In March of 2019, NASA was directed by the White House to land human beings on the Moon within five years. Known as Project Artemis, this expedited timeline has led to a number of changes and shakeups at NASA, not the least of which has to do with the deprioritizing of certain elements. Nowhere is this more clear than with the Lunar Gateway, an orbital habitat that NASA will be deploying to cislunar space in the coming years.

Originally, the Gateway was a crucial part of the agency's plan to create a program of "sustainable lunar exploration." In March of this year, NASA announced that the Lunar Gateway is no longer a priority and that Artemis will rely on an integrated lunar lander instead. However, NASA still hopes to build the Gateway, and according to a recent interview with ArsTechnica, this could be done with the help of SpaceX and the *Falcon Heavy*.

In the course of the interview, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine and Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations Doug Loverro reiterated that the Gateway is essential to NASA's long-term plans. This includes lunar exploration and the creation of a permanent outpost there (the Lunar Habitat), but also their plan of mounting crewed missions to Mars.

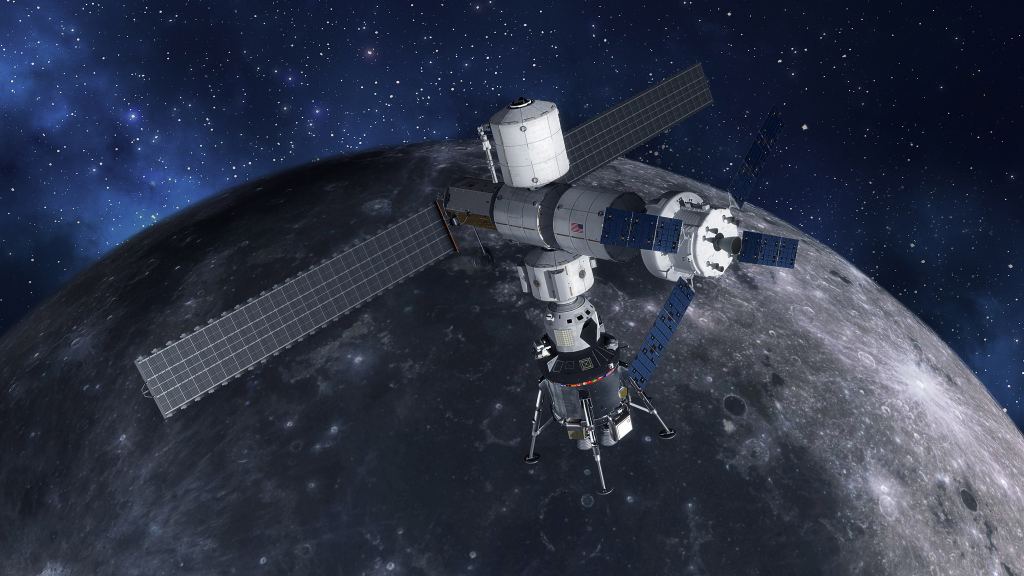

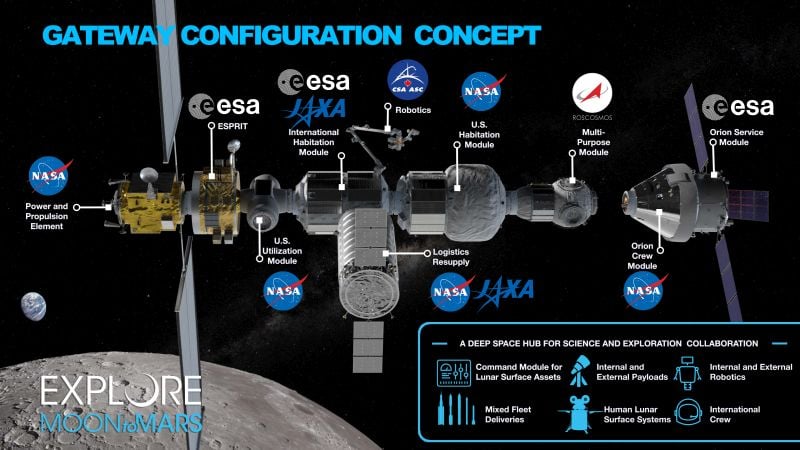

At present, NASA's plan is to launch the first two elements of the Gateway in 2023 as a single integrated payload using a commercial launch provider. This would form the nucleus of the Gateway, known as the "Mini-space station Gateway, which includes the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) - built by Maxar Technologies - and the pressurized Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO), built by Northrop Grumman.

