What do coal, crude oil, and truffles have in common? Go ahead. We'll wait.

The answer is thiophenes, a molecule that behaves a lot like benzene. Crude oil, coal, and truffles all contain thiophenes. So do a few other substances. MSL Curiosity found thiophenes on Mars, and though that doesn't conclusively prove that Mars once hosted life, its discovery is an important milestone for the rover. Especially since truffles are alive, and oil and coal used to be, sort of.

A quote from NASA's Curiosity website reminds us what the rover's mission is: "Curiosity was designed to assess whether Mars ever had an environment able to support small life forms called microbes. In other words, its mission is to determine the planet's 'habitability.' "

A pair of scientists from Berlin's Technical University thinks that the thiophenes Curiosity found on Mars could be a signature from early Martian life. If they're right, then Mars was, at one time, inhabited by simple life forms. They've presented their findings in a new paper.

The pair are Dirk Schulze-Makuch and Jacob Heinz. Schulze-Makuch is also an astrobiologist at Washington State University. Their paper is titled "Thiophenes on Mars: Biotic or Abiotic Origin?" It's published in the journal Astrobiology.

MSL Curiosity found the thiophenes in Martian sediments. It's one of a number of interesting molecules found on Mars that might have a biotic origin. Thiophenes can also have an abiotic origin through diagenesis, which are physical and chemical changes that take place as sediments become sedimentary rock.

In order to find the thiophenes in the Martian sediments, Curiosity had to first heat the sample above 500 Celsius. Then Curiosity examined it with the SAM (Sample Analysis at Mars) instrument. SAM analyzed the gases coming off the sample using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. SAM is actually three instruments in one, and together they search for organic chemicals.

"We identified several biological pathways for thiophenes that seem more likely than chemical ones, but we still need proof," Dirk Schulze-Makuch said in a press release. "If you find thiophenes on Earth, then you would think they are biological, but on Mars, of course, the bar to prove that has to be quite a bit higher."

Thiophenes have a structure that suggests a possible biotic origin. They have four carbon atoms and a single sulfur atom arranged in a ring, with hydrogen atoms. Hydrocarbons are essential elements in organic chemistry, and hydrocarbon molecules containing atoms of sulfur are an important part of the study of organic chemistry.

There are non-biological sources of thiophenes. They can be created by meteor impacts, and by a process called thermochemical sulfate reduction, where compounds are heated above 120 Celsius (248 F).

But it's the biological sources of thiophenes that are the most interesting. In the distant past, perhaps about 3 billion years ago, Mars was a much different place. It likely had a warm and wet environment that could've harbored life. Those ancient bacteria could've facilitated a sulfate reduction process biologically, which resulted in the thiophenes that Curiosity detected.

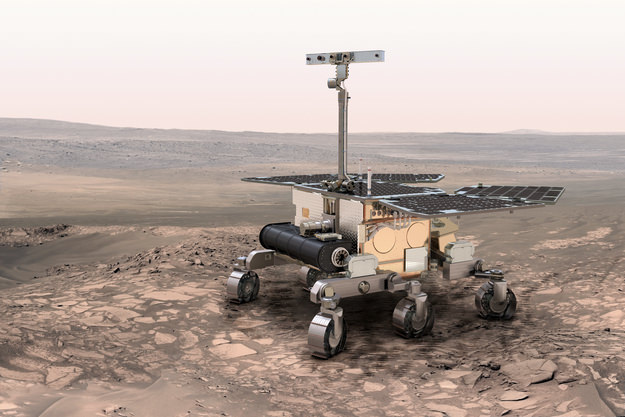

Technology moves quickly. Curiosity was much more advanced than its predecessors Spirit and Opportunity. It uses technology that breaks large molecules down into smaller molecules for analysis. But when the next Mars rover, the ESA's ExoMars mission, arrives on the red planet, it'll bring even more advanced technology.

ExoMars' MOMA (Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer) is the premier astrobiology instrument on the ExoMars rover, and also the largest instrument. It's a little more refined than Curiosity's instrument, and it doesn't rely on fragmentation to study molecules. MOMA will allow the collection and study of larger molecules.

MOMA will use the concept of homochirality to identify molecules as either biotic or abiotic, something that MSL Curiosity can't do. Homochirality is a property of amino acids and sugars. Many of the organic molecules necessary for life, including amino acids and sugars, can come in both left-handed and right-handed types, referred to as their chirality.

In Earth life, 19 of the 20 amino acids are homochiral and left-handed, while sugars, which are part of RNA and DNA, are homochiral and right-handed. Homochirality is essential for an efficient metabolism. But the same chemicals produced in a laboratory will have equal abundances of left-handed and right-handed types. The basic idea is that if we find homochiral building blocks of life, they likely have a biological source.

Isotope ratios can also differentiate between the same atoms with either biotic or abiotic origins. Schulze-Makuch and Heinze, the authors of this paper, think that some of the data from the ExoMars rover should be used to also look for isotopes of carbon and sulfur. In particular, the lighter isotopes of both. They think that's where we're most likely to find a biological origin.

"Organisms are 'lazy.' They would rather use the light isotope variations of the element because it costs them less energy," Schulze-Makuch said.

Lifeforms tend to alter the balance between light isotopes and heavy isotopes of the elements they produce. That ratio is different than the ratio in the same elements in their building blocks. That's a "tell-tale sign of life" according to Schulze Makuch.

The discussion over life on Mars has been ongoing for decades. When the Viking landers were on Mars in 1976, they conducted the very first in-situ measurements, looking for organic compounds. What they found is still somewhat controversial today, because no lab experiments have been able to completely recreate those results. However, it's widely believed in the scientific community that the Viking findings can be explained by abiotic sources.

The ExoMars rover is our next step in understanding ancient Mars' habitability. Its experimental results may bring us one step closer to knowing definitively if Mars once hosted life. But it might not get us all the way to that conclusion, unfortunately.

"As Carl Sagan said 'extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,'" Schulze-Makuch said. "I think the proof will really require that we actually send people there, and an astronaut looks through a microscope and sees a moving microbe."

Universe Today

Universe Today