The behaviour of galaxies in the early Universe attracts a lot of attention from researchers. In fact, everything about the early Universe is under intense scientific scrutiny for obvious reasons. But unlike the Universe’s first stars, which have all died long ago, the galaxies we see around us—including our own—have been here since the early days.

Current scientific thinking says that in the early days of the Universe, the galaxies grew slowly, taking billions of years to become what they are now. But new observations show that might not be the case.

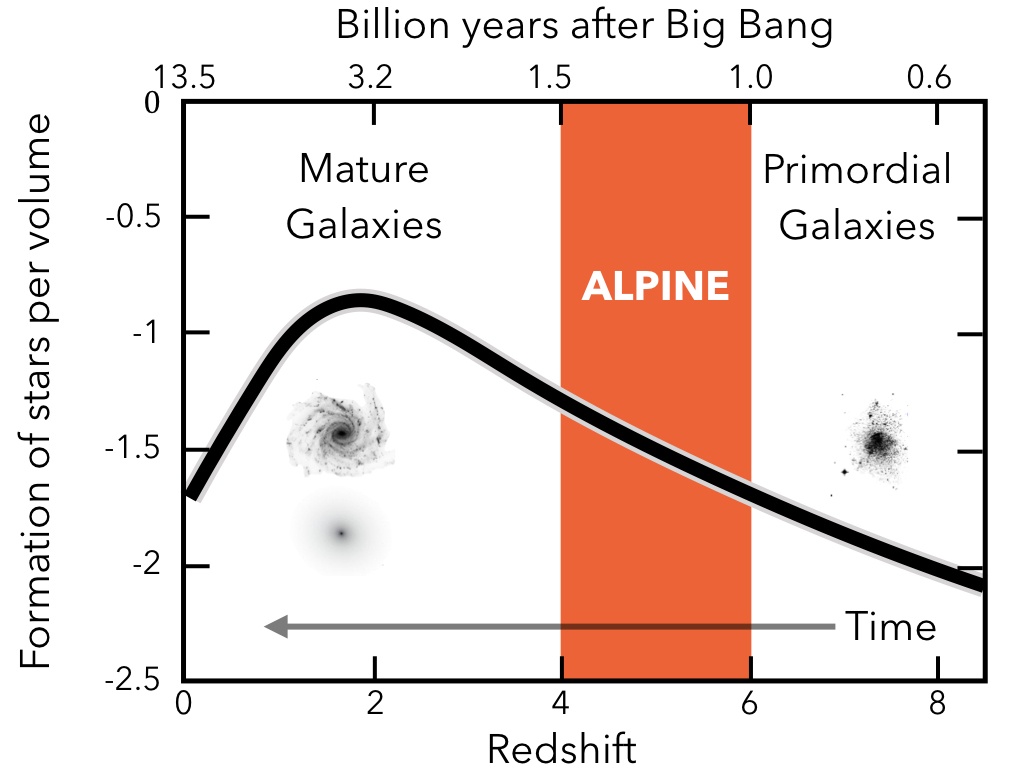

The new observations are from a survey called ALPINE (the ALMA Large Program to Investigate C+ at Early Times). ALPINE is a program that studies gas and dust properties of young galaxies during the early growth phase at redshifts z = 4-6.

“To our surprise, many of them were much more mature than we had expected.”

Andreas Faisst, IPAC at Caltech

The survey found that many galaxies experienced a growth spurt between 1 and 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang. During that growth spurt, galaxies acquired a significant amount of their stellar mass and dust. They also developed into the spiral galaxies that we see today and acquired heavy element content.

In the ALPINE survey, an international team of astronomers looked at 118 of these early galaxies that underwent growth spurts.

Andreas Faisst is one of the researchers involved in ALPINE. Faisst is a researcher at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center (IPAC) at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and is also the lead principal investigator for ALPINE in the USA. In a press release, he said, “To our surprise, many of them were much more mature than we had expected.”

The dust content heavy element in a galaxy is what differentiates young galaxies from mature galaxies. Only mature galaxies have higher amounts of dust and metals, because they’re a by-product of dying stars. Young galaxies haven’t been around long enough for generations of stars to die and create the dust and metals.

When researchers looked at the 118 young galaxies they were surprised to see so much dust and so much metallicity. Their presence indicated that there had already been more stellar activity than thought. “We didn’t expect to see so much dust and heavy elements in these distant galaxies,” said Faisst.

Daniel Schaerer of the University of Geneva is another scientist involved with ALPINE. “From previous studies, we understood that such young galaxies are dust-poor,” said Schaerer. “However, we find around 20 percent of the galaxies that assembled during this early epoch are already very dusty and a significant fraction of the ultraviolet light from newborn stars is already hidden by this dust,” he added.

Credit: B. Saxton NRAO/AUI/NSF, ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), ALPINE team.

