Betelgeuse, the tenth brightest star in the night sky and the second brightest in the constellation Orion, has been behaving a little oddly lately. Beginning in December of 2019, researchers from Villanova University noticed the red supergiant was dimming noticeably. This trend continued into the new year, with Betelgeuse dimming throughout January and February of 2020. eventually losing two-thirds of its brilliance.

From this point onward, Betelgeuse began to brighten again and returned to its typical visual brightness by April. And now, the massive star dimming once again, and ahead of schedule. In response, an international team of researchers recently conducted a study where they theorized that this pattern might be the result of Betelgeuse " sneezing " out dense clouds of hot gas which then cooled.

The study that describes their observations via The Astronomer's Telegram and their full results appeared in *The Astrophysical Journal*. The team was led by Andrea K. Dupree, the associate director of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), the National Solar Observatory, Villanova University, the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam, and numerous universities and research institutes.

As a variable star, Betelgeuse has been known to go through periods of dimming and brightening that last about 420 days. However, the timing and extent to which the star was diminishing in brightness since 2019 seemed highly unusual. Explanations for why it was behaving this way included the possibility that Betelgeuse was about to go supernova, that it was creating clouds of dust, or because of massive stars spots.

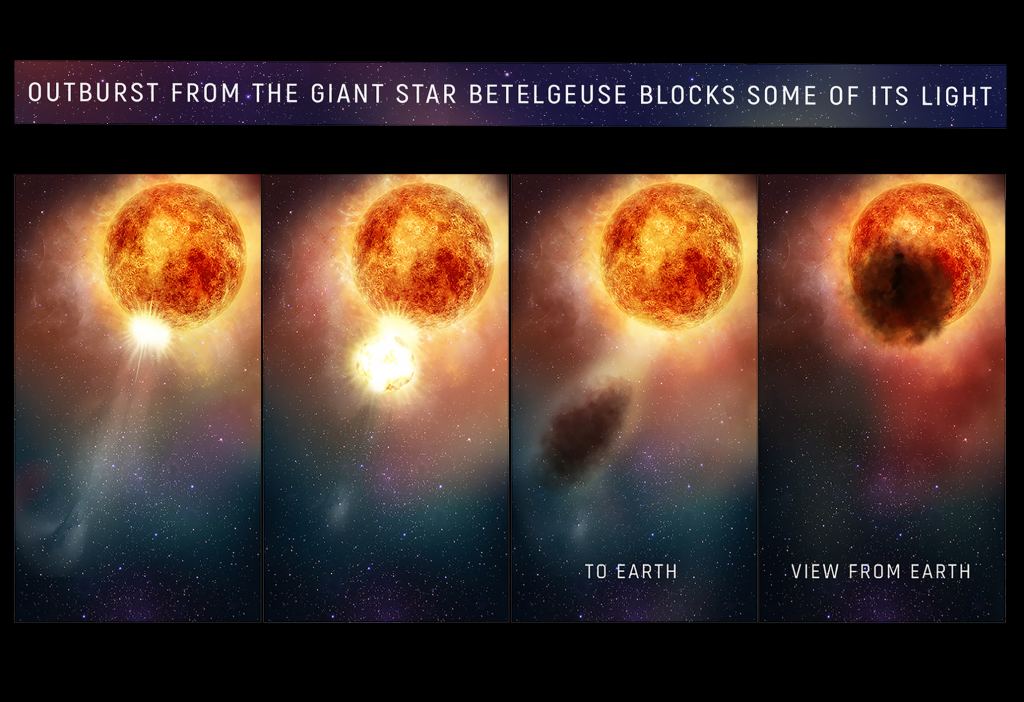

To this, the team led by Dupree offers another explanation: the dimming was caused by the ejection of hot dense clouds of plasma that temporarily obscured our view of the star. This was based in part on observations conducted between October and November 2019 by the Hubble Space Telescope, just a month before ground-based observatories began to notice dimming in the star's southern hemisphere.

