The universe is filled with matter, and we don’t know why. We know how matter was created, and can even create matter in the lab, but there’s a catch. Every time we create matter in particle accelerators, we get an equal amount of antimatter. This is perfectly fine for the lab, but if the big bang created equal amounts of matter and antimatter, the two would have destroyed each other early on, leaving a cosmic sea of photons and no matter. If you are reading this, that clearly didn’t happen.

It remains one of the greatest mysteries in cosmology, and it all comes down to symmetry in physics. Much of physics is rooted in the principles of conservation and symmetry. Space seems to be the same in all directions, and so momentum is conserved. This means if you throw a ball in empty space, it will continue its motion indefinitely. Time symmetry means that mass-energy is conserved, and so on. The connection between symmetry and conservation was first discovered by Emmy Noether and is now known as Noether’s theorem.

Since symmetry is foundational to physics, a great deal of research has looked at how and when symmetry can be broken. This is particularly true in particle physics. Since particles were first created in the early period of the universe, this also helps us understand how the universe came to be. In cosmology, one of the big ones is CP symmetry.

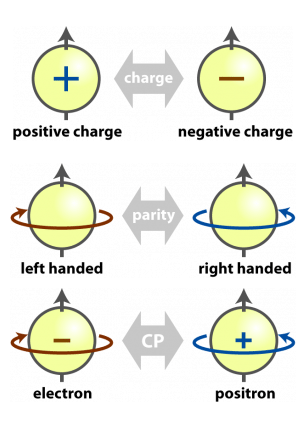

CP stands for charge-parity, and it represents a combination of two symmetries. Charge symmetry means that a universe made entirely of matter and one made of antimatter should behave in the same way. That is, they should be symmetrical. Parity can be described as a mirror image. If you hold up your right hand while looking in a mirror, your image will hold up its left hand. Parity symmetry means that if left and right were flipped in the universe, nothing should change.

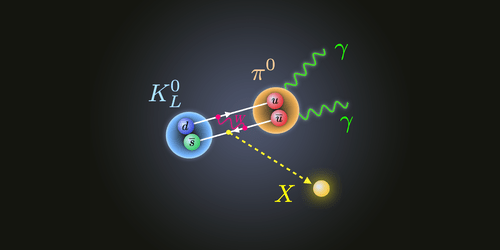

If CP symmetry always held, then our matter universe couldn’t exist. But we know that CP symmetry is sometimes violated. For example, in 1964 it was found that a neutral particle known as a Kaon came in two types that were CP duals of each other. If CP symmetry were conserved, then these two types of Kaons should decay at the same rate. What we found was that the two Kaon types decay at slightly different rates. The difference between the two is only about 3 parts in 1000, but it isn’t zero.

There are other known examples as well, but the problem is that even if you combine them all it isn’t enough to account for a matter-only universe. At the very least there must be another way to violate CP symmetry. Based on new research published in Nature, the answer could be neutrinos.

Neutrinos don’t have an electric charge, but they do appear in both matter and antimatter forms, so CP symmetry still applies to them. The problem is that they are notoriously difficult to detect. Even when you can’t detect them, it is difficult to distinguish neutrinos from antineutrinos.

