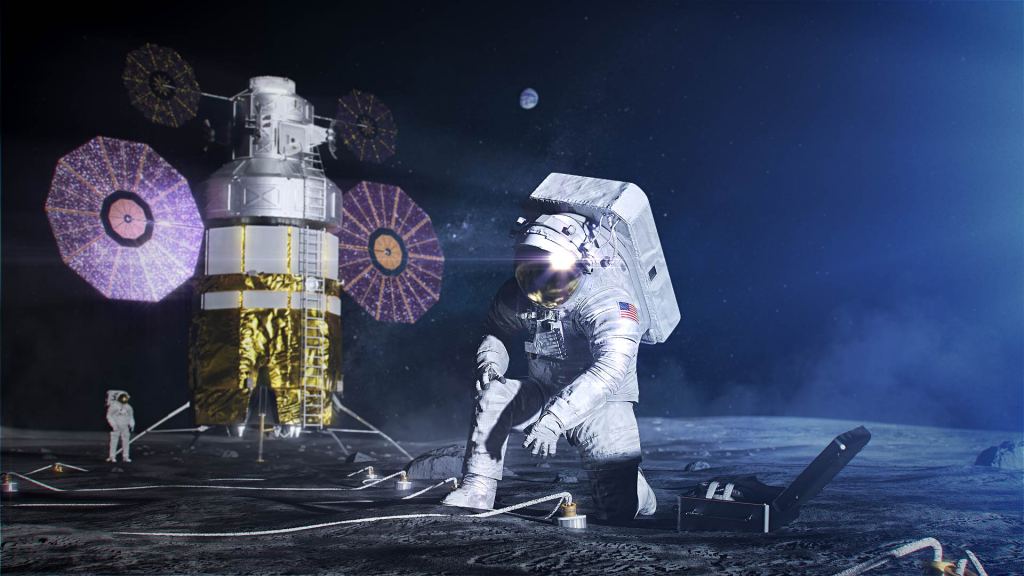

Then there's the Lunar Lander element, for which NASA issued an open call for concepts back in September of 2019. To date, NASA has awarded to Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, Blue Origin, and Draper Laboratory, and others to produce their own concepts (which include a reusable lander deployed from the Gateway or an expendable one deployed from the Orion spacecraft).

It's not clear if this latest delay will jeopardize Project Artemis' goal of landing a crew on the Moon by 2024. However, it is merely the latest in a program that has been plagued by delays from the beginning. At present, the SLS program is already years behind in its development goals and billions of dollars over budget.

What's more, NASA is also dealing with the problem of conflicting statements and inconsistency. On the one hand, they are contending with stringent deadlines and the possible cancellation of the Lunar Gateway - a key element in the " Moon to Mars " plan. On the other, there are the statements issued by President Trump during the past nine months that suggest that the focus of his administration could be shifting.

On June 7th, 2019, Trump tweeted "NASA should NOT be talking about going to the Moon - We did that 50 years ago. They should be focused on the much bigger things we are doing, including Mars..." This was followed by similar statements made back in September during the visit of Australian PM Scott Morrison, where he told reporters:

"We're going to Mars. We're stopping at the moon. The moon is actually a launching pad. That's why we're stopping at the moon. I said, 'Hey, we've done the moon. That's not so exciting.' So we'll be doing the moon. But we'll really be doing Mars."

This stands in contrast to Project Artemis' priorities, as set by VP Pence Administrator Jim Bridenstine (who was appointed by the Trump administration in 2017). Put simply, Artemis is all about getting to the Moon faster, even if it meant serious shake-ups at the agency. This much was demonstrated with the demotions of longtime heads William Gerstenmaier and William Hill in July of 2019.

In the wake of Pence's announcement in March of 2019, there have also been changes in terms of the design for mission architecture - for example, the Lunar Lander. Whereas this element was originally intended to be a reusable spacecraft that would ferry astronauts between the Lunar Gateway and the lunar surface, more recent designs are for an expendable vehicle that would travel take astronauts from the Orion spacecraft to the lunar surface and back again.

While not much is clear at this point, NASA continues to make progress towards their eventual goal, regardless of delays or cost overruns. Provided the budget environment holds and there is a continued commitment on behalf of political leaders, Artemis will happen. It may not happen by 2024; but then again, there were many at NASA who said that was never a realistic timeline to begin with.

Originally, the long-awaited return to the Moon was slated it to happen no sooner than 2028, giving the SLS and the Gateway plenty of time to be completed. This would not ensure that lunar missions would be sustainable and keep going after the next crewed missions to the surface, but that NASA would be well-positioned to set its sights on Mars next.

As usual, we'll all just have to wait and see what materializes. In the meantime, be sure to check out this footage of the opening remarks of the LSIC, courtesy of the John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL):

Further Reading: SpaceNews*, Parabolic Arc*

Universe Today

Universe Today