We're waiting patiently for telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope to see first light, and one of the reasons is its ability to study the atmospheres of exoplanets. The idea is to look for biosignature s: things like oxygen and methane. But a new study says that exoplanets with hydrogen in their atmospheres are a good place to seek out alien life.

This idea goes against the grain. Hydrogen is not commonly thought of as a biosignature, even though some bacteria produce it as they break down organic matter. But there are other reasons that make planets with hydrogen in their atmospheres solid targets in the search for life.

The new paper is titled " Laboratory studies on the viability of life in H2-dominated exoplanet atmospheres." The lead author is Sara Seager, a well-known astrophysicist and planetary scientist at MIT. The paper is published the journal Nature Astronomy.

"There’s a diversity of habitable worlds out there, and we have confirmed that Earth-based life can survive in hydrogen-rich atmospheres."Sara Seager, Lead Author, MIT.

As Seager and her co-authors point out, hydrogen atmospheres are a desirable place to look for signs of life. It's not because the hydrogen itself necessarily signals the presence of life. It's because hydrogen is so much lighter than elements like nitrogen and oxygen, which are present in Earth's atmosphere. That means that hydrogen atmospheres extend much further into space, and are more easily studied with our telescopes.

As the authors write, "The most observationally accessible rocky planet atmospheres are those dominated by molecular hydrogen gas, because the low density of H2gas leads to an expansive atmosphere."

That statement is not in any way controversial. But can life survive in an environment like that? "The capability of life to withstand such exotic environments, however, has not been tested in this context," the researchers write. And that brings us to the meat of the study.

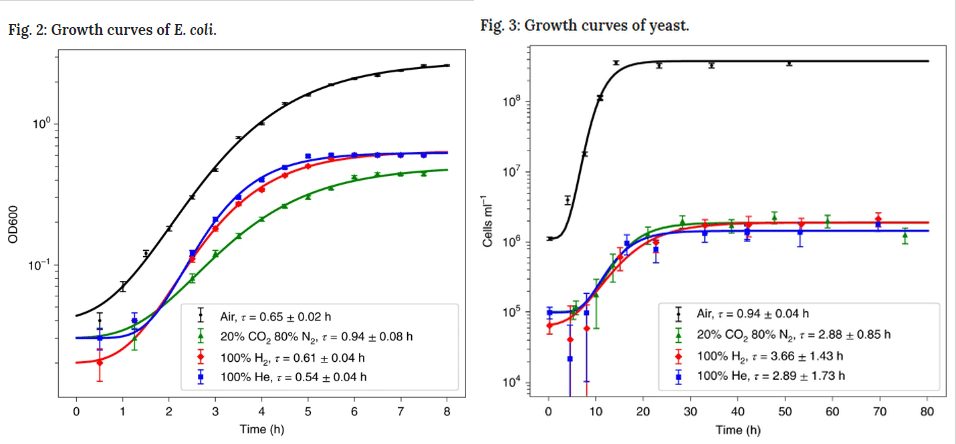

"We demonstrate that single-celled microorganisms (*Escherichia coli* and yeast) that normally do not inhabit H2-dominated environments can survive and grow in a 100% H2atmosphere," they write. From there the scientists point out the variety of gases that microorganisms can produce in a hydrogen atmosphere.

"We also describe the astonishing diversity of dozens of different gases produced by *E. coli*, including many already proposed as potential biosignature gases..." write Seager and her colleagues. That includes a laundry list of biosignatures: nitrous oxide, ammonia, methanethiol, dimethylsulfide, carbonyl sulfide and isoprene.

The scientists point out that these are lab results, and they say that lab experiment like theirs can help identify which alien atmospheres might host detectable life.

In a press release, Seager said: "There's a diversity of habitable worlds out there, and we have confirmed that Earth-based life can survive in hydrogen-rich atmospheres. We should definitely add those kinds of planets to the menu of options when thinking of life on other worlds, and actually trying to find it."

In Earth's deep past, the atmosphere was much different than today. There was no oxygen, and the atmosphere contained carbon dioxide, methane, and a small amount of hydrogen. Then came what's known as the Great Oxygenation Event (GOE), or as some dramatic types like to call it, "The Oxygen Holocaust."

During the GOE, the history of the Earth changed course. Around 2.4 billion years ago, evidence shows that molecular oxygen began to accumulate in the atmosphere. That oxygen had a biological source: cyanobacteria.

Cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, were among Earth's first life-forms. As they changed the atmosphere to an oxidizing atmosphere, other life went extinct. In fact, almost all life on Earth at the time went extinct, while at the same time, the way was paved for multicellular life.

But even after the GOE, hydrogen lingered in Earth's atmosphere. And some ancient lines of life, including methanogens, consume it. Methanogens live in extreme environments on Earth, places like hot springs, deep in desert soil, deep in ice, and in hydrothermal vents. There, they eat hydrogen and carbon dioxide, and produce methane.

Methanogens are well-studied, and scientists know that they can grow in 80% hydrogen atmospheres, at least in labs. But according to the press release, there aren't many studies exploring how other microbes can tolerate hydrogen-rich environments.