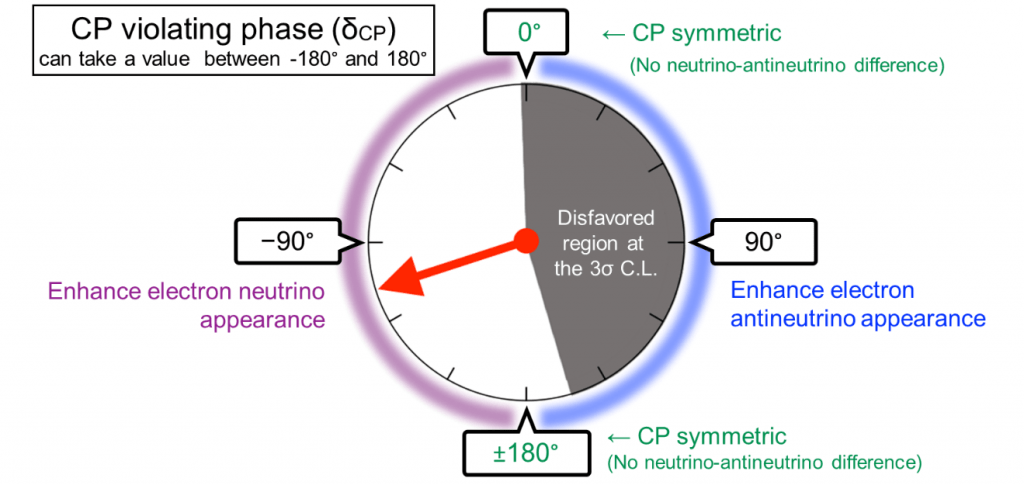

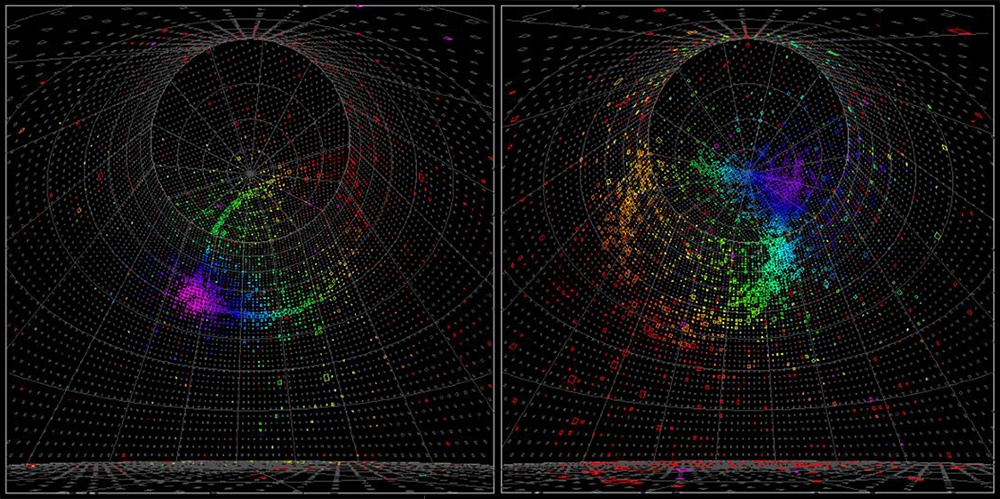

In this recent work, the T2K collaboration fired beams of neutrinos into a detector. T2K stands for T?kai to Kamioka, since the particle accelerator is located in the Japanese village of T?kai, and the neutrino detector is in Kamioka. Since the team controlled the neutrino beam, they could tell whether they were detecting neutrinos or antineutrinos. Collecting data over a decade, they found a CP violation in an effect known as neutrino oscillation.

Neutrinos have strange properties, and one of the strangest is oscillation. It turns out that neutrinos come in three types or flavors, and a neutrino can oscillate back and forth between each type. According to CP symmetry, both neutrinos and antineutrinos should oscillate at the same rate. But the T2K team found that they oscillate at different rates. Their rates are so different that they are almost maximally asymmetric. As a result, you are more likely to see matter neutrinos than antimatter ones.

This could be the matter universe answer we’ve been looking for, but we should be cautious. So far the evidence for neutrino asymmetry is weak. Even the authors admit their results aren’t strong enough to be conclusive. But they are very interesting. We’re going to need much more data to verify the result, but it is an important step toward understanding how we got here in the first place.

Reference: Kitahara, Teppei, et al. “New Physics Implications of Recent Search for K L? ?0 ? ?¯ at KOTO.”

Reference: T2K Collaboration. “Constraint on the Matter-Antimatter Symmetry-Violating Phase in Neutrino Oscillations.”

It’s interesting to try to catch up on the physics here. The standard model simplifies somewhat to three sectors of forces and quark and lepton matter, with the minimal remaining 1 Higgs and 3 generations of matter that is needed to get net matter.

Quarks are almost not in the game, but the charge free leptons – neutrinos – do the deed by way of maximal CP violation (i.e. ~ 95 % of max in this first tangible result). And again we may see minimality here, since long range electric charge would make charged matter start out with equal amount matter and antimatter.* The three so called Sakharov conditions are almost all implying various non-equilibrium physics at play, one explicitly so, so it is easy to think the essential CP breaking happened among leptons and then transferred to quarks in such physics. (Which transfer mechanism seems to be called sphalerons.)

But if this pans out, it may be another result of generic (multiverse) inflation. There is no Higgs mechanism within the standard model of particles that gives neutrinos the masses that ends up as CP violation. Like the vacuum (dark) energy the result seems to be an apparent and minimal finetuning for atoms of a habitable universe, while the large number of universes then are inhabitable.

* I’m not saying neutrinos or quarks existed before the Higgs/electroweak sector did, they all range below a low energy. There are many other problems with sphalerons et cetera, I take it, but they seem to be part of the physics of leptogenesis. I’m just noting that neutrinos seem far less constrained than the rest of baryon matter.