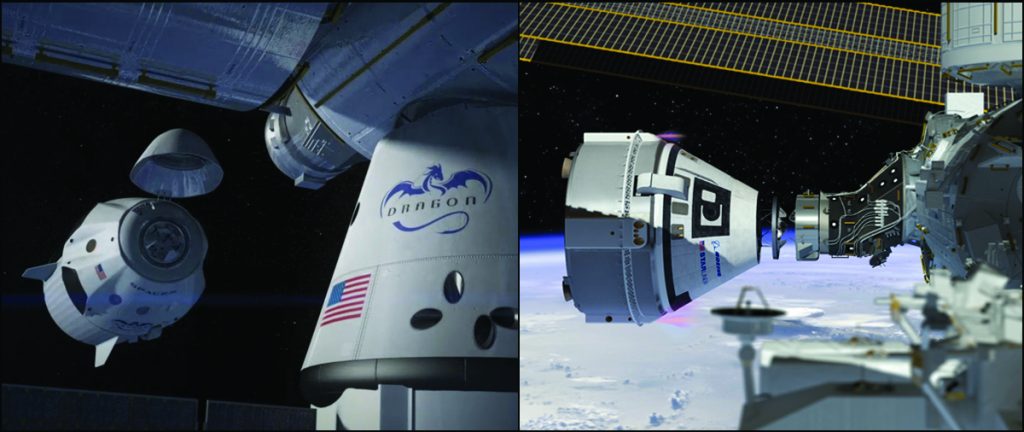

With the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011, NASA has become dependent on its Russian counterparts to send and return astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS). Hoping to restore domestic launch capability to American soil, NASA has contracted with aerospace developers like SpaceX and Boeing to develop crew-capable spacecraft, as part of their Commercial Crew Program (CCP).

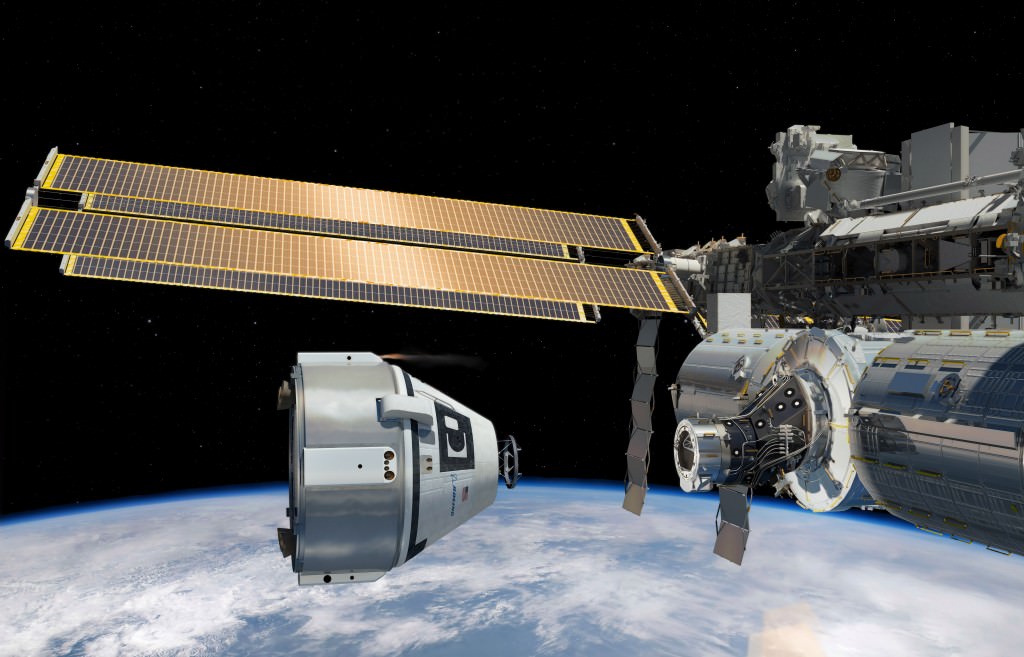

After years of development, Boeing managed to get their CST-100 Starliner ready for its first uncrewed test flight on December 20th, 2019. Unfortunately, a hiccup occurred during the mission that prevented the spacecraft docking with the ISS. After an independent review of the mission, NASA and Boeing have determined that 61 corrective actions need to be taken before the Starliner can fly again.

