NASA’s Mars Odyssey Orbiter doesn’t get a lot of headlines lately. It was sent to Mars in 2001, to detect the presence of water and ice on Mars, or the past presence of it. It also looked at Mars’ geology and radiation. It’s been doing its job without a lot of fanfare.

Now Odyssey’s infrared camera has given us three new images of Mars’ moon Phobos.

Odyssey’s infrared camera is called THEMIS. It stands for Thermal Emission Imaging System. THEMIS works in the infrared and in the visual, and when paired with Odyssey’s Thermal Emission Spectrometer, it can help refine the spectrometer’s data on the distribution of minerals on the surface of Mars.

But these new images were all of Phobos, the largest of Mars’ two moons.

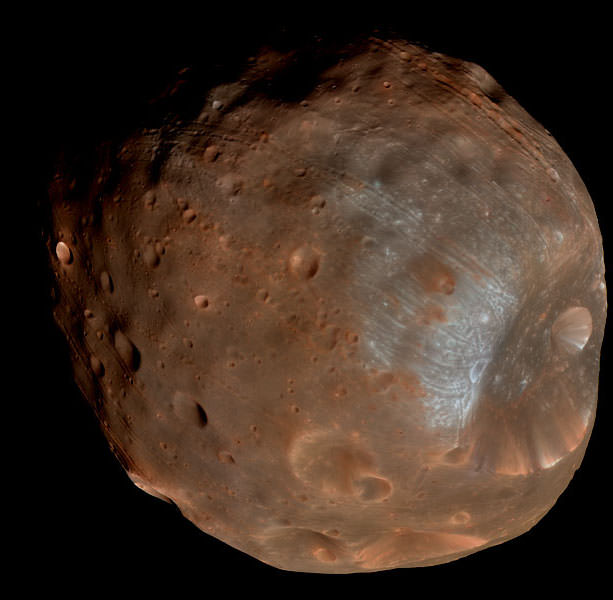

Phobos is Mars’ innermost moon. Like its smaller sibling Deimos, Phobos is a lumpy, misshapen piece of rock, and its comparison to a potato is hard to avoid. Its most well-known feature is the Stickney Crater, seen in the image below. Its surface also has a series of long grooves that appear to stem from Stickney. The Stickney Crater itself is 9 km (5.6 miles) in diameter, while Phobos is about 22.5 km (14 miles) in diameter.

The cause of the crater is obvious. Something impacted the tiny moon. And according to a 2018 paper, that impact was responsible for the grooves too. That paper showed that debris from the impact rolled along Phobos’ surface, creating the grooves.