These observations noted hot material moving outward through the star's extended atmosphere at over 320,000 km (200,000 mi) per hour. From this point onward, Hubble observations conducted in the ultraviolet wavelength provided a timeline that researchers were able to follow backward, allowing them to pinpoint the exact moment when the dimming began. As Dupree explained in a recent CfA press statement:

"With Hubble, we had previously observed hot convection cells on the surface of Betelgeuse and in the fall of 2019 we discovered a large amount of dense hot gas moving outwards through Betelgeuse’s extended atmosphere. We think this gas cooled down millions of miles outside the star to form the dust that blocked the southern part of the star imaged in January and February. The material was two to four times more luminous than the star's normal brightness. And then, about a month later the south part of Betelgeuse dimmed conspicuously as the star grew fainter. We think it possible that a dark cloud resulted from the outflow that Hubble detected. Only Hubble gives us this evidence that led up to the dimming."

Another interesting thing revealed by Hubble was where the plasma ejections it observed were coming from. Rather than being ejected from the star's rotational poles - as current stellar models predict- it appeared to be coming from near the equator around the southern hemisphere. In addition to defying conventional wisdom about how stars behave, this activity is also abnormal for Betelgeuse itself.

You see, while Betelgeuse is losing mass at a rate of 30 million times that of the Sun, the recent ejection constituted a loss that was about twice the normal amount of material. Said Dupree:

"All stars are losing material to the interstellar medium, and we don't know how this material is lost. Is it a smooth wind blowing all the time? Or does it come in fits and starts? Perhaps with an event such as we discovered on Betelgeuse? We know that other hotter luminous stars lose material and it quickly turns to dust making the star appear much fainter. But in over a century-and-a-half, this has not happened to Betelgeuse. It’s very unique."

The team also took into account observations conducted by the STELLAr Activity Observatory (STELLA) in Spain, which relies on two 1.2 m (~4 ft) telescopes to combine high-resolution spectroscopy with wide-field images. When Betelgeuse moved into daylight and was no longer visible to Hubble or STELLA, researchers turned to NASA's Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory (STEREO) to monitor the supergiant's brightness.

What STELLA revealed was a rippling effect on Betelgeuse's face, apparently caused by the way the surface rose and fell during the star's pulsation cycle. This could have caused the ejected plasma to be propelled through the star's atmosphere. As Klaus G. Strassmeier, director of the Cosmic Magnetic Fields research branch at the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam and a co-author on the study, explained:

"We saw all the absorption lines in the spectrum blue shifted and knew that the star was expanding. When the dimming started, the blue shift became smaller and smaller and actually reverted to a redshift when the star was faintest. So we knew the dimming must have been related in one or another way to the expansion and contraction of the star’s photosphere, but it alone could not have caused such great dimming."

Meanwhile, STEREO observed Betelgeuse on five separate days between late June and early August 2020, measuring the star's brightness in comparison to other stars. This revealed something very surprising, which was that the star was unexpectedly dimming yet again! Since the previous dimming happened in February 2020 (and the star's 420 day cycle), this new period of dimming is over a year early.

Looking ahead, Dupree plans to observe Betelgeuse with STEREO again next year when the star will be at its brightest (aka. solar maximum) to see if there are any more unexpected outbursts. This information will go a long way towards determining why Betelgeuse has been experiencing the activity astronomers have seen and whether or not the star could be nearing a supernova.

But of course, it's important to note that since Betelgeuse is 725 light-years from Earth, the activity we are seeing today took place back in the year 1305 CE. So if an explosion is in the cards, it would have already happened and we are just waiting to get the memo. As Dupree concluded, there's still much we don't know about stellar behavior prior to a supernova:

"Betelgeuse is a bright star in our galaxy, near the end of its life that is likely to become a supernova. When the star became very faint in February 2020, this was the faintest that it had ever been since measurements began over 150 years ago. The dimming was obvious to everyone when looking at the constellation Orion; it was very weird, Betelgeuse was almost missing." "No one knows how a star behaves in the weeks before it explodes, and there were some ominous predictions that Betelgeuse was ready to become a supernova. Chances are, however, that it will not explode during our lifetime, but who knows?"

*Further Reading: CfA*

Universe Today

Universe Today