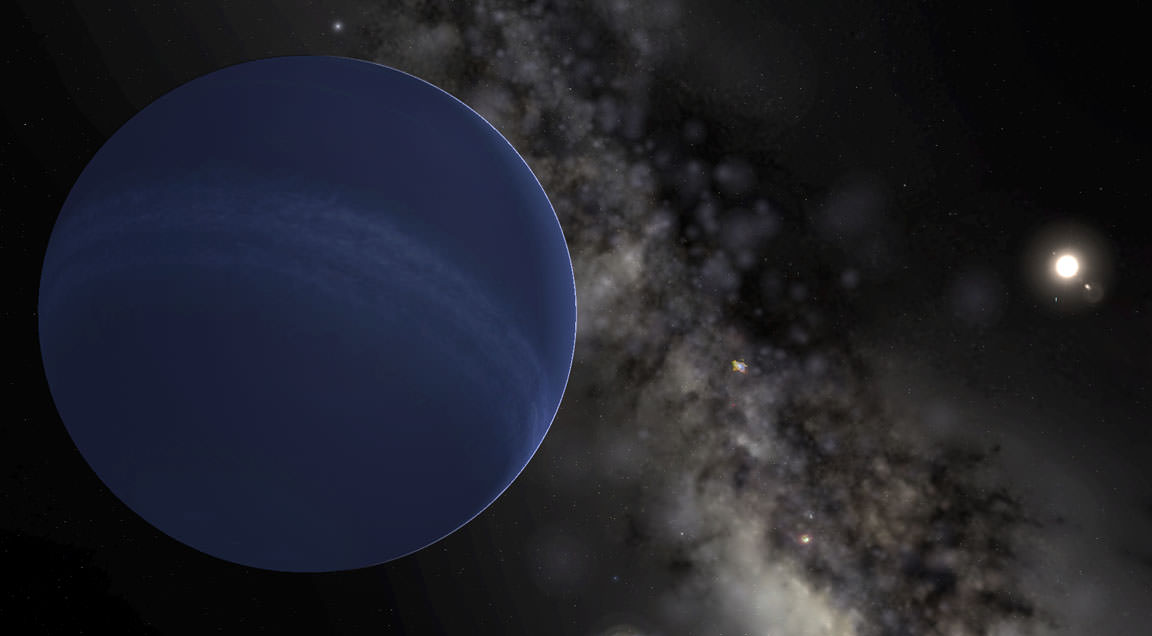

Oh Planet Nine, when will you stop toying with us?

Whether you call it Planet Nine, Planet X, the Perturber, Jehoshaphat, “Phattie,” or any of the other proposed names—either serious or flippant—this scientific back and forth over its existence is getting exhausting.

Is this what it was like when they were arguing whether Earth is flat or round?

Though it’s never been observed, there’s been evidence that there’s another planet out there. That evidence is largely based on clustering of distant objects, way out in the reaches of our Solar System: Kuiper Belt Objects (KBO).

KBOs are chunks of material that date back to the early days of the Solar System. They just never got swept up in planetary formation, and now there they are. They range in size from boulders up to larger objects 2,000 km (1200 miles) across.

Some of those KBOs have some puzzling orbits. They’re very elliptical, and tilted, just like Pluto. Those orbits have been presented as evidence of an undiscovered large planet out there, unseen, yet shepherding these KBOs on their unusual orbits with its great mass.

Samantha Lawler is an assistant Professor of Astronomy at the University of Regina, Canada. She’s studied distant KBOs and Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNO) in an effort to understand the processess, and possible large planets, that shape the distant Solar System. In a recent article at The Conversation, she outlined the current state of evidence regarding the existence of Planet Nine.

According to Lawler, the astronomy community doubts that there is a Planet Nine.

“…the Planet Nine theory does not hold up to detailed observations.”

Samantha Lawler, Ass’t. Professor of Astronomy, University of Regina

This Planet Nine business started around 2016, when astronomers Mike Brown and Konstantin Batygin hypothesized the existence of Planet 9. They discovered the aforementioned KBOs with those strange, tilted, elliptical orbits. Evidence of another large, undiscovered planet, they suggested. It would be like an exoplanet Super-Earth, they suggested, and its mass was responsible for those strange, unexplained orbits.

Brown and Batygin were cautious, like the good scientists that they are. But they said, rightly so at the time, that the hypothesis was solid. “Though this analysis does not say anything directly about whether Planet Nine is there, it does indicate that the hypothesis rests upon a solid foundation,” Brown said at the time.

Since then, there’s been a lot of talk and conjecture about Planet Nine, some of it serious, some of it not.

Now Lawler, who has studied the distant Solar System and its resident objects, says it’s time to put Planet Nine to bed.

“The discoveries from the most successful Kuiper Belt survey to date, the Outer Solar System Origins Survey (OSSOS), suggest a sneakier explanation for the orbits we see,” she writes. And it all has to do with Neptune.