The Calypso, it should be noted, was successfully launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and made it safely home (touching down near White Sands, New Mexico) – thus proving that the design is space-worthy. However, the spacecraft experienced an “elapsed timing error” during the flight that caused its thrusters to experience an intense period of thruster activity that burned through much of the spacecraft’s fuel.

Because of this premature burn, mission controllers decided to scrub the spacecraft’s planned rendezvous with the ISS and bring the Calypso home. After looking over the mission data, three major anomalies were found that are believed to have contributed to the error. These included two software coding errors as well as an unexpected loss of space-to-ground communications.

Shortly thereafter, a joint NASA-Boeing Independent Review Team was formed to investigate these three anomalies. In the course of their investigation, the team identified several issues – technical and organizational – related to Boeing’s work. Concurrently, NASA conducted a review of its involvement in the flight test and identified several areas where they could make improvements with regard to their participation.

The first anomaly, designated “Mission Elapsed Timer (MET)”, occurred following spacecraft separation with the Altas V launch vehicle. At this time, the Starliner was programmed to execute a few maneuvers tied to the mission timer. Due to an error in the coding, the Starliner synced its clock with the rocket, which led to the spacecraft thinking it was at a different point in the mission following separation.

The second anomaly, the “Service Module Disposal Burn”, occurred during the Starliner’s crew and service module separation sequence. This software error is what led the Starliner to fire its corrective thrusters at the wrong time and to consume too much of the spacecraft’s fuel. Last, but not least, there was the “Space-to-Ground Communications (S/G)” anomaly which prevented the flight control team from taking corrective action in time.

As the review determined, there was an “intermittent S/G forward link” issue that impeded the flight control team’s ability to control Starliner during the mission. These issues were all identified as posing a significant risk for future, crewed missions. Altogether, the review team identified 61 corrective and preventative actions to address the two software anomalies, which were organized into four categories.

According to a statement posted on NASA Blogs, they include:

- Perform code modifications: Boeing will review and correct the coding for the mission elapsed timer and service module disposal burn.

- Improve focused systems engineering: Boeing will strengthen its review process including better peer and control board reviews, and improve its software process training.

- Improve software testing: Boeing will increase the fidelity in the testing of its software during all phases of flight. This includes improved end-to-end testing with the simulations, or emulators, similar enough to the actual flight system to adequately uncover issues.

- Ensure product integrity: Boeing will check its software coding as hardware design changes are implemented into its system design.

The review team is still investigating the intermittent space-to-ground communications anomaly and will issue a final report by the end of March. However, they have identified the root cause and recommended specific hardware improvements in the meantime. Apparently, the issue was a result of radio-frequency interference that occurred as the spacecraft briefly passed between two other satellites.

In addition to the software issues raised, the review team also identified organizational issues that contributed to the anomalies. In response, Boeing announced that it plans to improve its testing, review, and approval processes for hardware and software and institute changes with its engineering board authority.

Boeing accepted the full action list and has already begun work on implementing several of the specified actions. The company is also working to refine its implementation schedule and incorporate the full list of actions into its plans. The joint review team has been tasked by NASA and Boeing to track the progress and execution of each action going forward.

In the meantime, NASA has also come up with a comprehensive plan to improve its software verification and validation process, as well as improving the overall system integration of the Starliner. The agency also plans to be more active when it comes to hazard reports, test environments, and audits and will increase its support and co-locate personnel to the Boeing software team.

While NASA and Boeing have taken significant steps to address any technical and organizational problems that are believed to have contributed to last December’s partial failure, more work needs to happen before another uncrewed test flight can be scheduled. NASA also plans to perform an Organization Safety Assessment (OSA) of the workplace culture at Boeing prior to any future test flights.

In accordance with the NASA Procedural Requirements, NASA has designated the test flight of the Starliner as a “high visibility close call.” In short, nobody was hurt and NASA has determined that if the Starliner had crew aboard, there would have been no injuries. However, the anomalies are too big to ignore and could have led to serious consequences under different circumstances.

Since 2004, when NASA updated its procedural requirement, the agency has designated 24 flights and tests as high visibility close calls. It just goes to reinforce that when it comes to space exploration, safety is paramount. This means that rigorous testing has to be done to ensure that all issues – foreseen and unforeseen alike – can be worked out long before we start sending humans to space.

However, between Boeing’s progress and the success of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon module, it is all but certain that domestic launch capability will be restored to US soil soon.

Further Reading: NASA