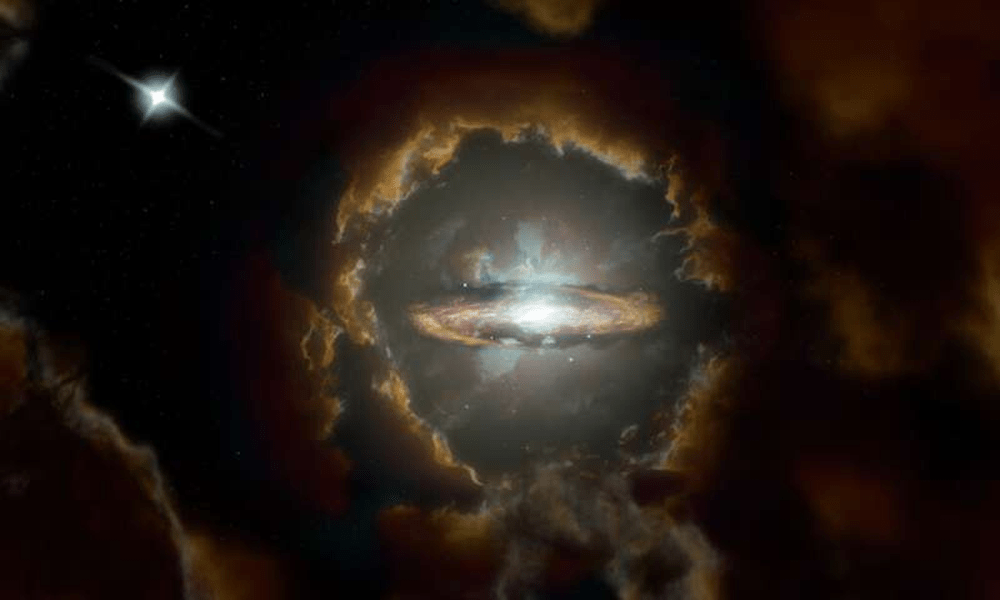

Another question about the early galaxies is when they established rotation, and how soon that affected their structure. Spiral galaxies like our own Milky Way rotate, and that creates the spiral structure. Many of the galaxies in the study showed signs of rotationally-supported disks and diverse structures.

This goes against expectations.

According to accepted thinking, the early galaxies should be more chaotic and messy. Frequent galactic collisions and mergers should have prevented so much structure from emerging at such a young Universal age. “We see many galaxies that are colliding, but we also see a number of them rotating in an orderly fashion with no signs of collisions,” said John Silverman of the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe in Japan.

Credit: B. Saxton NRAO/AUI/NSF, ESO, NASA/STScI; NAOJ/Subaru

Astronomers have observed distant galaxies from this time period before, like MAMBO-9 and the Wolfe Disk. MAMBO-9 is very dusty, and the Wolfe Disk has a rotating disk, so they were clues that galaxies could mature faster than thought. But they may have been outliers, and it took a larger survey like ALPINE to give researchers a clearer picture.

But even though ALPINE has identified a handful of these early-bloomers, astronomers still don’t know how they grew up so fast and why some of them have rotating disks at such a young age.

ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimetre Array) played a huge role in this work. It’s an extremely powerful radio telescope, and that’s what’s needed to see these distant galaxies. While many of these galaxies are basically invisible in optical and infrared light, they can shine quite brightly in millimetre and submillimetre radiation. Whereas optical and infrared can’t pierce the dusty regions where stars form, or the motion of gas in these galaxies, ALMA can. In fact, optical and infrared telescopes sometimes miss entire galaxies.

“With ALMA we discovered a few distant galaxies for the first time. We call these Hubble-dark as they could not be detected even with the Hubble telescope,” said Lin Yan of Caltech.

The team intends to keep using ALMA’s strength to try and understand why these young galaxies are so mature. While ALPINE was a survey that used 70 hours of observing time, they’d like to use ALMA to observe individual galaxies for longer periods of time. “We want to see exactly where the dust is and how the gas moves around. We also want to compare the dusty galaxies to others at the same distance and figure out if there might be something special about their environments,” added Paolo Cassata of the University of Padua in Italy, formerly at the Universidad de Valparaíso in Chile.

ALMA can’t do this work alone, of course. ALPINE is the largest survey of this type, where multiple telescopes at different wavelengths were used to study galaxies in the early Universe. A whole fleet of optical ‘scopes were used, including the Hubble, Keck, and VLT. And Spitzer’s infrared capabilities were used, too. It’s impossible to understand the history of distant galaxies without observations across multiple wavelengths.

“Such a large and complex survey is only possible thanks to the collaboration between multiple institutes across the globe,” said Matthieu Béthermin of the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille in France.

Thanks for such an informative article on a topic that should lie right at the science edge – early galaxy and star formation history!

The early maturity correlates well with the Ligo survey on black hole formation which – from the other side of the star formation peak though – find a correlation between black hole formation and star formation rate. So perhaps growth of supermassive black holes, which presumably forces the peak by tending to form active galaxy nuclei, is also early matured.

[Herein lies another mystery to me: the relatively non-active Milky Way, give or take some Fermi lobes and satellite/star stream evidence of earlier activity, has a slow rotating supermassive SagA* black hole versus the at least 4 times faster M87* rotation as seen in the black hole shadow image. So here too there is the larger range of diversity that we see in galaxies and individual planetary systems.

Presumably it is harder to form jets with a slow rotator. But why is it slower?]