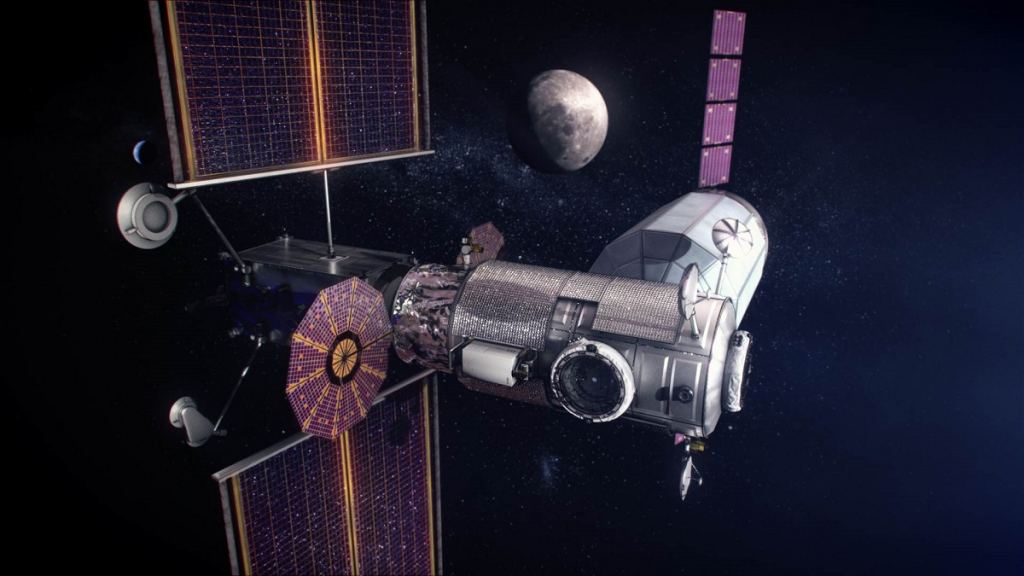

In the coming years, NASA plans to return astronauts to the Moon as part of Project Artemis. However, the long-term goal is to establish a sustainable program for lunar exploration, as well as a permanent human presence on the Moon. A key aspect of this plan is the Lunar Gateway, an orbiting habitat that will allow for long-duration missions to the lunar surface (and eventually to Mars.)

To realize this goal, NASA is moving ahead with the development of the Space Launch System (SLS) and Orion spacecraft. The agency also recently announced that it has awarded its first contract to SpaceX as part of the Gateway Logistics Services (GLS) program. As per this agreement, SpaceX will be tasked with delivering cargo, experiments, and other supplies to the agency’s Lunar Gateway once it is deployed in orbit of the Moon.

For years, SpaceX has been providing launch services for NASA as part of their Commerical Resupply Services (CRS) to the International Space Station (ISS). In 2016, SpaceX and Boeing were contracted with NASA’s Commercial Crew Vehicle (CCV) program to restore domestic launch capability to US soil by developing vehicles that could transport astronauts to and from the ISS.

For this latest contract, SpaceX will similarly be delivering critical pressurized and unpressurized cargo, science experiments and supplies to the Gateway. This will include materials that are critical for expeditions to the lunar surface, samples obtained by astronauts for return to Earth, and supplies that will facilitate the Artemis missions. As NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine explained in a recent NASA press release:

“This contract award is another critical piece of our plan to return to the Moon sustainably. The Gateway is the cornerstone of the long-term Artemis architecture and this deep space commercial cargo capability integrates yet another American industry partner into our plans for human exploration at the Moon in preparation for a future mission to Mars.”

The GLS program is an indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity agreement to provide logistic services to the Gateway. It guarantees two missions per launch provider and establishes a fixed-price for services rendered. In total, the program will award a maximum of $7 billion for all commercial contracts and any additional missions that are deemed necessary.

“This is an exciting new chapter for human exploration,” added Mark Wiese, the Deep Space Logistics manager at the NASA Kennedy Space Center. “We are bringing the innovative thinking of commercial industry into our supply chain and helping ensure we’re able to support crews preparing for lunar surface expeditions by delivering the supplies they need ahead of time.”

Whereas cargo spacecraft providing logistic support stay docked with the ISS for six months on average, supply missions to the Gateway are expected to last from six to twelve months at a time. NASA estimates that Project Artemis will require one standard logistics service mission for each Artemis SLS/Orion crewed mission to the Gateway.

Last, but not least, the GLS contract enables NASA to order missions for as long as 12 years with a 15-year performance period and allows for new providers to compete for added contracts. As President and Chief Operating Officer Gwynne Shotwell expressed, SpaceX is happy to be part of NASA’s renewed efforts to explore the Moon:

“Returning to the Moon and supporting future space exploration requires affordable delivery of significant amounts of cargo. Through our partnership with NASA, SpaceX has been delivering scientific research and critical supplies to the International Space Station since 2012, and we are honored to continue the work beyond Earth’s orbit and carry Artemis cargo to Gateway.”

Back in March, Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations Doug Loverro (who replaced William Gerstenmaier in July of 2019) indicated that the Gateway is no longer necessary for Project Artemis. This decision was part of Loverro’s desire to “de-risk” Project Artemis and ensure that the agency can meet their deadline of returning to the Moon by 2024.

Nevertheless, the Gateway is still vital to NASA’s plans for a sustainable lunar exploration program, which includes working with international and commercial partners to develop a permanent outpost around the southern polar region. It is also essential for NASA’s eventual plans for a crewed mission to Mars, which may or may not happen by the 2030s at this point.

According to Dan Hartman, Gateway program manager at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, the program to build this orbital habitat is still on:

“We’re making significant progress moving from our concept of the Gateway to reality. Bringing a logistics provider onboard ensures we can transport all the critical supplies we need for the Gateway and on the lunar surface to do research and technology demonstrations in space that we can’t do anywhere else. We also anticipate performing a variety of research on and within the logistics module.”

It’s therefore unclear at this point whether or not these supply services will be mounted as part of the first three Artemis missions (which will involve the first crewed to the Moon since 1972) or during the remainder of the program, which is scheduled to run until 2030. But once up and running, we can expect companies like SpaceX will be executing lucrative contracts to keep it running.

Further Reading: NASA

In tweets Musk anticipates that Starship, if all goes well, will then have such a heritage that it can replace specifically (IIRC) Dragon XL. And discuss landing on the Moon, which will necessitate a hover slam *above* ground (i.e. falling the rest of the way) due to high thrust to weight ratio even at max throttle.