In the summer of 2019, a team of astronomers from NASA, the ESA, and the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON) announced the detection of the comet 2I/Borisov. This comet was the only second interstellar visitor observed passed through our Solar System, coming on the heels of the mysterious ‘Oumuamua. For this reason, astronomers from all over the world watched this comet intently as it made its closest pass to the Sun.

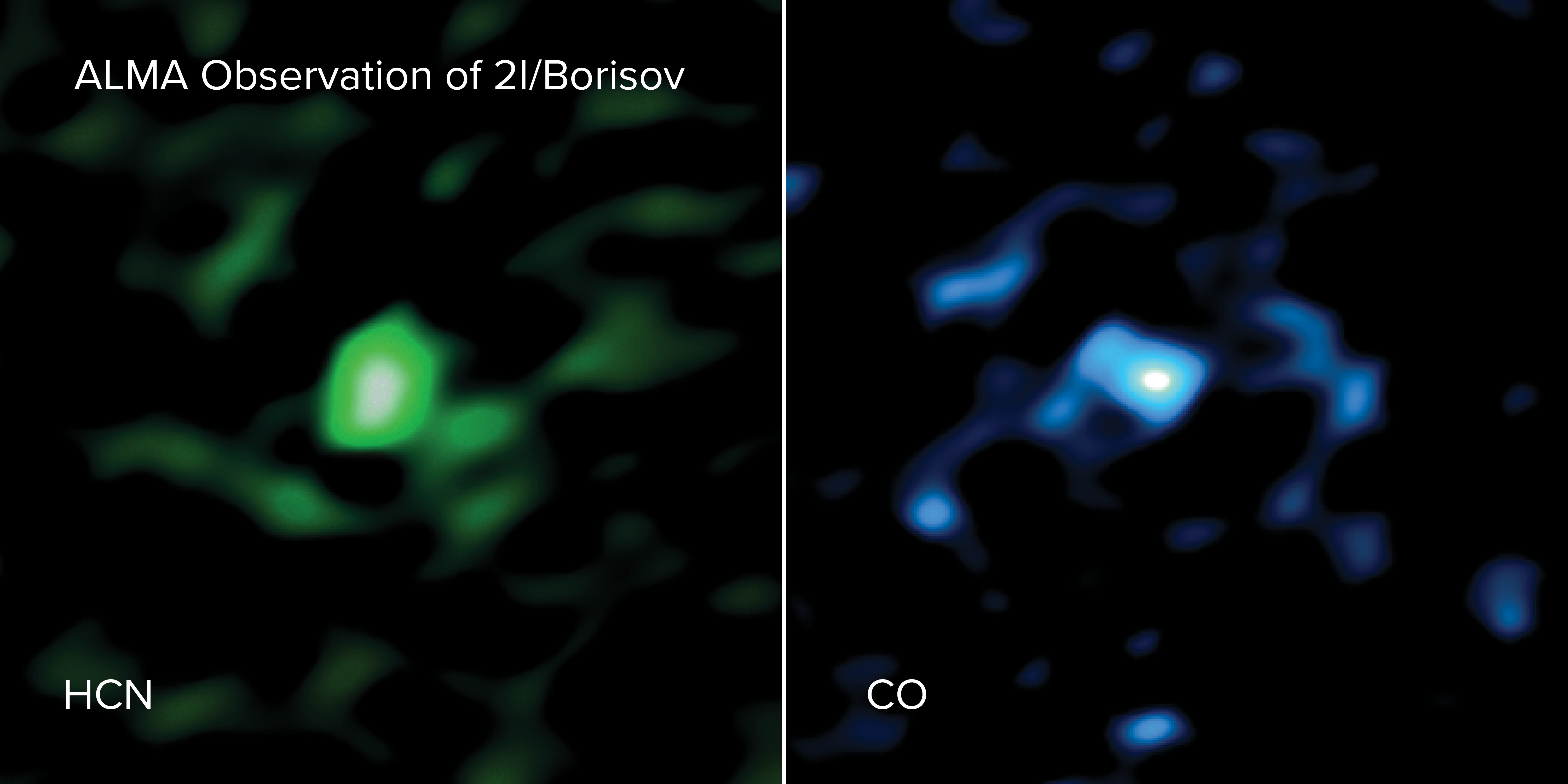

One such group, led by Martin Cordiner and Stefanie Milam of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, observed 2I/Borisov using the ESO’s Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in the Chilean Andes. This allowed them to observe the gases 2I/Borisov released as it moved closer to our Sun, thus providing the first-ever chemical composition readings of an interstellar object.

