It's a captivating idea: build an interstellar ark, fill it with people, flora, and fauna of every kind, and set your course for a distant star! The concept is not only science fiction gold, its been the subject of many scientific studies and proposals. By building a ship that can accommodate multiple generations of human beings (aka. a Generation Ship), humans could colonize the known Universe.

But of course, there are downsides to this imaginative proposal. During such a long voyage, multiple generations of people will be born and raised inside a closed environment. This could lead to all kinds of biological issues or mutations that we simply can't foresee. But according to a new study by a team of linguistics professors, there's something else that will be subject to mutation during such a voyage - language itself!

This study, " Language Development During Interstellar Travel," appeared in the April issue of *Acta Futura*, the journal of the European Space Agency's Advanced Concepts Team. The team consisted of Andrew McKenzie, an associate professor of linguistics at the University of Kansas; and Jeffrey Punske, an assistant professor of linguistics at Southern Illinois University.

In this study, McKenzie and Punske discuss how languages evolve over time whenever communities grow isolated from one another. This would certainly be the case in the event of a long interstellar voyage and/or as a result of interplanetary colonization. Eventually, this could mean that the language of the colonists would be unintelligible to the people of Earth, should they meet up again later.

For those who took English at the senior or college level, the story of Caxton's "eggys" ought to be a familiar one. In the preface to his 1490 translation of Virgil's Aeneid (Eneydos) into Middle English, he tells a story of a group of merchants who are traveling down the Thames toward Holland. Due to poor winds, they are forced to dock in the county of Kent, just 80 km (50 mi) downriver and look for something to eat:

*"And one of them named Sheffield, a merchant, came into a house and asked for meat and, specifically, he asked for eggs ("eggys"). And the good wife answered that she could speak no French. And the merchant got angry for he could not speak French either, but he wanted eggs and she could not understand him. And then at last another person said that he wanted ‘eyren’. Then the good woman said that she understood him well*."

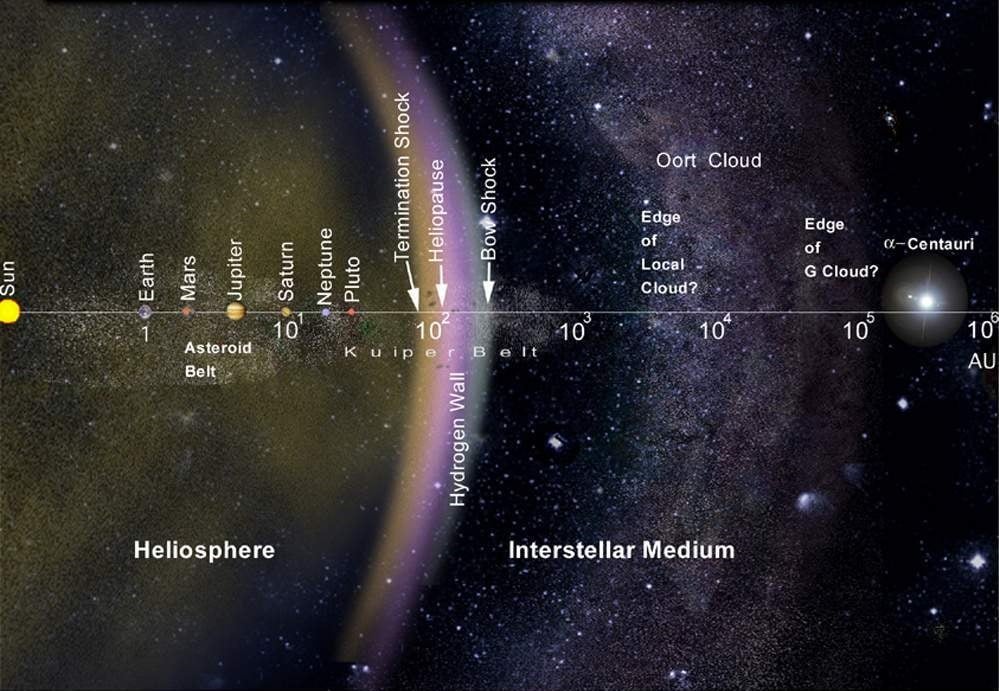

This story illustrates how people in 15th century England could travel within the same country and experience a language barrier. Well, multiply that to 4.25 light-years to the nearest star system and you can begin to see how language could be a major complication when it comes to interstellar travel.

