In 2010, President Barack Obama signed the NASA Authorization Act, which charged NASA with developing all the necessary technologies and components to allow for a crewed mission to Mars. Key to this was the development of the Space Launch System (SLS), the Orion spacecraft, and an orbiting lunar habitat (aka. the Lunar Gateway).

However, in recent years, these plans have been altered considerably to prioritize “returning to the Moon.” Formally named Project Artemis, VP Pence emphasized in March of 2019 that NASA must return to the Moon by 2024, even if it meant some shakeups were needed. In the latest news, NASA has indicated that the Lunar Gateway is no longer a priority, as part of a plan to “de-risk” the mandatory tasks associated with Artemis.

These sentiments were expressed by Doug Loverro, who replaced William Gerstenmaier in July of 2019 as part of a shakeup designed to expedite progress with the SLS and the Artemis program in general. As Loverro explained during a NASA Advisory Council science committee (held on Friday, March 13th), he has been working to “de-risk” Artemis so NASA can focus on meeting the mandatory goals of Artemis and its 2024 deadline.

As Lovarro explained, this means focusing on technologies and activities that NASA already has experience developing. He also stated that those risks that can’t be eliminated need to be “burned down”. All of this is essential, he claimed, to creating the necessary mission architecture to land astronauts on the Moon by 2024. As he summarized:

“What are we going to do to go ahead and make that happen? And the answer is you’ve got to go ahead and remove all the things that add to program risk along the way.

“What are all of the risks that can get in our way in a four-and-a-half-year schedule and how do we go ahead and pull them all early into program, or eliminate them from the program altogether by going ahead and making wise technical or programmatic choices?”

For this reason, he said during the latter half of the session, the Lunar Gateway had to be removed as a critical element to the program. This comes on the heels of what Associate Administrator Steve Jurczyk announced back in February at the LSIC’s kickoff meeting. It was here that Jurczyk explained that the first mission (Artemis 1) would likely be delayed and would take place in “mid to late” 2021.

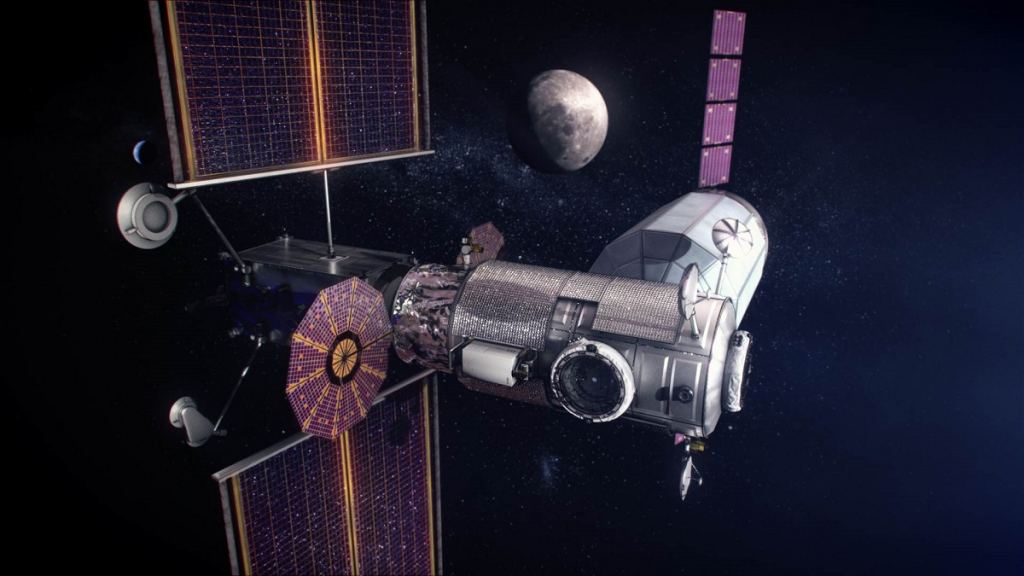

Another reason cited by Lovarro for the decision was the likelihood that the Gateway will fall behind in its development schedule. This he attributed to the fact that the first module, the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE), calls for an advanced solar-electric propulsion system that will allow it to act as a sort of “space tug” for visiting spacecraft while also serving as the command and communications center of the Gateway.