Astronomers are naturally interested in the study of comets because they are essentially material left over from the formation of the Solar System. In addition, they spend most of their lives at large distances from any star and in very cold environments. The majority of comets observed in the Solar System, for example, originated in the Kuiper Belt or the Oort Cloud, depending on whether they are short-period or long-period comets.

In addition, the interior composition of comets has not changed significantly since the formation of the Solar System. Therefore, the study of their interiors can tell scientists a great deal about the processes that occurred during their birth in protoplanetary disks. This becomes possible as comets draw closer to their suns and their ices begin to sublimate (a process known as “outgassing.”)

Interstellar comets are of particular interest to astronomers because they can tell us a great deal about the formation and evolution of star systems other than our own. When they observed 2I/Borisov, the team detected two types of gas molecules being ejected from the comet: hydrogen cyanide (CHN) and carbon monoxide (CO). The study that describes these findings recently appeared in the journal Nature.

While the team expected to see the former, which is present in 2I/Borisov in similar concentrations to what has been observed in Solar System comets, they were surprised to see large amounts of CO as well. In fact, the CO concentrations were estimated to be 9 to 26 times higher than the average Solar System comet or any comet detected within 2 AU of the Sun (twice the distance between the Earth and the Sun.)

“The comet must have formed from material very rich in CO ice, which is only present at the lowest temperatures found in space, below -420 degrees Fahrenheit (-250 degrees Celsius),” said planetary scientist Stefanie Milam in a recent NRAO press release.

While CO is one of the most plentiful molecules in space and is found inside most comets, there are typically huge variation in terms of its concentration in comets – for reasons which remain unknown. This may be a result of where they formed in the Solar System and/or how often a comet gets closer to the Sun and loses some of its more-easily evaporated ices. As astrochemist Martin Cordiner explained:

“This is the first time we’ve ever looked inside a comet from outside our solar system, and it is dramatically different from most other comets we’ve seen before… If the gases we observed reflect the composition of 2I/Borisov’s birthplace, then it shows that it may have formed in a different way than our own solar system comets, in an extremely cold, outer region of a distant planetary system.”

In all previous cases where ALMA was used to study protoplanetary disks, those disks were found around Sun-like stars. At the same time, many disks extended far beyond where comets in the Solar System are believed to have formed and contained large amounts of extremely cold gas and dust. While the team can only speculate at this point, they believe it is possible that 2I/Borisov came from one of these larger disks.

Given the speed with which it traveled through our Solar System (33 km/s; 21 mps), astronomers suspect that 2I/Borisov was likely to have been kicked out of its host system by gravitational interaction – possibly from a passing star or a giant planet. After that, it is thought to have spent millions or billions of years travelling through the extreme cold of interstellar space before arriving in our Solar System.

2I/Borisov was discovered on August 30th, 2019 by amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov, who it was named in honor of. The only other insteallr object observed – 1I/’Oumuamua – was already on its way out of the Solar System when it was first detected, which made it very difficult to study the object and determine if it was an asteroid, a comet, a fragment of a comet, or something else entirely (like an alien spacecraft or derelict).

In 2I/Borisov’s case, the presence of an active gas and dust coma surrounding it confirmed that it was the first known interstellar comet to ever be observed. The fact that it’s composition is unlike that of comets observed in the Solar System only makes it more appealing for researchers, and is an invitation to find more interstellar comets. As Milam put it:

“2I/Borisov gave us the first glimpse into the chemistry that shaped another planetary system. But only when we can compare the object to other interstellar comets, will we learn whether 2I/Borisov is a special case, or if every interstellar object has unusually high levels of CO.”

In addition to the many ground-based and space-based telescopes that will be on the lookout for interstellar asteroids and comets in the future, there is also compelling evidence that many interstellar objects that arrived in the past ended up staying here. There are even proposals in place to send a spacecraft to rendezvous with an interstellar object in the future, like the ESA’s Comet Interceptor.

There’s no telling when the next interstellar comet or asteroid will pass through our Solar System, or whether or not we will be able to study it up-close using a spacecraft. One thing that is certain is that any future visitors will offer astronomers the opportunity to learn more about other star systems, like their compositions and how planets form within them.

The international team behind this study included members from the Laboratoire d’Etudes Spatiales et d’Instrumentation en Astrophysique (LESIA), the STAR Institute, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), the Institut de RAdioastronomie Millimétrique (IRAM), multiple universities, the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and NASA HQ.

Since the team led by Cordiner and Milam made their observations, 2I/Borisov appears to have split into two objects (aka. “calving.”) This occurred in late March as the comet was making its way back into interstellar space. The venerable Hubble was able to catch a final glimpse of “Little Boris and Big Boris” as they departed our Solar System, perhaps never to be seen again.