Personnel at NASA and the DLR have been working for months to get InSight's Mole working. They're at a disadvantage, since the average distance between Earth and Mars is about 225 million km (140 million miles.) They've tried a number of things to get the Mole into the ground, and they may finally be making some progress.

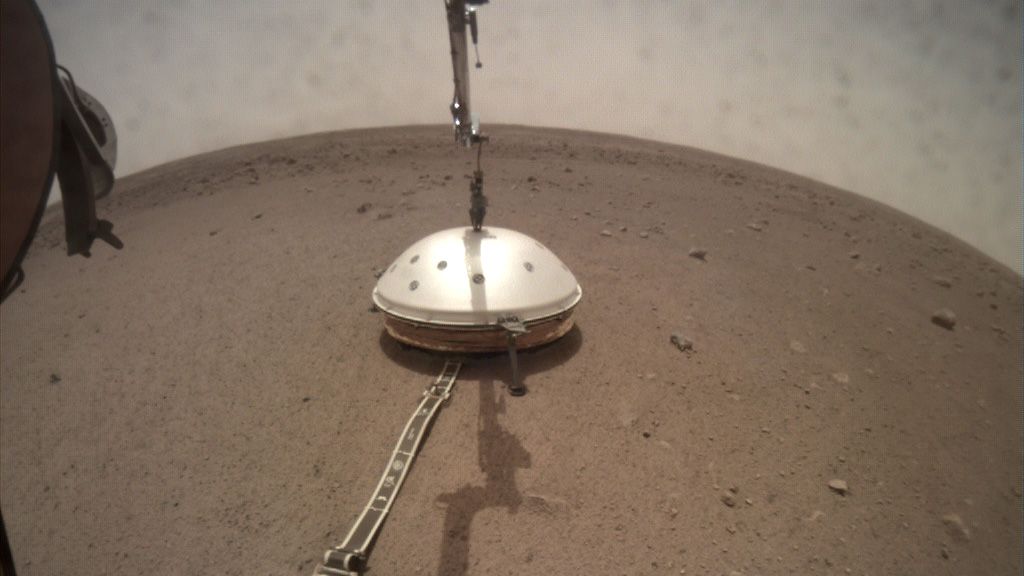

The InSight lander (Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) is a joint mission between NASA and the DLR, or German Aerospace Center. One of the lander's primary instruments is the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package, or 'Mole', so-called because it needs to burrow into the ground to fulfill its mission. The Mole's job is to measure the heat that flows from the planet's interior to the surface.

Trouble started when it became clear that the sub-surface soil near the lander was dura-crust. The duracrust is sand cemented together by salt, and it's in a layer about 20 cm (8 in.) thick. After the Mole made some initial progress, it stalled. The Mole relies on soil falling in around its hole as it hammers its way into the surface, giving it the necessary friction to penetrate.

But the dura-crust refused to fall into the hole.

NASA and the DLR tried using the scoop on the end of the instrument arm to push soil into the Mole's hole, but that didnt work.

Personnel also tried exerting sideways pressure on the Mole, in an attempt to provide the necessary friction. But that didn't work, either.

There's no way to reposition the Mole to a new spot, in hopes of avoiding the troublesome duracrust. It's too delicate to be re-deployed safely, so engineers are forced to try everything else.

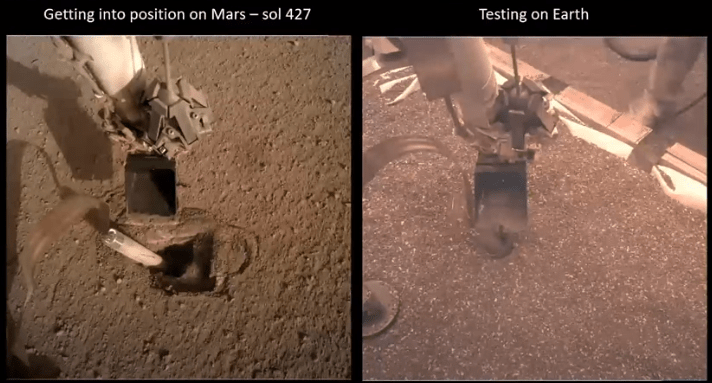

Now, mission personnel are using the instrument arm's scoop to apply downward pressure on the Mole. That's a tricky operation, with a wiring harness protruding from the top of the Mole in a vulnerable spot. Damage the harness, and the whole experiment is probably over.

They began this procedure back in March, and saw some progress.

On May 4th, a representative from the DLR spoke at a webinar as part of the European Geosciences Union General Assembly. Tilman Spohn is the principal investigator for the Mole, and he gave an update. "The mole is going down by its hammering mechanism, but it is aided by the push of the scoop that balances the force of the recoil," Spohn said.

It's progress, which is great, but it's very slow progress. That's because they need to frequently re-position the instrument arm and its scoop. "That is a very tedious operation," he said. "We can only go like 1.5 centimeters (0.6 in) at a time before we have to readjust."

Then there's the problem of the angle. The Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package was designed to penetrate the surface at a vertical angle. But instead, its at a 30 degree angle, adding to the difficulties.

"It's not something we like to see," Spohn said. But if the mole is able to get its whole instrument body to penetrate the surface, that angle might correct itself.

As if things aren't complicated enough, there's another problem. The Mole penetrates with a hammering motion. As it hammered at the ground without making any progress, it compacted the soil directly underneath it. Now the Mole must contend with that compacted soil.

There's no new word on how long it'll take the Mole to penetrate far enough to do its job. It was designed to penetrate down to 5 meters (16 ft) but is able to do some work at less depth, perhaps about 2 meters (6 ft.) But with progress this slow, even getting to 2 meters could take a long time.

Spohn didn't provide an update on the timing. But back on April 17th, NASA's principal investigator for the InSight mission, Bruce Banerdt, did give an update.

"We anticipate that we'll have the mole down flush with the ground within another month or two months," he said at a

"At that point, it's either going to be able to go on its own or not."

Universe Today

Universe Today