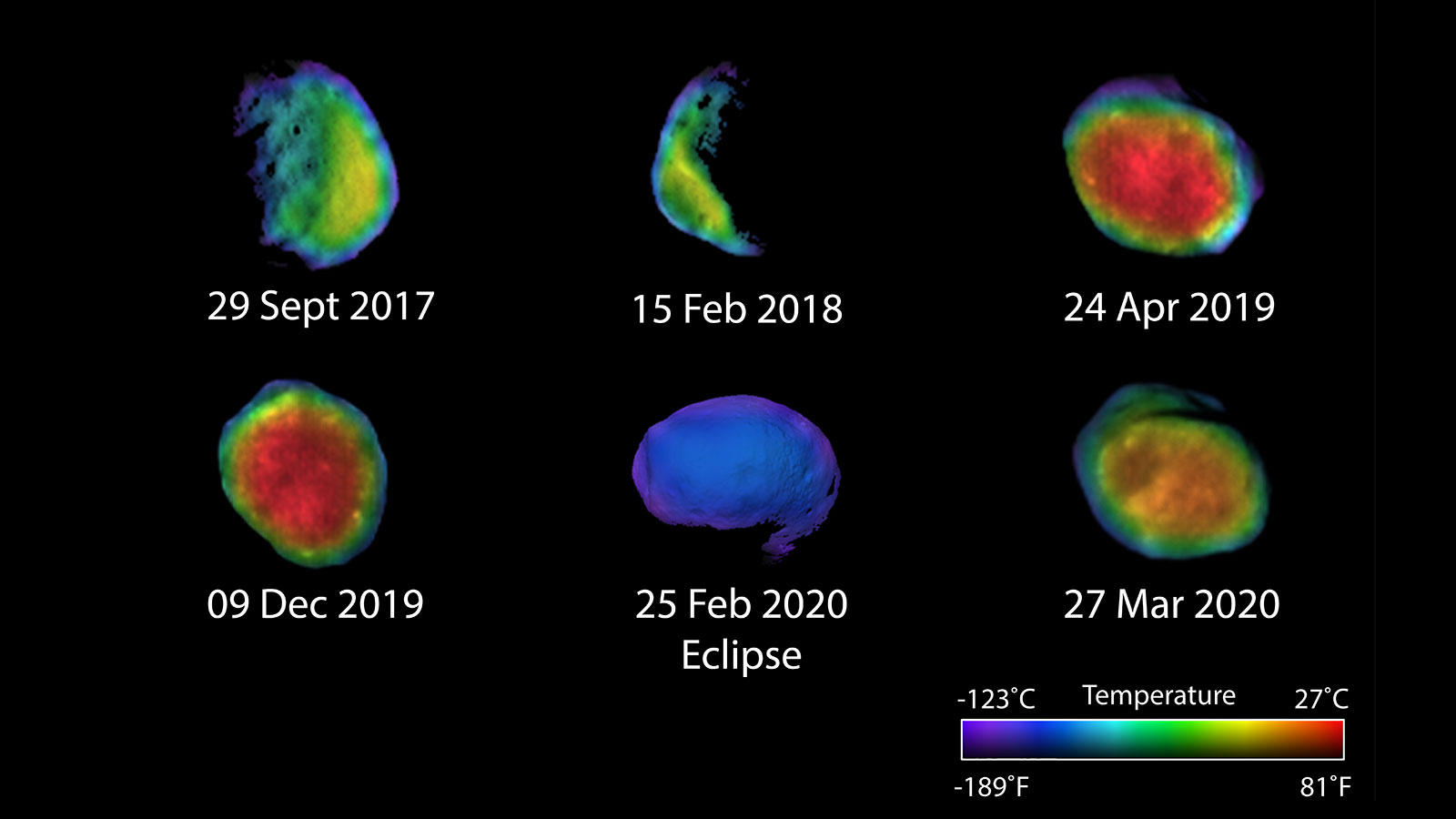

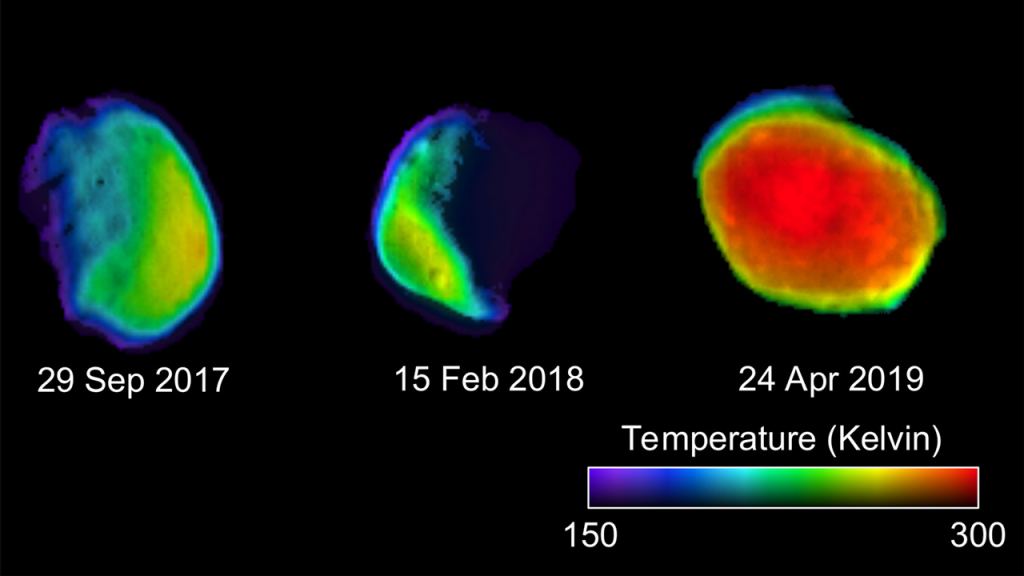

These three new images were taken through the past winter and spring, and show the moon as it moves through Mars’ shadow. They were combined with three older, similar images of Phobos. By measuring the temperature variations on Phobos’ surface as it moves in and out of shadow, the images can tell scientists about Phobos’ composition. These images and their data may not be conclusive, but researchers hope it sheds some light on the debate over Phobos’ origin: is it a captured asteroid? Or an ancient chunk of Mars sent into orbit after another body collided with Mars? Does it have another origin?

“This new image is a kind of temperature bullseye — warmest in the middle and gradually cooler moving out,” said Jeffrey Plaut, Odyssey project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, which leads the mission. “Each Phobos observation is done from a slightly different angle or time of day, providing a new kind of data,” Plaut, describing the first three images.

The different views provide better looks at different aspects of Phobos. The full moon view is better for studying material composition, whereas half-moon views are better for looking at surface textures.

“With the half-moon views, we could see how rough or smooth the surface is and how it’s layered,” said Joshua Bandfield, a THEMIS co-investigator and senior research scientist at the Space Sciences Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “Now we’re gathering data on what minerals are in it, including metals.” Phobos’ mineral and metal content will be key to eventually determining the origin of the moon.

These images weren’t easy to acquire. Engineers had to figure out a way to flip Odyssey upside down and train its cameras on Phobos.

The images are combined with visual light images taken at the same time. The eclipse image is the exception, which shows how the moon would’ve looked if it wasn’t in complete darkness.

The combined six images show Phobos when it’s waxing, waning, and full.

“We’re seeing that the surface of Phobos is relatively uniform and made up of very fine-grained materials,” said Christopher Edwards of Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, who leads the processing and analysis of the Phobos images. “These observations are also helping to characterize the composition of Phobos. Future observations will provide a more complete picture of the temperature extremes on the moon’s surface.”