To illustrate, McKenzie and Punske use examples of different language families on Earth and how new languages emerged due to distance and time. They then extrapolated how this same process would occur over the course of 10 generations or more of interstellar/interplanetary travel. As McKenzie explained in a UK press release:

"If you're on this vessel for 10 generations, new concepts will emerge, new social issues will come up, and people will create ways of talking about them, and these will become the vocabulary particular to the ship. People on Earth might never know about these words, unless there's a reason to tell them. " And the further away you get, the less you're going to talk to people back home. Generations pass, and there's no one really back home to talk to. And there's not much you want to tell them, because they'll only find out years later, and then you'll hear back from them years after that."

An example they use is the case of Polynesian sailors who populated the South Pacific islands between 3,000 and 1,000 BCE. Though the roots of these sailors are traced to Taiwan (ca. 6000 BCE) this process of expansion led to the development of entirely new cultures by the 1st millennium BCE. The Polynesian languages that emerged bore little resemblance to the ancient Austronesia language (aka. "Formosan") of their ancestors.

Similarly, the authors cite language changes that take place within the same language community over time, using the example of "uptalk." Also known as "High Rising Terminal," this phenomenon involves statements ending with a rise in intonation. While it is often mistaken for a question by those who are unfamiliar with it, the convention is actually intended to indicate politeness or inclusion.

As the authors note, "uptalk" has only been observed in the English language within the past 40 years and its origins are unclear. Nevertheless, the spread of it has been noted, particularly by members of the Baby Boomer generation that use it today, but did not in their youth. Another issue they identify is sign language, which will require adaptation from the crew since some crewmembers will be born hearing impaired.

Without someone keeping track of changes and trying to maintain grammatical standards, linguistic divergence will be inevitable. But as they note, that might be irrelevant, since language on Earth is going to change during that same time. "So they may well be communicating like we'd be using Latin — communicating with this version of the language nobody uses," said McKenzie.

Last, but not least, they address what will happen when subsequent ships from Earth reach the colonized planets and meet the locals. Without some means of preparation (like communication with the colony before they reach it), new waves of immigrants will encounter a language barrier and could find themselves being discriminated against.

Because of this, they recommend that any future interplanetary or interstellar missions include linguists or people who are trained in what to expect - translation software ain't gonna' cut it! They further recommend that additional studies of likely language changes aboard interstellar spacecraft be conducted, so people know what to expect in advance. Or as they conclude in their study:

"Given the certainty that these issues will arise in scenarios such as these, and the uncertainty of exactly how they will progress, we strongly suggest that any crew exhibit strong levels of metalinguistic training in addition to simply knowing the required languages. There will be need for an informed linguistic policy on board that can be maintained without referring back to Earth-based regulations. "