“Mathematical calculations and detailed computer simulations have shown that the orbits we see in the Kuiper Belt can only have been created if Neptune originally formed a few AU closer to the sun, and migrated outward to its present orbit,” she writes. “Neptune’s migration explains the pervasiveness of highly elliptical orbits in the Kuiper Belt, and can explain all the KBO orbits we’ve observed,” she wrote, except for a handful.

Proponents of Planet Nine proposed that it’s about 10 times more massive than Earth. They say only something like that is likely to account for the extreme-orbit KBOs that were all discovered in one quadrant. But Lawler says there’s something else going one here: observational bias.

Astronomers expect to find a variety of orbits among objects, unless something is acting on them to shape them the same way. “Finding several extreme KBOs on orbits pointed in the same direction was a hint that something was going on,” she writes. She points out that two separate groups of researchers presented studies pointing to the existence of the orbit-shaping Planet Nine. And there’ve been multiple studies saying only a Planet Nine could be responsible.

But those conclusions were a little premature, according to Lawler. After four years, she points out in her article, there’s no direct evidence for Planet Nine: only indirect evidence.

Lawler is part of a collaboration of scientists using the Canada-France Hawaii Telescope to look for KBOs. For five years they looked, and found more than 800 new ones. That doubled the number of KBOs with known orbits. In short, our understanding of the outer Solar System and its denizens just got a lot more detailed.

These objects are incredibly difficult to see. They’re way out there, and the most distant are over 1000 astronomical units away. Even though some of them are over 100 km in size, the great distance means they’re nearly invisible. And since they follow highly elliptical orbits, they spend most of their time a great distance from the Sun, adding to the observational challenge.

Herein lies the observational bias that Lawler says is clouding our understanding of the distant Solar System. She writes: “This means that the KBOs on elliptical orbits are particularly hard to discover, especially the extreme ones that always stay relatively far from the sun. Only a few of these have been found to date and, with current telescopes, we can only discover them when they are near pericentre — the closest point to the sun in their orbit.”

And Lawler drives the point home even more clearly, explaining that “This leads to another observation bias that has historically been ignored by many KBO surveys: KBOs in each part of the solar system can only be discovered at certain times of year. Ground-based telescopes are additionally limited by seasonal weather, with discoveries less likely to happen during when cloudy, rainy or windy conditions are more frequent. Discoveries of KBOs are also much less likely near the plane of the Milky Way galaxy, where countless stars make it difficult to find the faint, icy wanderers in telescopic images.”

“Many beautiful and surprising objects remain to be discovered in the mysterious outer solar system, but I don’t believe that Planet Nine is one of them.”

Samantha Lawler, University of Regina.

But knowing these biases in advance, and accounting for them in their five-year survey, has cleared some things up. Lawler says that their discovery of additional extremely distant KBOs with a uniform distribution shows that there really isn’t a clumping. And another, additional survey found more KBOs with uniform distribution.

To clarify their findings, Lawler and her colleagues did some simulations. Those simulations showed that “if observations are made only in one season from one telescope, extreme KBOs will naturally only be discovered in one quadrant of the solar system,” Lawler wrote.

Lawler says that all of the new observational evidence simply doesn’t add up to Planet Nine.

“These simulations predict that there should be many KBOs with pericentres as large as the two outliers, but also many KBOs with smaller pericentres, which should be much easier to detect,” she writes. “Why don’t the orbit discoveries match the predictions? The answer may be that the Planet Nine theory does not hold up to detailed observations.”

“Many beautiful and surprising objects remain to be discovered in the mysterious outer solar system, but I don’t believe that Planet Nine is one of them,” Lawler concludes.

As for the name of this object, in the seemingly unlikely event that it is ever confirmed, some scientists have some strong ideas about that. In 2018, planetary scientist Alan Stern, who is the principal investigator for the New Horizons mission among other things, signed a letter along with 34 other scientists objecting to the very unscientific name of “Planet Nine.”

All those other names “should be discontinued in favor of culturally and taxonomically neutral terms for such planets, such as Planet X, Planet Next, or Giant Planet Five,” they wrote.

I guess “Phattie” is out of the question.

More:

- The Conversation: Why astronomers now doubt there is an undiscovered 9th planet in our solar system

- Universe Today: Evidence Mounts for the Existence of Planet Nine

- Universe Today: The Record for the Most Distant Object in the Solar System has been Shattered. Introducing FarFarOut at 140 Astronomical Units

The pre-discovery naming question is really getting out of hand. Planet X is hardly a neutral term, nor is it unique.

I’m not sure Lawler claims the Planet Nine collaboration is premature, but as far as I understand her article she is. The paper Lawler is coauthor of and references for claiming isotropy in the original Dark Energy Survey data rely, unless I’m mistaken, on year P1-P3 data.

Now the DES collaboration year P4 data added 3 new extreme perihelion KBOs to their earlier 4. But they still can’t reject Planet Nine.

On the other hand there was ~ 10 more such KBOs in the Planet 9 collaboration work that claimed they found a planet.