In May of 2019, NASA announced that it had awarded a $375 million contract to Colorado-based aerospace company Maxar Technologies (formerly SSL) to develop the PPE. The design called for a 50-kilowatt solar electric propulsion (SEP) spacecraft that will serve as a mobile command and service module and communications relay for human and robotic expeditions to the lunar surface.

Originally, NASA hoped to have this module ready by 2022 so that it could be launched as part of the Artemis 2 mission. The creation of other elements – like the HAbitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO), the ESPRIT service module, and the International Habitation Module (iHAB) – were also recently contracted to Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems (NGIS) and Airbus and OHB, respectively.

But as we reported in a previous article, since March of 2019, there have been concerns at NASA that the expedited timeline could come at the cost of sacrificing the Lunar Gateway. As an inside source reported at the time, there had been apparent pushback from the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) over continued funding for an element they considered unnecessary.

Of course, Loverro emphasized that NASA was not abandoning the Lunar Gateway and that removing it from the “critical path” would lead to a better Gateway program. For one, it will give NASA contractors more time to develop their modules, which were originally scheduled for completion beginning in 2026. Second, it will cut the associated costs for Project Artemis. As he said:

“We can now tell them 100% positively it will be there because we’ve changed that program to a much more what I would call solid, accomplishable schedule… Frankly, had we not done that simplification, I was going to have to cancel Gateway because I couldn’t afford it. By simplifying it and taking it out of the critical path, I can now keep it on track.”

