The Antarctic Peninsula is the northernmost part of Antarctica, and has the mildest climate on the continent. In January, the warmest part of the year, the temperature averages 1 to 2 °C (34 to 36 °F). And it’s getting warmer.

Those warm temperatures allow snow algae to grow, and now scientists have used remote sensing to map those algae blooms.

The algae map is part of a study examining algae and climate change. Since the land-based ecosystem is strongly limited by the cold climate, these blooms, which grow on snow, represent an important part of the ecosystem.

The new study is titled “Remote sensing reveals Antarctic green snow algae as important terrestrial carbon sink.” The lead author is Dr Matt Davey, from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Plant Sciences. The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

“This is a significant advance in our understanding of land-based life on Antarctica, and how it might change in the coming years as the climate warms.”

Lead Author Dr. Matt Davey, University of Cambridge.

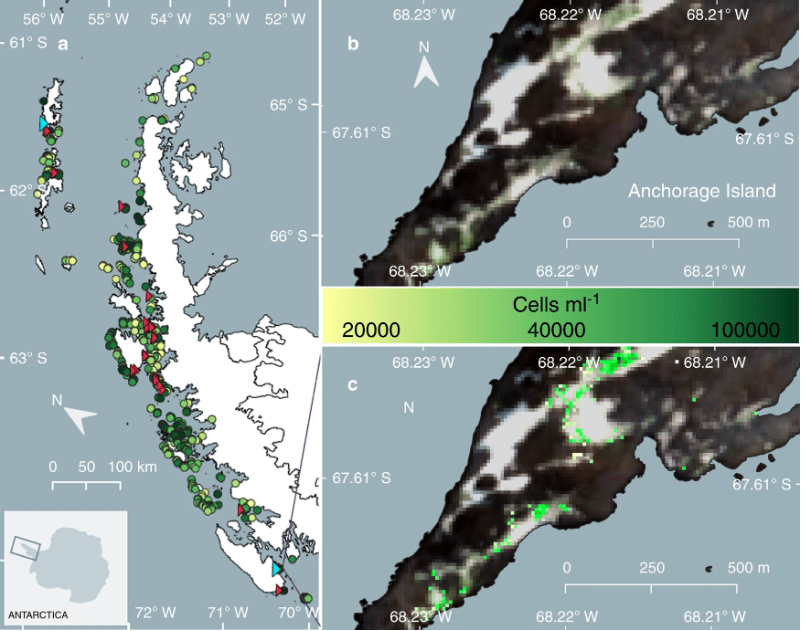

For two summers, the team of researchers behind this work collected both satellite data and ground observations on Antarctic algae blooms. The individual organisms are microscopic, but collectively they’re visible from space. Though the individual blooms only cover a few square meters, collectively they cover almost 2 sq. km.

That might not sound like much, until you put it in terms of how much atmospheric carbon they absorb.

“We identified 1679 separate blooms of green algae on the snow surface, which together covered an area of 1.9 km2, equating to a carbon sink of around 479 tonnes per year,” said lead author Davey in a press release. For comparison, this is the same amount of carbon emitted by about 875,000 average internal combustion car journeys in the UK.

It’s warmer temperatures that allow the algae to bloom, and the Antarctic Peninsula is the warmest part of the continent. But algae needs food, too. And in the Antarctic that food is mostly in the form of penguin excrement. Blooms were found near other bird colonies, and where seals come ashore in numbers. But over 60% of the 1679 blooms the team found were within 5 km (3.1 miles) of a penguin colony.

As the study says, “Marine fauna are a potential source of nutrients for Antarctic snow algae, with faeces at seal haul-outs, penguin colonies and nesting sites for other birds providing hot spots of nitrogen and phosphate in an otherwise typically oligotrophic environment.”

“This is a significant advance in our understanding of land-based life on Antarctica, and how it might change in the coming years as the climate warms,” said lead author Davey. “Snow algae are a key component of the continent’s ability to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis.”

The location of these algae blooms will change over time, also as a consequence of climate change. The majority of the blooms are on smaller, low-lying islands without any high ground. As the climate warms, these island may lose their snow coverage.

But the bulk of the algae is contained in a smaller number of larger blooms. They’re located in areas where they can move to higher ground as the lower-lying snow melts away. As a result, the algae will increase as the climate continues to warm.

“As Antarctica warms, we predict the overall mass of snow algae will increase, as the spread to higher ground will significantly outweigh the loss of small island patches of algae,” said lead author Gray.

The IPCC (International Panel on Climate Change) forecasts a global temperature increase of 1.5 Celsius, and that means that “the 0°C isotherm will increase in elevation and that positive degree days will become more commonplace and occur further to the south,” according to the authors. They also write that “This will likely open up new snow for colonisation by green snow algae, should an appropriate dispersal mechanism allow transfer to new areas.”

It’s unclear whether the amount of nutrients available from penguin colonies and other sources will change with rising temperatures. From the study: “The impact warming would have on marine nutrient supply to the snowpack is less clear, as marine vertebrates have shown varying degrees of plasticity in response to a changing Antarctic environment.”

Of course, as the climate warms due to increasing atmospheric CO2 levels, not only will algae bloom—given sufficient nitrogen and phosphorous for food—but the algae will also absorb more carbon, becoming a more significant carbon sink. The number of 479 tonnes of carbon per year will likely rise significantly.

In fact, the 479 tonne figure is likely already too low. This study only measure green algae, but there’s also orange and red snow-algae, which this study didn’t measure. The team hopes to do another study that measure those algae blooms, as well as covers the entire Antarctica, rather than just the Antarctic Peninsula.

Though the bulk of Antarctica is frozen and lifeless, the coastal areas can be quite rich in life. Mosses and lichens are abundant in spots. They’re the two largest groups of photosynthetic organisms in Antarctica, and have been studied more than algae. They play an important role in carbon cycling, but as this study shows, they’re not alone.