Originally, NASA hoped to have the PPE module ready by 2022 so that it could be launched as part of the Artemis 2* mission. But as Loverro explained, they now plan to send it up a year later using a commercial rocket - likely SpaceX's Falcon Heavy*:

"We assured ourselves that it could be done with the Falcon Heavy. We haven't selected the launch vehicle yet, but we had to assure ourselves that there would be at least one vehicle for it. And so we know the Falcon Heavy can do it, and we know that because they have to meet an Air Force Department of Defense requirement for an extended fairing. So there could be more than one option, but we had to verify at least one."

The design of the PPE calls for a 50-kilowatt solar electric propulsion (SEP) spacecraft that will serve as a mobile command and service module for missions to the lunar surface, as well as a communications relay. The HALO module, meanwhile, will serve as the crew cabin and hub of the Gateway, connecting the PPE and Orion spacecraft with other elements.

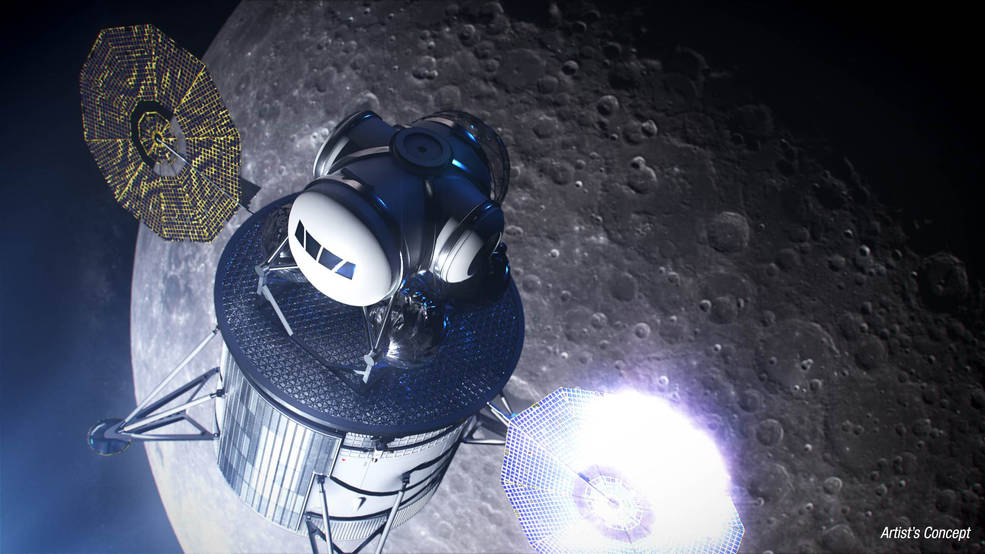

This includes the Human Landing Systems (HLS), a reusable lunar lander that could be deployed from either the Orion spacecraft or the Gateway. Recently, NASA selected three major contractors to develop this crucial element (SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Dynetics) through their Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP-2) program.

According to Loverro, assembling the two initial elements of the Gateway on the ground before launching them will reduce risk and save NASA money on launch costs. In the meantime, NASA continues to work with other contractors to develop elements of the Gateway that will be integrated over time.

Beyond the PPE and HALO modules, there's the International Habitation Module (iHAB) currently being developed by European aerospace contractors Airbus and OHB, the ESPRIT service module being built by the ESA and JAXA, the Gateway Airlock Module being built by Roscosmos for EVAs and docking, and a series of Logistic Modules used to refuel and resupply spacecraft using a robotic arm developed by the CSA.

Dan Hartman, NASA's program manager for the Gateway, commented on these preparations in a separate interview with Ars, saying:

"We have the International-HAB, which we call the I-HAB, which is kind of a combination with ESA in the lead but with JAXA supplying components for that. The Canadians are providing the robotic devices, which is certainly the bigger arm, and then they'll have some dexterous capability as well. One element that we are still kind of under a lot of discussion on is the airlock, and we've reached out to Roscosmos for that."

For the sake of streamlining the process of building the Gateway, Loverro also states that NASA has "also eliminated two docking assemblies, one propulsion service module, an extra power system, and several other major assemblies." These, as well as the decision to de-prioritize the construction of the Gateway, are all in keeping with reducing the risks associated with Artemis.

More to the point, these decisions are key to ensuring that the all-important *Artemis III* - which will see the first woman and next man land on the Moon by 2024 - happens on time and on budget. So while the Gateway may not be operational for that mission, NASA still plans to build it and use to fulfill their long-term goals.

At present, they're relying more on commercial partnerships to make that happen, rather than betting on the completion of the Space Launch System (SLS) and other systems by then. In summation, we are going back to the Moon and we plan to stay, just not as it was originally planned or on the same timeline.

*Further Reading: ArsTechnica*

Universe Today

Universe Today