"We wanted to demonstrate that life survives and can grow in an hydrogen atmosphere," Seager says.

In the paper the team outlines how rocky exoplanets can have hydrogen in their atmospheres:

- Super-Earths can have hydrogen in their atmospheres from out-gassing, or from capturing it from their protoplanetary disks as they form. "Super-Earth exoplanets may have captured a H2–He atmosphere from the protoplanetary disk, in contrast to planets that formed an H2atmosphere from out-gassing," the authors write.

- Small planets less than about 1.7 Earth radii may have formed with H2atmospheres and maintained them, provided the planets contain enough Fe from formation, provided the planet also contains water and the water and the Fe react.

- Planets further from their stars may be able to hold onto their hydrogen, which can be stripped away by stellar radiation.

"Given the facts that rocky exoplanets with H2-dominated atmospheres likely exist, that such planet atmospheres are more easily observed than N2- or CO2-dominated atmospheres, and that the next-generation telescopes with the capability to study rocky planet atmospheres are coming online in the next several years, it is important to assess the viability of life for such planets," the authors write.

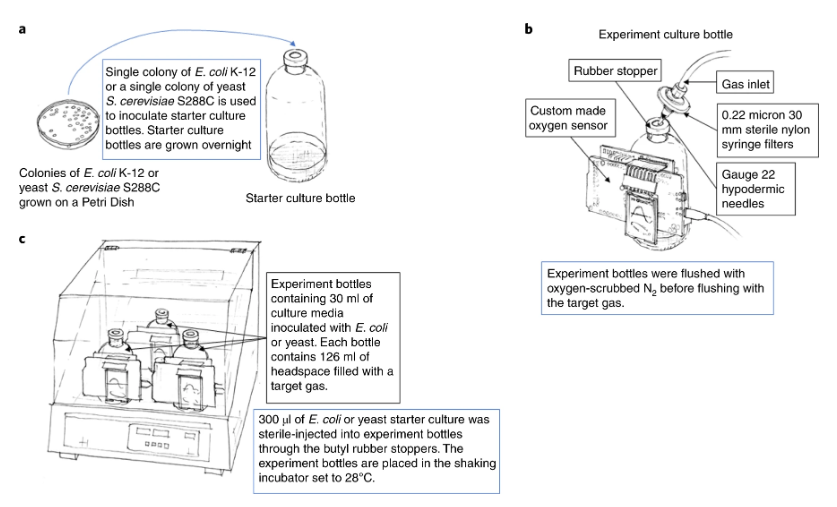

The team focused on two organisms to see if they could be viable in a 100% hydrogen atmosphere: the simple prokaryote *Escherichia coli*, and a more complex eukaryote, yeast. Both are well-understood organisms that scientists have studied for a long time. That makes it easier to design experiments.

The team grew separate cultures of both yeast and *E. coli*. Then they placed the cultures inside bottles containing a soup of nutrient-rich materials that the organism could feed off. Then, they removed the oxygen from the bottles and replaced it with different gases of interest, for example 100% hydrogen.

Each hour, they extracted a sample from the bottles, and counted the living microbes. The sampling process lasted for up to 80 hours. At first, there was a population boom, as the microbes quickly consumed the nutrients. Then the population leveled off. It then remained stable as new microbes replaced dead ones.

"We consider a pure 100% H2atmosphere as a control; if life can survive in a 100% H2atmosphere then it can also survive in an H2-dominated atmosphere," the authors write. "We show that a 100% H2atmosphere has no detrimental effects on microorganisms that do not normally inhabit H2-rich conditions." In nature, there's likely no planets with 100% hydrogen atmospheres.

"I don’t think it occurred to astronomers that there could be life in a hydrogen environment."Sara Seager, Lead Author, MIT.

Nobody on the team was surprised by the results, and they didn't expect anyone else to be surprised, either. Hydrogen is not toxic to organisms, though it is not an inert gas. Still, the experiment is important to prove the point.

"It's not like we filled the headspace with a poison," Seager says. "But seeing is believing, right? If no one's ever studied them, especially eukaryotes, in a hydrogen-dominated environment, you would want to do the experiment to believe it."

Of course, the hydrogen itself is not a food source for the microbes. That wasn't the intent of the experiment. The researchers wanted to show that life could exist in a hydrogen environment, provided they had a food source, and that a hydrogen atmosphere doesn't preclude the possibility of life.

"I don't think it occurred to astronomers that there could be life in a hydrogen environment," says Seager.

The key to this study isn't that hydrogen supports life. It's that hydrogen atmospheres are much easier to see with telescopes, because they're more expansive. So when looking for targets to find biosignatures, it might be advisable to survey planets with hydrogen atmospheres.

""It's kind of hard to get your head around, but that light gas just makes the atmosphere more expansive," Seager explains. "And for telescopes, the bigger the atmosphere is compared to the backdrop of a planet's star, the easier it is to detect."

Universe Today

Universe Today