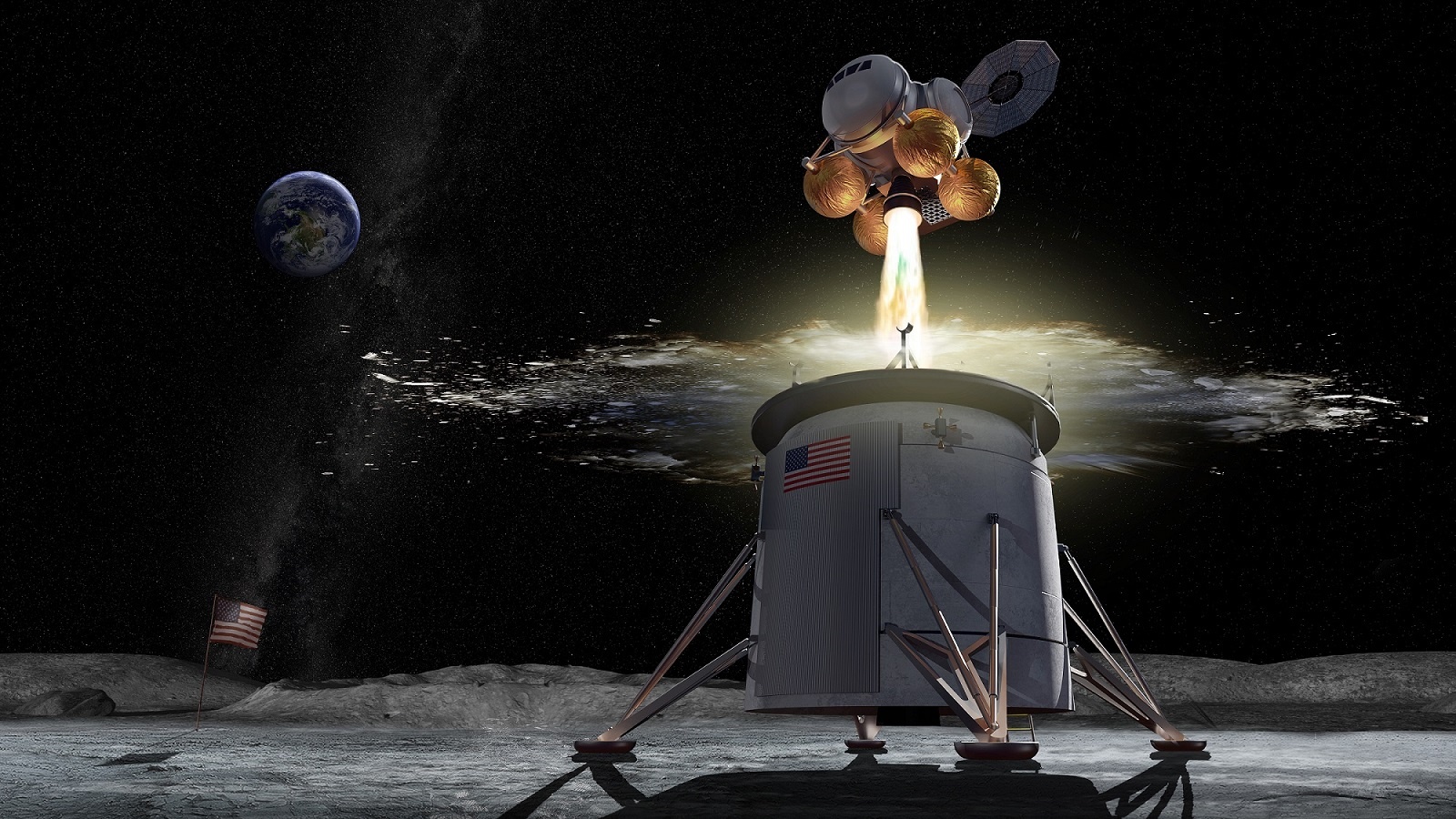

This means that the Artemis missions will no longer rely on the Gateway and will instead use a lunar lander incorporated into the Orion spacecraft. Here too, Loverro hinted that there would be changes in order to cut costs and reduce risks. Previously, NASA had proposed a reusable three-stage lander consisting of an ascent module, descent module, and transfer module – all of which would be assembled at the Gateway.

Instead, Loverro proposed taking the time-tested and proven approach. This likely means that the Artemis lander will be a two-stage spacecraft, like the lunar module that took the Apollo astronauts to the Moon, consisting of a descent stage and an ascent stage. In Sept. of 2019, when NASA announced the decision to fast-track the development of the lunar lander, contractors were given the option of suggesting non-reusable alternatives as well.

“Program risk is driven by which things haven’t you done in space before that you would now have to do in this mission,” said Loverro. “We’ve never done that before, so we’d like to try to avoid doing things we’ve never done before.” In the meantime, the finalized plan for Artemis is expected in the near future, though Loverro could not provide a more concrete idea of when it would be unveiled.

In effect, this means that Artemis will be a “boots and flags” operation like the Apollo missions, something that NASA was originally hoping to avoid. On top of that, there have been severely mixed messages coming from this administration. Whereas VP Pence has remained resolute in his stated commitment to Artemis, President Trump has publicly criticized the project for retreading on old ground.

“NASA should NOT be talking about going to the Moon – We did that 50 years ago. They should be focused on the much bigger things we are doing, including Mars…” he tweeted on June 7th, 2019. This was followed by similar statements made in September during the visit of Australian PM Scott Morrison, where he stated to press that were in attendance:

“We’re going to Mars. We’re stopping at the moon. The moon is actually a launching pad. That’s why we’re stopping at the moon. I said, ‘Hey, we’ve done the moon. That’s not so exciting.’ So we’ll be doing the moon. But we’ll really be doing Mars.”

Still, all signs point toward NASA still being committed to establishing a “sustainable lunar exploration” program on the Moon, which is intended to include the creation of a permanent lunar outpost. Examples of this include the ESA’s proposed International Moon Village and China’s plan for building an outpost in the South Pole-Aitken Basin.

Nevertheless, the decision to make a lunar landing happen by 2024 “by any means necessary” (not to mention conflicting statements from the White House) has caused its fair share of confusion and chaos around NASA. With the “Moon to Mars” framework, the creation of the Lunar Gateway and a crewed mission to the lunar surface by 2028 were interdependent.

But if there’s one thing that space exploration has taught us, it is that budgets and priorities change regularly, which is why it is important to be flexible and adapt. One way or another, we’re going back to the Moon and we intend to stay there! The means to do so may just take a little longer than expected.

Further Reading: Space News

While I know Universe Today’s recent MO has been to criticize the current Presidential administration, this “controlled stall” of returning humans to the Moon and then venturing onto Mars has spanned multiple Presidential administrations on both sides.

Being an amateur spaceflight historian myself, I can say that NASA’s approach to returning to the Moon now, vs. the all-hands-on-board approach of NASA from the late 50’s through the early 70’s could not be more different. We have now slowly but deliberately pushed this timeline back 20+ years from the original goal.

I often wonder whether the Secret Space Program is already a reality, and part of the reason for this stall is because we are already there. This is an idea that is quietly gaining traction, due to the US’s continued inability to set a concrete timeline, goal for exploration, and simply how we are going to get to the Moon and back in the first place.