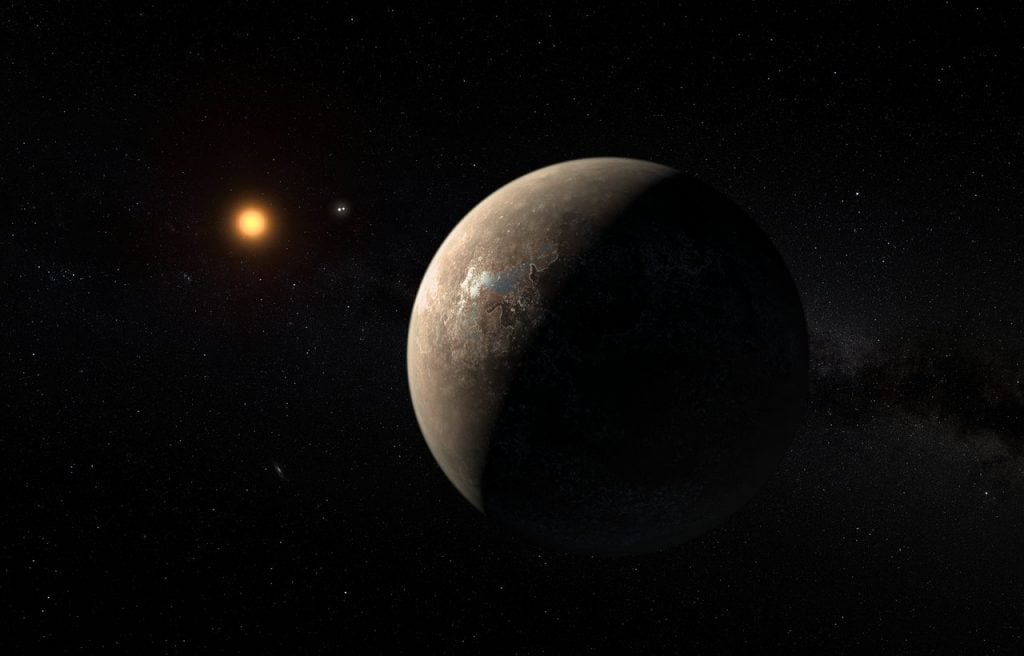

Just for fun, let's see what kinds of linguistic changes could take place. For starters, let's assume that a generation ship does take a full ten generations to reach its destination - in this case, Proxima b. Ten more generations pass before the next ship arrives, bringing people from Earth who still speak modern English.

Using the language evolution-simulator Onset, and an English-IPA translator, we can get a small taste of how a simple English-language greeting, and a common request (if you're in a 50s sci-fi B movie), would change over twenty generations:

"Helluhuh fret, goot tu'uh be'yat yu.Took be'ye to'o u'ul ley'eru, pley'yaz."

As you can see "Hello friend, good to meet you. Take me to your leader, please" comes out a little different after twenty generations of separation. How about something more complicated, but no less familiar? Here's a famous speech that fans of space exploration and history should recognize. After twenty years of interstellar travel, here's how that speech would sound:

"Wu'eh cho'oz to'o go to'o too Bo'od! Wu'eh cho'oz to'o go to'o too Bood id teez dey'ich udh do'oh tey'e de uttur teedgz, dot biga'ozz tey'e ar ey'ery'eh, boot biga'ozz tey'e ar hard; biga'ozz tat goal wool surve to'o olgoodiez uhd bez'hur too bezt oov uhur eluree'iaz uhd skeelz, uhd biga'ozz tat chaludi iz wuhd tat wu'e ahr wooleet to'oh igsept, wuhd wu'e ahr udu'illid to'o postbode, ohd wuhd wu'e iddet to'o wud."

Can you guess what speech that is? Let us known in the comments below! Keep in mind, this is just a basic simulation of how the English language might change for a group of colonists, never mind people here on Earth. And when you take time to consider all of the spoken language and dialects spoke today, and that any combination of these will be brought with the colonists to the stars, you can see how confounding it all could be!

There is a reason why the myth of the Tower of Babel remains embedded in our collective unconscious. Language barriers have always been a hurdle for human interaction, especially where long stretches of time and space are concerned. So if humanity plans to "go interstellar" (or interplanetary), we'll be taking that hurdle to a whole new level!

In the meantime, you can check out several other articles we've done on the subject of generations ships, how big they would have to be, and the minimum number of crew they would need.

Further Reading: University of Kansas*, Acta Futura*

Universe Today

Universe Today