These Mars Odyssey images are serving another purpose, too. JAXA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, is planning to send a sample return mission to Phobos in 2024. The ESA is proposing their own sample return mission to the small moon, also in 2024. Those two agencies will need detailed observations of Phobos’ surface to prepare for their missions.

“By studying the surface features, we’re learning where the rockiest spots on Phobos are and where the fine, fluffy dust is,” Bandfield said in a press release. “Identifying landing hazards and understanding the space environment could help future missions to land on the surface.”

Phobos’ origin is still unclear. The captured asteroid theory holds a lot of sway, because both Phobos and Deimos have a lot in common with carbonaceous C-type asteroids, the most common type of asteroid in our Solar System. But a captured asteroid should have a more elongated, elliptical orbit, whereas Phobos’ orbit is closer to circular.

Another theory says that Phobos is a secondary Solar System object. That means that rather than forming at the same time as Mars and taking up a circular orbit, it formed out of another cloud of material long after Mars had already formed.

Another theory says that Phobos, and likely Deimos, are both chunks of Mars, ejected into orbit by a massive impact. That theory says that there may have been many other moons like Phobos and Deimos, but that they’ve fallen back to the surface. Phobos is on its way to colliding with Mars, and will impact the surface within 30 to 50 million years, if it’s not torn apart by tidal forces first.

Other recent observations of Phobos show that it’s highly porous, little more than a rubble pile held together by a crust.

These infrared images and the varying views of Phobos won’t solve the mystery of its origins on their own. But they’re feeding into it.

If JAXA and the ESA successfully return samples of Phobos to Earth, we may finally get our answer.

More:

- Press Release: Three New Views of Mars’ Moon Phobos

- Previous Press Release: Why This Martian Full Moon Looks Like Candy

- Universe Today: Mars Express Takes Photos of Phobos as it Flies Past